Coalition negotiations are continuing in Germany, following federal elections in September. André Krouwel, Theresa Eckert and Yordan Kutiyski use each of the major parties’ manifesto pledges to illustrate the state of the German party system in 2013. They note that the party system has become more polarised, with an ‘empty centre’ between those on the left and right of the political spectrum. The distance between Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU and the SPD gives an indication of the difficulty involved in forming a governing coalition. By analysing German voters’ party preferences and issue positions, they also provide a preliminary explanation of why the FDP failed to enter parliament for the first time in the party´s history.

Coalition negotiations are continuing in Germany, following federal elections in September. André Krouwel, Theresa Eckert and Yordan Kutiyski use each of the major parties’ manifesto pledges to illustrate the state of the German party system in 2013. They note that the party system has become more polarised, with an ‘empty centre’ between those on the left and right of the political spectrum. The distance between Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU and the SPD gives an indication of the difficulty involved in forming a governing coalition. By analysing German voters’ party preferences and issue positions, they also provide a preliminary explanation of why the FDP failed to enter parliament for the first time in the party´s history.

Germany’s Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) achieved an impressive result in the September federal election, gaining 41.5 per cent of the vote and thus recording the best result since the unification election in 1990, when CDU leader Helmut Kohl was at the height of his popularity. The social democratic SPD, on the other hand, recovered only slightly since their worst-ever election result in 2009 and received just over a quarter of the popular vote. This makes the CDU/CSU the dominant force in the Bundestag with 311 seats compared to the 193 representatives of the SPD. The Christian Democrats came up 5 seats short of an outright single party majority, yet their traditional coalition partner the FDP failed to reach the five per cent electoral threshold.

Clearly, government formation will be problematic. The Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats seem condemned to one another. To form a coalition, Angela Merkel has to reach out to the SPD, with negotiations likely to be protracted given the enormous policy differences between the two parties. The German political landscape is profoundly polarised after several years of economic crisis and austerity policies. Both the CDU/CSU and the SPD will have to abandon pledges that they made during the campaign to find some middle ground.

Of course, Merkel can claim that the austerity policies she has been implementing have received the blessing of the German voters, given the enormous increase in the CDU’s vote-share in the elections. Nevertheless, her coalition partner the FDP did not pass the 5 per cent electoral threshold for the first time in the post-war period. Now Merkel needs to deal with the SPD – after coalition talks with the Greens were amicably dismissed – to form a majority. Needless to say, the bargaining power of the SPD is considerable. Moreover, due to the failure of other right-wing or conservative parties to enter parliament, there is a small left-wing majority in the Bundestag. The likely grand coalition (SPD and CDU/CSU) would combine a vast 504 out of the 631 seats in German parliament, leaving only a strikingly small, and thus weaker opposition of Die Linke and the Greens.

German political landscape

For this election we developed a Voting Advice Application (VAA) “Bundeswahlkompass”, in which we positioned all relevant parties on 30 of the most salient issues, based on the official party stances in their manifestos. This party calibration can help us to understand where the parties agree and where they differ in their party programmes. It also allows us, by way of aggregating these party stances over the main political dimensions, to show the polarisation of the German party system in 2013. These centrifugal tendencies and the FDP´s vanishing from parliament will make coalition formation an arduous task.

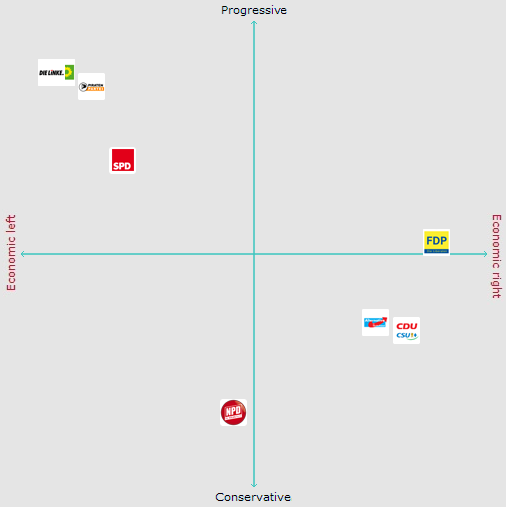

The German political parties were positioned along two main political dimensions: an economic left-right dimension and the cultural ‘progressive-conservative’ dimension. As Figure 1 illustrates, the striking clustering of the parties of the left and the substantial distance of all parties from the centre is immediately visible.

Figure 1: German political landscape

![]() Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU)

Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) ![]() Social Democrats (SPD)

Social Democrats (SPD) ![]() Die Linke

Die Linke

![]() Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen)

Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen) ![]() Free Democrats (FDP)

Free Democrats (FDP) ![]() AfD

AfD

![]() Pirate Party of Germany (Piraten)

Pirate Party of Germany (Piraten) ![]() National Democratic Party (NPD)

National Democratic Party (NPD)

Source: Bundeswahlkompass

The empty German centre

The CDU/CSU are uncharacteristically distant from the centre and positioned to the right on the socio-economic dimension. The SPD are located far from the centre as well and are situated close to the two other main left-wing parties: The Greens and Die Linke. The centre space is completely empty: a political ‘no man’s land’. The partisan polarity shows that the famous centrist tendencies of the German ‘Volksparteien’ – that Otto Kirchheimer referred to as ‘catch-all parties’ or “Allerweltsparteien’ – no longer exists in 2013.

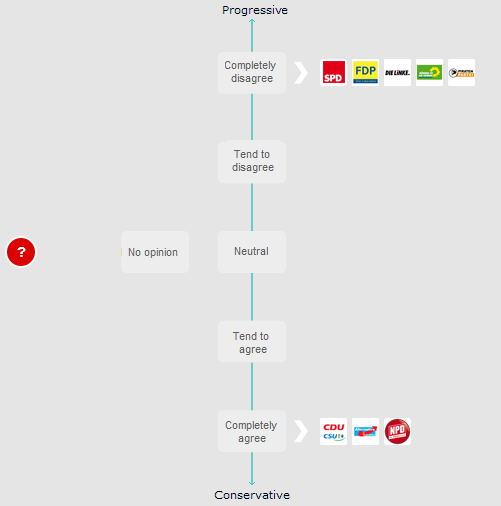

A strong political polarisation is visible on both the economic and cultural dimension. For example, on the economic dimension there is a clear divide between the left and the right. Figure 2 illustrates one example of this, with reference to the issue of introducing a national minimum wage. While the parties on the left are in favour of the policy, the parties on the right are vehemently opposed to it.

Figure 2: Positions of German parties on the statement: “A national minimum wage should be introduced”

Source: Bundeswahlkompass

Next to political polarisation on the economic dimension, German parties are also deeply divided over cultural issues. For example, on the topic of dual citizenship (see Figure 3) we can see a clear rift between the conservative parties (CDU/CSU, AfD and NPD) and the progressive-libertarian parties (FDP, SPD, Die Linke, Pirate Party, and the Greens). Both these issues are part of 10 demands that the SPD has recently voiced as crucial for a coalition formation. This signifies the deep differences between the possible coalition partners of the SPD and CDU/CSU, and shows the difficulties both parties will face when they jointly enter into government.

Figure 3: Positions of German parties on the statement: “Dual citizenship should not be accepted”

Source: Bundeswahlkompass

The strange disappearance of the FDP

This polarisation in Germany seems to have had the most serious impact on the Free Democratic Party (FDP). In the past, the Liberals were able to govern with either the Christian Democrats or the Social Democrats. Now the party seems to have been politically derailed by the centrifugal pull of the current political constellations, and has failed to pass the 5 per cent threshold. The FDP thus lost nearly 10 per cent of its vote share compared to the federal election in 2009 and is no longer represented in parliament. This is particularly striking since the Liberals had been represented in parliament since the founding of the Bundesrepublik in 1949 and were part and parcel of the political establishment. In fact, the 2009 election gave them the largest seat share in their history. Four years on, this has all evaporated.

The FDP also has a longer record of government participation than any other German party. For a total of 46 years the FDP was in government, mostly in coalition with the Christian Democrats, but also with the Social Democrats, and can thus be considered to have played a pivotal role in German government formation. The complete disappearance of the Liberals from parliament in 2013 is clearly a unique historic development, both for the party itself as well as for the German political landscape.

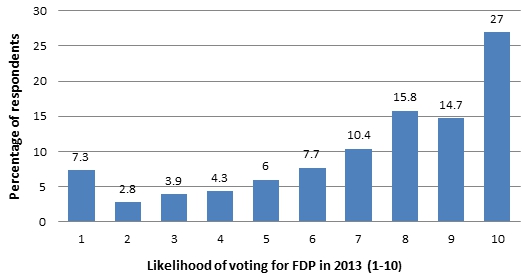

During the election campaign the “Bundeswahlkompass” was promoted through social network media and the German newspaper Tagesspiegel, with more than a quarter of a million Germans filling out the 30 issue questions. We also asked visitors to answer a small number of relevant background questions, which around 20,000 users did. Of these, more than 1,700 German voters indicated that they voted for the FDP in the 2009 Bundestag election. When we look at these former FDP voters, we see that more than 40 per cent indicate that they now support a different party (see Figure 4).

We asked all respondents to indicate how likely it was that they would ever vote for each of the relevant parties ranging from 1 (highly unlikely) to 10 (highly likely). Only 27 per cent of those who voted for the Liberals in 2009 were now still determined to do so (given that they gave the FDP a maximum score of 10). While we may assume that those who gave a score of 9 or 8 were also seriously considering the Liberals, it is clear that support for the FDP has decreased substantially among their previous supporters.

Figure 4: Likelihood of those who voted for the FDP in 2009 voting for the FDP again in 2013

Note: The figure shows the responses of 2009 FDP voters to the question “How likely would you be to vote for the FDP in 2013?” on a scale from 1-10 (1 being the least likely, 10 being the most likely).

Source: Bundeswahlkompass

The figures also indicate that a quarter of FDP supporters in 2009 now say it is very unlikely that they will vote for the FDP. With only just over a quarter of the liberal voters remaining loyal, we need to examine where these liberal defectors are moving.

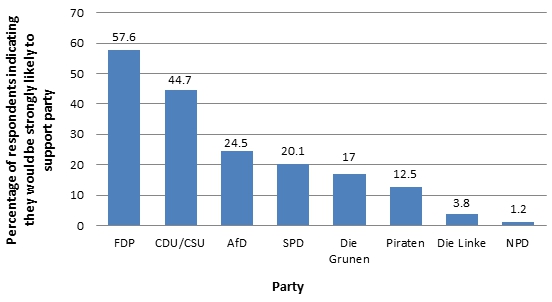

As Figure 5 illustrates, the CDU/CSU and the AfD were particularly likely (scores of 8, 9 or 10) to receive support from former FDP voters. In fact, almost 45 per cent of former FDP voters were seriously considering voting for CDU/CSU. This comes as no surprise as many centre-right voters in Germany traditionally have high vote propensities for both the Liberals and the Christian Democrats, and often split their vote between them. Nevertheless, it is fairly noteworthy when half of a party’s previous voters would strongly consider voting for an opponent.

Figure 5: Parties which FDP supporters in 2009 would be strongly likely to support in 2013

Note: The figures show the percentage of 2009 FDP voters who gave responses of “8, 9 or 10” to the question “How likely would you be to vote for this party in the 2013 elections?”

Source: Bundeswahlkompass

Even more startling is the enormous appeal that the new Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party had on liberal voters. A quarter of former FDP supporters indicated that they would seriously consider voting for the AfD, a party that is far more Eurosceptic and in favour of restricting immigration than the FDP. While 58 per cent of liberal supporters from 2009 were still considering the FDP, it also emerges that three out of four liberal supporters were seriously contemplating another option. This indicates the difficulty the FDP had in convincing their core supporters to remain loyal.

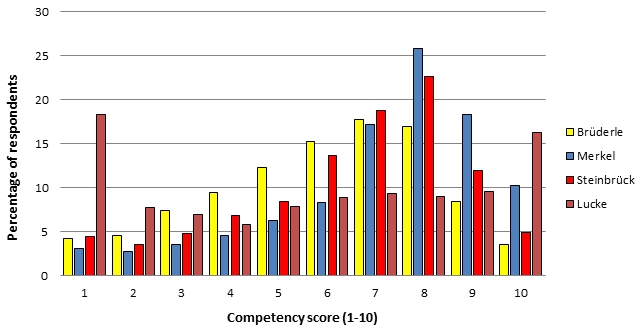

We can also assess whether there was any effect of the personal appeal of party leaders, as we also asked all respondents to tell us how competent they thought the various party leaders were. Figure 6 shows that many former FDP voters think Angela Merkel is much more competent than the FDP’s leader, Rainer Brüderle. This may not be as surprising as our finding that many also think SPD leader Peer Steinbrück is more competent than the Liberal party leader. In fact, many former liberal voters even consider newcomer Bernd Lucke, leader of the Eurosceptic AfD, more competent than Brüderle. These figures do not lie: the FDP had an important leadership problem. Many of their core voters seemed to consider the leaders of three other parties more competent than Brüderle.

Figure 6: Responses from 2009 FDP voters to the question: “How competent do you think the following politicians are?”

Note: Responses are on a scale from 1-10 (1 being least competent, 10 being the most competent).

Source: Bundeswahlkompass

Which voters abandoned the FDP?

When some standard background variables are considered, it is apparent that the FDP lost support from older voters and female voters in particular. This should be worrying for the Liberals, as this means that their traditional core vote could be disappearing. Those voters who remained loyal to the FDP tended to be the higher educated and those in higher income brackets. It is even more worrying for the Liberals that voters with a more right-wing orientation were contemplating a different party. In that sense, the FDP lost support from those who are in favour of more restrictive immigration policies. The anti-immigration factor seems to have had a significant role in reducing the party’s overall support. It seems that the liberals were haemorrhaging support on all sides.

Defection from the FDP also results from a more general dissatisfaction with the way that German democracy currently functions. Former FDP voters that were generally dissatisfied with German democracy and favoured a ‘strong-hand’ leader were also less likely to remain loyal to the Liberals. As shown above, the unpopularity of the FDP leadership also drove voters away from the party into the hands of – in their eyes – more competent politicians like Angela Merkel.

Since we asked voters for their opinion on a large number of relevant issues, we can also see which issues encouraged voters to abandon the FDP. On the economic dimension, former FDP supporters who object to the use of public money to rescue private banks largely switched their support to other parties, such as the AfD. Moreover, those who supported increasing financial support for the unemployed, increasing the top rate of tax, and introducing a minimum wage were also less likely to vote for the FDP. This suggests that the party not only lost support from those with firm right-wing views, but also among centrist voters, who shifted their support to other parties, in particular the SPD.

On the cultural dimension, the more Eurosceptic segment of former FDP voters now had a much more vocal anti-European option to support in the shape of the AfD, which advocated an end to financial support for southern European countries, and the reintroduction of the Deutsche Mark. Some more libertarian voters also switched support from the FDP to the SPD, particularly those in favour of closing nuclear power plants and ending the involvement of the German armed forces in military operations overseas. Former FDP voters with more conservative views, such as those opposing the legalisation of cannabis and adoption rights for same-sex couples, also shifted their support to the CDU/CSU. Given that the party was abandoned by libertarian, conservative, and Eurosceptic voters, it will not be easy to draft a platform in future elections that will automatically appeal to these three different voter groups and regain the support they attracted in 2009.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1cX3WH2

_________________________________

André Krouwel – Free University (VU) in Amsterdam

André Krouwel – Free University (VU) in Amsterdam

André Krouwel is associate professor at the Department of Political Science and the Department of Communication Science at the Free University (VU) in Amsterdam and is Academic Director of Kieskompas (Election Compass). His latest book is Party Transformations in European Democracies (SUNY Press, 2012).

Theresa Eckert – Freie Universität Berlin

Theresa Eckert is a Political Science bachelor student at Freie Universität Berlin and was part of the academic team that developed the Bundeswahlkompass.

Yordan Kutiyski – Free University (VU) in Amsterdam

Yordan Kutiyski is a MSc graduate in Political Science from the Free University (VU) in Amsterdam and a researcher at Kieskompas/VU University.