The rise of Beppe Grillo and the political resilience of Silvio Berlusconi were two of the main stories to emerge from last week’s Italian election. As Duncan McDonnell and Giuliano Bobba argue, however, the Grillo and Berlusconi headlines should not disguise the stark position of the Italian centre-left. The Partito Democratico has now lost over three million voters in five years.

The rise of Beppe Grillo and the political resilience of Silvio Berlusconi were two of the main stories to emerge from last week’s Italian election. As Duncan McDonnell and Giuliano Bobba argue, however, the Grillo and Berlusconi headlines should not disguise the stark position of the Italian centre-left. The Partito Democratico has now lost over three million voters in five years.

Devon Loch in 1956, Greg Norman over several decades, AC Milan in 2005 and Pierluigi Bersani in 2013. Spot the connection. Although we wrote here a few weeks ago that the Partito Democratico (PD – Democratic Party) was stalling in the election campaign, we didn’t think we’d find ourselves including Bersani in a list of famous chokers – those who have thrown away leads which looked unassailable. Nor did any of Italy’s pollsters who were predicting a gap of around five points between Bersani’s and Silvio Berlusconi’s coalitions. This was less than the 10-15 points which had separated them in previous months, but it was still considered enough to ensure that, whether alone or in a post-election coalition with Mario Monti’s centrist group, the PD-SEL alliance would be taking its place in government and Bersani would be prime minister.

Whether that will happen is of course now very much in the balance. Rather than speculating about what the future holds, however, here we want to reflect on what actually happened in the election – something which much of the media coverage, with its focus on Berlusconi and Beppe Grillo’s Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S – Five-Star Movement), has not done particularly well. As we see it, there are four main points of interest regarding the centre-left:

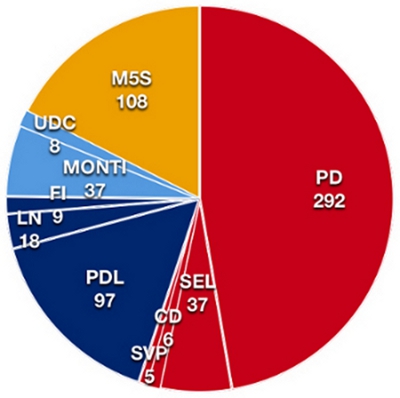

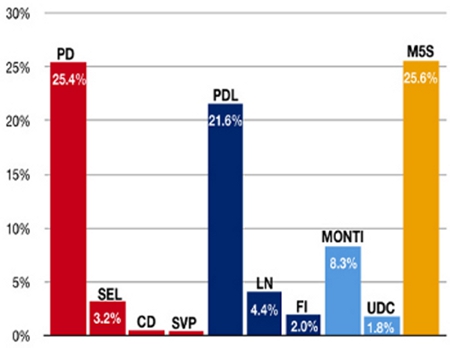

1) In contrast to what we had thought for at least the past two years, the PD is not Italy’s undisputed leading party. The centre-left coalition with 29.5% finished 0.3 percentage points ahead of the centre-right in the Chamber of Deputies vote, thus claiming the majority seat bonus (see figure 1). However, as we can see from figure 2, the PD was surpassed as the top individual party by the M5S.

Figure 1: Party Seats in the Chamber of Deputies

Note: All data is based on that provided by the Ministero dell’Interno. It does not include the ‘Italians abroad’ and Valle D’Aosta constituencies.

Figure 2: Party vote shares in the Chamber of Deputies election

Note: As above.

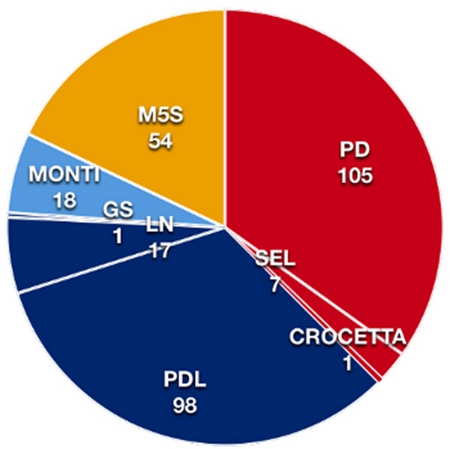

In the Senate (for which voters must be 25 or over), the PD was the top party and its coalition placed first. However, because of Italy’s bizarre 2005 electoral law which awards the seat bonus in the Senate according to how coalitions fare in individual regions rather than nationally (as is the case for the Chamber), the centre-left failed to secure a majority and Monti’s coalition did so poorly that an alliance with it would still not be enough to form a viable government.

Figure 3: Party seats in the Senate

Note: As above

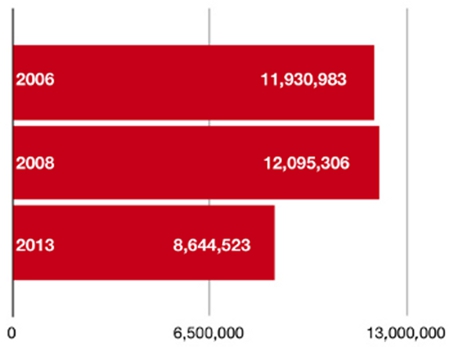

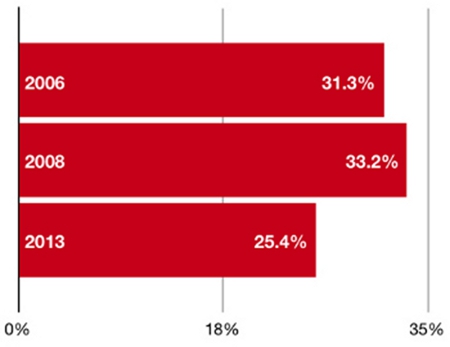

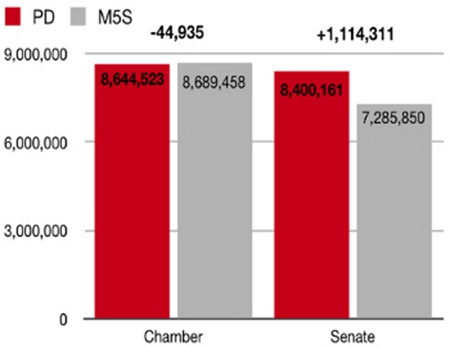

2) In terms of both vote share and the actual number of people who voted for it, the PD performed worse than in the last two general elections. As we can see from Figures 4 and 5 below, the decline on its 2008 result – especially in absolute numbers – is very significant. The PD has lost over three million voters in five years.

Figure 4: PD votes (absolute numbers) in the 2006, 2008 and 2013 general elections

Note: For 2006, we have calculated the PD’s vote as that of the Ulivo. Figures relate only to the Chamber of Deputies. Data does not include the ‘Italians abroad’ and Valle D’Aosta constituencies.

Figure 5: PD vote share in 2006, 2008 and 2013 general elections

Note: As above

3) It is misleading to frame the result as somehow a Berlusconi victory over the centre-left. There has been much written to this effect in the media. A New York Times editorial even asserted that ‘Berlusconi’s slate won the largest number of Senate seats’ – which is just plain wrong. Those claiming a Berlusconi ‘success’ should also consider that his PDL lost over six million voters and circa 16 percentage points compared to its 2008 result. And that the centre-left and the PD finished ahead of the centre-right and the PDL respectively in both the Chamber of Deputies and Senate elections.

4) The PD, as we have seen above, lost in the Chamber election to the M5S which enjoyed the most successful debut general election in recent decades in Western Europe. In terms of who voted for the M5S, there are two elements of concern for the PD. Firstly, according to an Istituto Cattaneo study in various cities, a significant share of M5S voters in 2013 had voted for the PD in 2008 (with 58% in Florence the top figure). Second, the M5S is clearly more attractive to younger voters than the PD. We can see this if we look at the differences in the votes for the two parties in the Chamber of Deputies (for which voters must 18 or over) and the Senate (for which voters must be 25 or over). While of course it is possible that some over-25s voted differently in the Chamber election than they did in the Senate one, the gap is such that it is logical to assume that the M5S did much better than the PD among 18-24 year olds.

Figure 6: PD and M5S votes in the 2013 general election

Note: all data is based on that provided by the Ministero dell’Interno. It does not include the ‘Italians abroad’ and Valle D’Aosta constituencies.

Finally, three other brief general reflections: First, although it has anomalous elements, what seems to have passed commentators by is the fact that, in one sense, this election is entirely in line with those elsewhere: the parties which had supported Monti’s government – the PD, PDL and UDC – all lost votes compared to 2008. We have seen this happen to governing parties in almost all general elections in Western Europe during the crisis.

Second, rather than labelling the M5S result as a ‘protest vote’, the centre-left would do well to remember that many of the movement’s themes (anti-corruption laws, political system reform, the environment, universal unemployment benefit, local referendums on large public works) are dear to their own supporters (and potential supporters) too.

Last, but not least, amid all the confusion of the past week, we have been provided with one salutary reminder: Italian democracy’s fate is not solely in the hand of the markets, the European Union or editorial writers of international newspapers. After the suspension of party government in Italy for over a year, the citizens have finally spoken. What they have said obviously doesn’t please The Economist or Germany’s Social Democrat leader Peer Steinbrueck, but the Italian centre-left would do well now to listen to those actually in Italy. They might just learn something that would help them avoid choking next time.

This is a contribution to Policy Network’s work on Liberal democracy under stress.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/WsK5vk

_______________________________

About the Authors

Duncan McDonnell – European University Institute, Florence

Duncan McDonnell – European University Institute, Florence

Duncan McDonnell is Marie Curie Fellow in the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the European University Institute in Florence. He is the co-editor of Twenty-First Century Populism (Palgrave, 2008), the 2012 ‘Politica in Italia/Italian Politics’ yearbook and has recently published on the Lega Nord, Outsider Parties and Silvio Berlusconi’s personal parties. He is currently working with Daniele Albertazzi on a book entitled ‘Populists in Power’ which will be published by Routledge. He tweets at @duncanmcdonnell.

Giuliano Bobba – University of Turin

Giuliano Bobba – University of Turin

Giuliano Bobba is a Lecturer at the Department of Culture, Politics and Society in the Universityof Turin. His research interests include: political communication and election campaigns; the evolution of political parties and leadership in Western democracies; the European integration process and the development of a European public sphere. He has published in particular on media and politics in Italy and France. He is the manager of the Political Communication Observatory website in Turin.

1 Comments