How do the political attitudes of parents influence those of their children? As Elias Dinas notes, a common assumption is that children from more politically engaged families are more likely to retain their parents’ political views. Taking issue with this perspective, he finds evidence that while young people from politicised homes may be more likely to acquire an initial partisan orientation from their parents, they are also more likely to abandon that preference as they enter adulthood and experience politics for themselves.

How do the political attitudes of parents influence those of their children? As Elias Dinas notes, a common assumption is that children from more politically engaged families are more likely to retain their parents’ political views. Taking issue with this perspective, he finds evidence that while young people from politicised homes may be more likely to acquire an initial partisan orientation from their parents, they are also more likely to abandon that preference as they enter adulthood and experience politics for themselves.

How do we end up supporting a specific political party? Why do some people in the UK, for instance, call themselves Labour or Conservative supporters, whereas others fail to identify with any individual party at all? One of the most oft-cited explanations alludes to the role of parents. Through family socialisation, young individuals get to know about the `goodies’ and the `baddies’ of the political world. Accordingly, they form their partisan preferences before they develop a sophisticated understanding of politics. These attachments may not be strongly felt, but children rarely declare a party identification with the main rival of the party to which parents are loyal.

Research in social psychology confirms this view. In what probably constitutes the most influential critique to the long-standing notion that children’s personalities are shaped by their parents, Judith Harris suggests that what matters for the formation of an adult is genes and peers. Still, she acknowledges that her `nurture thesis’ does not hold for the development of political preferences. During childhood, political attitudes are not defining features linking peer groups. Thus, political views acquired at home are not undermined by conformity within these groups. Eventually, however, adolescents become adults and they leave their parents’ home. For some, the partisan affiliation expressed in childhood persists and for others it does not. What explains this variation?

If one pictures parental influence as a form of partisan legacy, we are led to conclude that the more vivid parental politicisation has been during childhood, the more likely its footprints are to persist during adulthood. Parents who provide unambiguous partisan cues are those parents who talk more about politics. These parents, according to the established wisdom, should then be more successful in transmitting an enduring partisanship to their offspring. It turns out, however, that this logic is partially wrong. The reason is that it considers the strength of the initial socialisation, but neglects the strength of the change-inducing circumstances individuals confront later in life.

Once leaving their parental home, young adults frequently encounter new political stimuli, some of which may contradict their parental partisan lessons. Political learning may be prompted by mass media communications or through experiences in college, in the workplace, and in newly formed social networks and families. Although the partisan direction of these cues will depend on the time period and the specific social locations of individuals, the magnitude of their influence on young people’s partisan outlooks should vary according to the individual’s latent predisposition to receive such cues, which in turn will depend on their level of political involvement. Although selective exposure will shape some information flows, others can be thought of as operating exogenously. People do not tend to opt for colleges or jobs on partisan grounds. And while sorting is strong in the selection of spouses, it is much weaker when it comes to the people a young person interacts with in college or in the work environment. Exposure to political discussion in such contexts may lead to instances in which prior views are challenged.

Here again, political socialisation enters in, since a person’s attentiveness to public affairs is shaped by experiences during childhood and adolescence. Although not the only agent of socialisation, the family plays an important role in inspiring the child to take an interest in the political world. Politically interested young adults are likely to have grown up in politicised families. An adolescent acquainted with political discussions within the family will probably continue to talk about politics in their new social contexts. A person whose early socialisation promoted knowledge of and interest in politics will likely continue to be attentive and interested as they move through their adult years. This contact will bring them closer to external influences that might induce them to revise their political worldview.

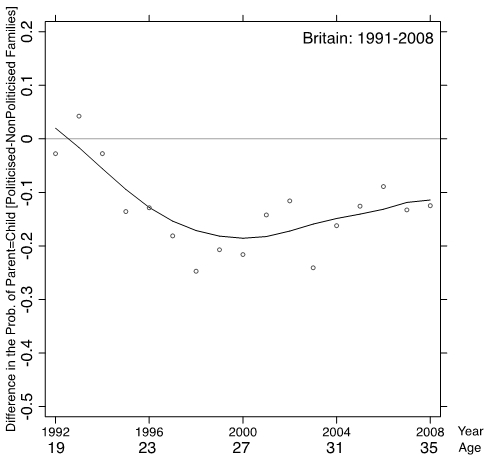

Political engagement on the part of parents, thus, plays a dual role in the political socialisation of the young. It boosts the intensity of pre-adult political learning, strengthening the transmission of political attitudes from parent to child. It also makes children more politically engaged themselves. Taken together, a seemingly counter-intuitive pattern arises. Young people from politicised homes may be more likely to acquire an initial partisan orientation from their parents, but they are also more likely to abandon that preference as they enter adulthood and experience politics for themselves. Evidence from the US and Britain confirms this perspective, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Parent-child political convergence for politicised and non-politicised families in the UK (1991-2008)

Notes: Each dot represents the average difference in the probability of party similarity between parent and child between children from more politicised families and children from less politicised families. The black solid curve summarises the pattern, showing how the passage through early adulthood is shaped by decreasing levels of convergence among offspring from more politicised homes. The analysis is based on the British Household Panel Study.

The evidence shows that young Americans and Britons from highly politicised homes are more likely to deviate from their parents’ partisan preferences. Moreover, the evidence helps to shed light on the mechanisms. A typical context within which many young adults find themselves is the university – a left-leaning institution. Consistent with the argument presented here, it turns out that offspring from right-wing politicised homes are more likely to shift towards a more left-wing direction than children that stem from less politicised right-wing families. Furthermore, when an important political event takes place, be it a war or a scandal, young adults from more politically active families are more likely to update their partisan preferences accordingly. The evidence shows that parent-child divergence is not confined to instances in which the political context prompts young people to develop more liberal stances. For instance, during the 1960s, the civil-rights movement led the American South away from the Democratic party. Consistent with the hypothesis advanced here, it was the young Southerners growing up in politically engaged homes who primarily drove the shift away from the Democrats.

Apart from highlighting the multi-dimensional role of family socialisation, the overall results also shed light on the origins of political change over time. Period forces give room to the formation of generational units only when they are infiltrated through one’s own active involvement. New political climates are only a necessary condition for political change. The sufficient condition is political engagement, at least in part originating in family socialisation. Thus, if knowledge of parental partisanship is important in explaining continuity, knowledge of parental politicisation may be more vital for our understanding of partisan and attitudinal change.

For a longer discussion of the topic covered in this article see: Dinas, Elias (2013) Why Does the Apple Fall Far from the Tree? How Early Political Socialization Prompts Parent-Child Dissimilarity. British Journal of Political Science.

This article was cross-posted simultaneously on the University of Nottingham’s Ballots & Bullets site.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/12xPXDo

_________________________________

About the author

Elias Dinas – University of Nottingham

Elias Dinas – University of Nottingham

Elias Dinas is a Lecturer in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Nottingham. His main research interests are political socialisation, and the formation and crystallisation of political attitudes and partisan identities.

Obvious, today my son is only thirteen year old, before he expresses his political views which may be opposed from my political views, the world political views will be already changing. Political analysts do not deviate from their political views publicly because they are identified through them, they make living out of them, while privately they may express different views