Strengthening civil society is often assumed to be a mechanism for promoting improved governance. Thilo Bodenstein assesses this perspective using comparative data on the strength of civil society across different regions. He finds that the single biggest factor leading to a strong civil society is the presence of high quality political institutions within a given country. Crucially, however, this effect only appears to operate in one direction: high quality political institutions help create a strong civil society, but a strong civil society alone is unlikely to lead to significant improvements in the quality of a country’s institutions.

Strengthening civil society is often assumed to be a mechanism for promoting improved governance. Thilo Bodenstein assesses this perspective using comparative data on the strength of civil society across different regions. He finds that the single biggest factor leading to a strong civil society is the presence of high quality political institutions within a given country. Crucially, however, this effect only appears to operate in one direction: high quality political institutions help create a strong civil society, but a strong civil society alone is unlikely to lead to significant improvements in the quality of a country’s institutions.

The flower revolutions and the recent Arab Spring that changed the political landscape in Eastern Europe and North Africa highlight the vital role a civil society plays in bringing about political change. Since its ‘rediscovery’ in the mid-1980s, civil society has been seen as a crucial factor for economic wellbeing, democratisation, and quality of democracy. The concept of civil society has also reached the political agenda of the European Union’s external and foreign aid policies. The EU’s Neighbourhood Policy explicitly mentions the promotion of civil society in the partner countries to support and strengthen democracy. In its foreign aid policy the EU recently published a document on how to engage with civil society. Similarly, many EU member states have identified civil society as a tool for achieving foreign policy goals. But this fresh emphasis on civil society rests on two assumptions – first, that we know what civil society is and second, that we know how to create a strong civil society.

Civil society is one of the social sciences’ more loosely defined concepts. The variety of definitions stretches from more classical notions such as membership of associations, to the current understanding of participation in political mass protest and the number of NGOs operating in a country. Only a few experts, however, would argue that any of these narrow definitions is a reliable measure of civil society across nations. To overcome the problems of fragmentary civil society definitions CIVICUS has developed a new Civil Society Index (CSI). The CSI breaks down the concept of civil society into four components: the structure of civil society (e.g. breadth and depth of citizen participation), the values of civil society (e.g. democratic practices and transparency within civil society organisations), the environment in which civil society operates (e.g. political context and legal environment) and the impact of civil society (e.g. influencing public policy). The approach brings together various operating definitions of civil society and makes the concept comparable across countries.

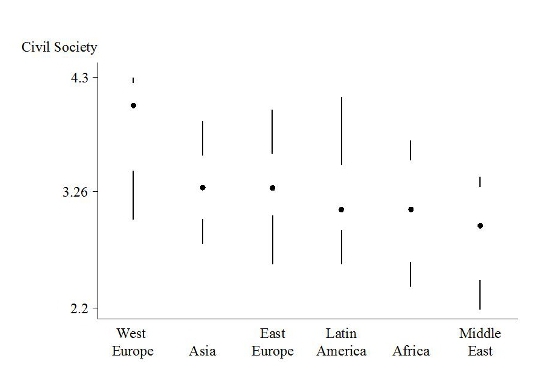

Figure 1 below shows the variation of civil society globally and within Europe itself. Whereas West European countries have on average strong civil societies, some East European countries – including post-soviet nations – maintain weaker civil societies than Asian or African countries.

Figure 1: Box Plots of Civil Society Index Scores by Region

Note: In this ‘box and dot’ plot, the median score for each world region is shown by the dot, with the range of country scores above and below the median level shown by the lines above and below the dot.

Looking at the CSI’s components it is apparent that some EU member states are at the lower end of the ranking. For instance, in terms of the structure of civil society, Greece, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, and Italy score lower than EU neighbourhood countries such as Armenia and Ukraine. In terms of the impact of civil society, Greece, Bulgaria, and Slovenia rank lower than Macedonia.

The key question is what drives the emergence of a strong civil society. There is no lack of in-depth country case studies, but few studies have been done on a broad comparative basis. In a recent co-authored paper with Stefanie Bailer and V. Finn Heinrich, I have attempted to do this using the CSI. Broadly speaking, previous studies have identified as driving forces for civil society the role of socio-economic development, societal structures, political institutions and international influences. The first two ‘bottom-up’ approaches comprise the size of the middle class, sociopolitical traditions, and ethnic and religious heterogeneity among other factors, whereas the latter two ‘top-down’ approaches refer to the level of political democracy and international development assistance. Can any of these factors claim to be a primary cause of civil society’s strength?

Based on 42 countries and using multivariate estimation techniques, we find that it is first and foremost the quality of a country’s political institutions that fosters the strength of civil society. Other factors such as the level of human development, the level and duration of democracy, societal trust or international influences are not correlated with civil society strength. Of course, the methodological problem is that multivariate regression techniques cannot properly establish valid causal relationships – the effect could still run from civil society to the quality of political institutions. But a controlled country comparison between Chile and Russia shows that it is the quality of political institutions that enables a strong civil society, not the other way around.

The results certainly need further scrutiny. But two implications are important for policy debates. First, the EU’s insistence on promoting civil society abroad rests on weak foundations, as some of its current and future member states have relatively weak civil societies themselves. Second, the hope that the promotion of civil society will prove an effective tool for improving political governance may be futile. This is not to argue for robust forms of conditionality, but rather to state simply that strengthening civil society is unlikely to be the magic bullet for improving governance – instead good governance is a prerequisite for a strong civil society.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/10VSHHZ

_________________________________

Thilo Bodenstein – Central European University

Thilo Bodenstein – Central European University

Thilo Bodenstein is Associate Professor in the Department of Public Policy at the Central European University, Budapest. His research interests include public policy, international political economy, development and transition studies and research methods.

I’m impressed by your analysis. I work as program quality and learning manager for CARE International in Uganda and part of my work is on research and documentation of best practices and lessons learnt. One of the key lessons we have learnt as a development agency that is in agreement with your paper is that many international development agencies and non-state actors have in the recent past focused a lot of attention and resources in working backwards. Supporting and strengthening civil society organizations with hope of building strong political and governance structures and institutions. Even CARE has done this a lot until recently when we learnt that our effort was going to the dogs. We were awakened by the realization that the political institutions we tried to influence have turned their guns against us. The recent appointment of a military general as minister of internal affairs here in Uganda and the barrage of threats issues to civil society organizations revealed just how wasted our efforts have been. This is a true confirmation of the validity of your thesis.