There is growing recognition that migrants to Europe can act as agents of development for their countries of origin, and that this is something that should be encouraged through engagement with diaspora and migrant organisations. Using nine examples of good practice from across Europe, Nadja Schuster and Marlene Keusch argue for more coherence between migration and development policies. They write that the EU could do more to harness migrants’ development potential, and should move to a more human rights based approach to migration, and away from more restrictive migration policies.

There is growing recognition that migrants to Europe can act as agents of development for their countries of origin, and that this is something that should be encouraged through engagement with diaspora and migrant organisations. Using nine examples of good practice from across Europe, Nadja Schuster and Marlene Keusch argue for more coherence between migration and development policies. They write that the EU could do more to harness migrants’ development potential, and should move to a more human rights based approach to migration, and away from more restrictive migration policies.

Migration holds great development potential. The historic pessimistic view of the links between migration and development has now shifted to a more positive one, since the drastic increase in remittances between rich and developing countries in recent decades. The recognition of migrants as agents of development and their valuable contribution as citizens to both their origin and destination countries is steadily increasing. Policy makers and politicians are becoming more and more interested in the activities of diaspora and migrant organisations, recognising their potential for poverty reduction, development and economic growth.

Sharing information on good practices in migration policy increases the effectiveness and impact of new programmes, and avoids duplication. We can learn from countries like France, Germany and the Netherlands who have actively supported migrant organisation initiatives through specific policies and programmes aimed towards building synergies between different stakeholders with the same goal: implementing the potential of migration for development.

Our Study of European Good Practice Examples responds to the need to understand and improve the migration and development domain that links Europe with migrant-sending countries. In our case study, we analysed nine good practice examples implemented by governmental, non-governmental and diaspora-led organisations. What they have in common is the engagement of diasporas building upon the cooperation of different actors.

Despite migration’s potential, many EU countries (and not only those governed by populist and right-wing parties) believe that development in the countries of origin can reduce migration from the South to the North. This shows that the underlying causes of migration have not yet been analysed and understood. On the one hand, harsh or unsatisfactory living and working conditions can indeed be a motivation to migrate. On the other, higher levels of development can also trigger the wish to migrate. In addition, willingness to migrate is determined by hopes and ambitions of persons and small groups, such as families and households.

The driving factors behind migration are many, but empirical and theoretical evidence shows that economic and human development increases people’s capabilities and aspirations and therefore leads to an increase in emigration, at least in the short to medium term. At the same time, demand for both highly skilled and unskilled migrant workers in Europe is likely to persist. In light of this, migration appears to be here to stay, and aid or diaspora engagement programs are no short-cut ‘solution’ to control migration flows. Neither will restrictive immigration policies nor the militarization of external border controls by the EU curb immigration from Africa, Asia and Latin America. On the contrary, they have led to an increase in risky, costly and irregular migration and have paradoxically stimulated permanent settlement.

Before we scrutinised good practice examples, we approached the question of the coherence of migration policy and development objectives by looking at actual EU policies on migration and development. Although positive views on migration are slowly increasing, what prevails in the EU is a restrictive approach to migration with the aim of realising the EU’s unilateral economic objectives. Border management and combating illegal migration, rather than a human rights based approach, are high on the political agenda. The EU does not understand the concept of circular migration as the right of free movement between two or more countries but rather as a likely conditional back and forth movement or restricted return migration. What is more, populist and right-wing parties have connected security and criminality to migration, thereby nourishing the negative public image of migrants that is supported by the mainstream media.

Based on an extensive review of printed and online literature, interviews with experts and the experiences of partners of the Vienna Institute for International Dialogue, the good practice examples in our study were selected according to the following criteria: positive views of migration, migrants as key players and/or main beneficiaries, quality of cooperation, collective activities, accessibility and availability of information. With regard to sustainability, an additional decisive factor that became prevalent during the research is the spill over effect of the initiative into regular development cooperation.

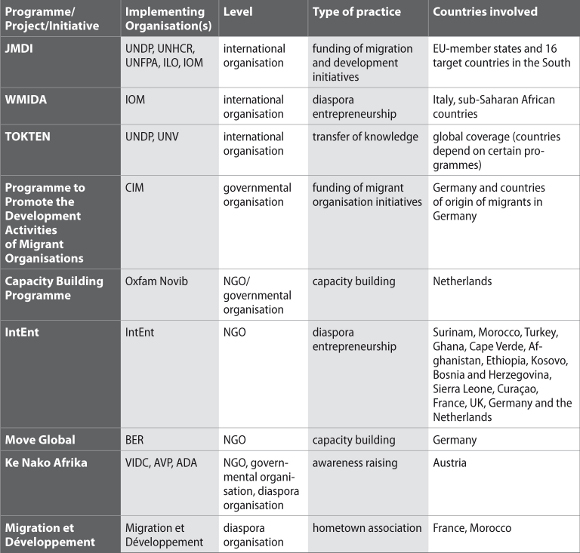

Figure 1 below presents the nine selected good practice examples of migration and development initiatives. The activities of the programmes/projects range from awareness raising and the facilitation of business investment start-ups to the promotion of knowledge transfer, capacity building, financial support and hometown associations.

Figure 1 – Good practice examples of migration and development initiatives

An overall lack of evaluation in the migration and development domain makes it even more important to synthesise available information and collect lessons learned from successfully implemented and sometimes long-lasting initiatives. Moreover, examples can serve as a stimulus for policy-makers, officials, development organisations, diaspora organisations, and other actors.

We recommend for improved cooperation between governmental, non-governmental and diaspora organisations and for more coherence between migration and development policies.

For improved cooperation we recommend:

- Recognising diaspora organisations as development actors

- Mobilising development actors for diaspora engagement

- “Unpacking the diaspora”

- Equal partnership and ownership

- Open and broad definition of development

- Awareness raising and knowledge transfer

- Capacity building and consultation for diaspora organisations

- Promoting evaluation

In a second step, for more coherence between migration and development policies we recommend:

- Human rights protection of migrants

- Authorisation of dual citizenship

- Inclusion of migrants in policymaking

- Shift from a project to a process approach

- Promoting research and development education

Some of these recommendations might not seem new, however, evidence from our experience and that of our partners shows that they have not yet been put into practice in most of the EU member countries.

Fundamental structural changes in the migration and development field are needed as well as behaviour changes for key stakeholders. Mutual trust as well as the recognition of current diaspora activities is indispensable for an equal and sustainable cooperation between diaspora, governmental and non-governmental organisations. In order to fully implement the development potential of diasporas and to promote their transnational participation, a human-rights based approach and freedom of movement instead of restrictive migration policies is fundamental. We encourage European countries to promote socioeconomic mobility of migrants through the establishment of legal possibilities for highly and low qualified migrants as well as through an active integration policy.

This study was undertaken within CoMiDe (www.comide.net), the Initiative for Migration and Development. The VIDC (Vienna Institute for International Dialogue and Cooperation) is the lead agency in this EU-funded project. Partners are the Peace Institute – Institute for Contemporary Social and Political Studies (Slovenia), COSPE – Cooperazione per lo Sviluppo dei Paesi Emergenti (Italy), Society Development Institute (Slovakia) and Südwind Agentur (Austria).

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/150oi12

__________________________________________

Nadja Schuster – Vienna Institute for International Dialogue and Cooperation (VIDC)

Nadja Schuster – Vienna Institute for International Dialogue and Cooperation (VIDC)

Nadja Schuster studied Sociology at the University of Vienna and Development Management and Evaluation at the University of Antwerp. Since 2011 she has worked with the VIDC. Besides migration and development her areas of expertise are policy coherence for development, trafficking in human beings and gender-based violence in post-conflict societies.

–

Marlene Keusch – University of Vienna

Marlene Keusch – University of Vienna

Marlene Keusch studies International Development and Geography at the University of Vienna. Currently she is writing her master thesis concerning “Diaspora organizations as development actors”, for which she conducts a research in Austria.

1 Comments