The issue of migration into Europe has once again generated headlines, following a number of incidents in which migrants have drowned at sea off the coasts of Italy and Malta in attempts to reach the EU. Considering the state of current EU asylum policy, Georgia Mavrodi reviews the data on EU asylum migration. She argues that the system does not adequately protect those in need and that fundamental reform is required to achieve a fairer and more equitable common EU asylum policy.

The issue of migration into Europe has once again generated headlines, following a number of incidents in which migrants have drowned at sea off the coasts of Italy and Malta in attempts to reach the EU. Considering the state of current EU asylum policy, Georgia Mavrodi reviews the data on EU asylum migration. She argues that the system does not adequately protect those in need and that fundamental reform is required to achieve a fairer and more equitable common EU asylum policy.

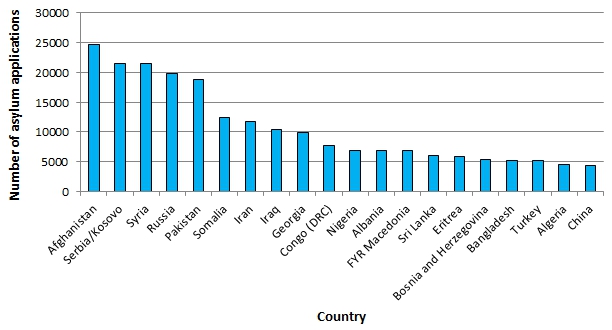

The recent tragic events off Lampedusa, Malta and Sicily, and the rising number of human lives lost in Mediterranean waters, have once again sparked debate on immigration and asylum policies in the EU. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 296,669 asylum applications were lodged in the EU’s 27 member states in 2012. Asylum seekers and refugees came to the EU from countries and regions of Africa, Asia and the Middle East, torn by armed conflicts, political and social unrest, and poverty. However, countries of eastern and south-eastern Europe also had their share. Chart 1 below illustrates these figures for the 20 countries with the largest numbers of asylum applications.

Chart 1: Origin of asylum applications lodged in the EU in 2012 (top 20)

Source: UNHCR

Constructing a common EU asylum system with fair and effective procedures for the protection of those in need of international protection has been a declared goal of EU integration since the late 1990s. Two main frameworks currently exist to regulate asylum issues in the EU. The first is the adoption of a common set of principles and regulations for controlling external borders and defining the member state responsible for examining each asylum claim filed in the EU. The second is the progressive harmonisation of the treatment of refugees and asylum seekers across EU member states.

The former has fallen under heavy criticism for raising a “Fortress” around the outskirts of Europe, a barbwire line that is difficult to cross for those in need of international protection, often resulting in human rights violations. By contrast, the step-by-step process of harmonising the treatment of asylum seekers and refugees has led to the consolidation (in some cases, such as the “new” immigration countries in the EU, even to liberalisation) of the legal provisions on the reception of asylum seekers, their recognition as refugees and the rights bestowed upon them across the EU.

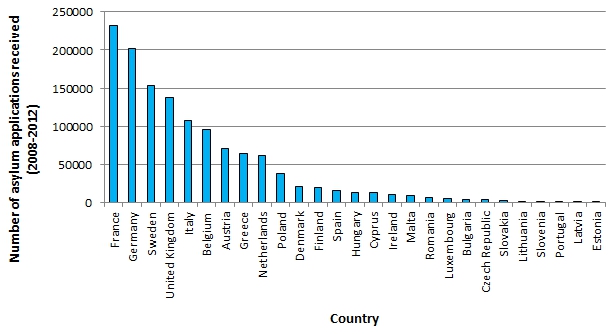

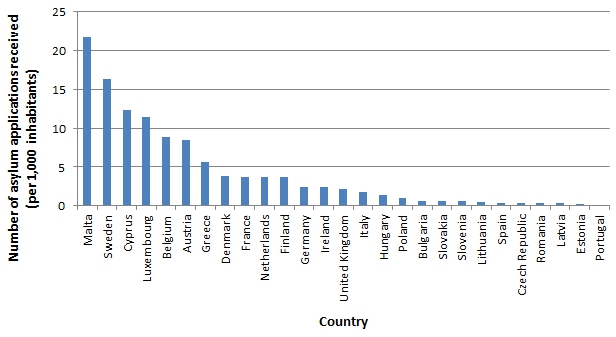

The overall picture is far from uniform, as the size and composition of the population of asylum seekers in each EU member state differ substantially. In 2011, asylum applications by Afghan nationals were submitted mainly in Germany, Sweden, Austria and Belgium, while Pakistani nationals applied for asylum mostly in the UK, Germany, Greece and Italy. Germany, Belgium, Sweden and the Netherlands attracted a large number of asylum applications lodged by Iraqis, and Russians preferred asking for asylum in France, Poland, Austria and Belgium. Between 2008 and 2012, France, Germany, Sweden, the UK and Italy were the top-five EU countries for receiving asylum applications in the EU. Yet it was Malta, Sweden, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Belgium, Austria and Greece that received the highest number of asylum-seekers compared to their population. Chart 2 indicates the EU countries receiving the highest number of asylum applications between 2008 and 2012, while Chart 3 shows the EU countries receiving the highest number of asylum applications relative to population.

Chart 2: Number of asylum applications received by EU countries from 2008-2012 (absolute)

Source: UNHCR

Chart 3: Number of asylum applications received by EU countries from 2008-2012 (per 1,000 inhabitants)

Source: UNHCR

Source: UNHCR

The implementation of commonly agreed EU principles and regulations, which differs across member states, is also a key factor. Greece often gets international headlines for its bad reception conditions, long delays in examining asylum claims and low refugee recognition rates compared with the rest of the EU. Italy, too, is often criticised for low standards in receiving asylum seekers and for turning a blind eye to them continuing their journeys from Italy to other European countries.

At the same time, these countries, along with Malta and Spain, have repeatedly stressed the need for burden-sharing and active EU solidarity when it comes to the reception of refugees, the examination of asylum applications, and the patrolling of their external borders. Financial assistance (such as the European Refugee Fund and the European Integration Fund) and operational support and transfer of knowledge (including the European Asylum Support Office and FRONTEX, the EU borders agency) have been institutionalised, but they are not deemed to be enough. Finally, national courts in some member states (Germany, the UK and Belgium, among others) have successfully challenged the common EU principle of returning asylum seekers to the country of their first entry into the EU if common European reception standards and/or the guarantees for their recognition as refugees are not fully respected.

All the above considerations and debates notwithstanding, the recent tragic losses of life and the rescue of many more off Lampedusa, Malta, and Sicily underline the need to rethink the nature of the EU asylum system and the burdens it places upon the very people it is expected to protect. The fact that refugees and asylum seekers are offered protection once they set foot on EU territory means in effect that people from third countries often need to embark on long, costly and dangerous journeys in which they are exploited by highly-profitable international smuggling and/or trafficking networks. They risk persecution, their health, and even their lives in order to enter the EU. For tens of thousands who attempt to cross the Mediterranean from Tunisia or Libya to Italy and Malta every year – as well as for the thousands who are trying to reach the Greek islands from Turkey – lodging an asylum application in Europe comes only after a personal and/or family investment of thousands of dollars has been made, often over the course of years, leaving them in a state of irregularity, precariousness and exploitation in countries of transit.

It becomes obvious that these realities result in a harsh selection of those who finally make it: contrary to prevailing assumptions, these are not necessarily the most vulnerable, the most in need or the most desperate for protection. Rather, they are the ones who manage to mobilise more resources, more strength, and more persistence – and those that are lucky not to lose their lives as a result. These realities also keep the vast majority of refugees outside the EU, letting the EU’s poorer neighbours bear a burden much greater than the EU itself, as the case of the hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey demonstrates. Evidently, such a system is neither fair nor effective in offering international protection. It equally does not contribute to sharing the burden of that protection among states and people alike.

A truly common, fair and effective asylum policy would need to include new EU institutions. This would mean a new EU agency to register asylum applications both within and outside the EU, in close cooperation with the UNHCR. It would also mean a common set of criteria across the EU for examining asylum applications submitted outside the EU and for re-distributing asylum seekers among the member states once they have crossed the EU’s external borders.

At the same time, it would incorporate institutions to oversee and support the implementation of the common principles and standards for the reception of asylum seekers, the examination of asylum applications and the determination of refugee status and other forms of international protection, accompanied by a new system of fair distribution of resources for refugee resettlement from third countries and among member states. Recently adopted programmes for voluntary refugee resettlement and strengthening the capacity of some member states in examining asylum applications, such as the EUREMA project for Malta and the assistance offered to Greece by the European Asylum Support Office, may be the first steps in such a process, and give incentives for rethinking EU asylum policy, refugee protection and burden-sharing on a new basis.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/IdnQDm

_________________________________

Georgia Mavrodi – European University Institute

Georgia Mavrodi – European University Institute

Georgia Mavrodi is Researcher in the Robert Schuman Center for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. A graduate of the University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, the University of Bath, Humboldt University of Berlin and the EUI, she has taught at European and American Universities and held the Hannah Seeger Davis Post-Doctoral Research Fellowship in Hellenic Studies at Princeton University in 2011-2012. She has published extensively on immigration and migration policy in the EU.

Asylum should be dealt with at the point of arrival, the UK already has millions of Economic Asylum cases from eastern Europe to assimilate into society The best place to locate new arrivals is in Eastern Europe to replace the millions that have fled to UK, France, Germany.

While I can accept that processing asylum applications has never been a fair process, I do think it’s a bit unfair to suggest Eastern Europe should pick up the tab. Most of the people who have moved from Eastern Europe to the UK, France, Germany and so on are productive workers, so we’re basically talking about a country like Poland losing a large chunk of productive individuals and replacing them with asylum seekers (who of course are there on humanitarian grounds, not to work). They’re also much smaller economies, which makes the impact greater – the UK receives among the smallest numbers of asylum applications in relation to GDP per capita of any country in Europe.

Asylum is a humanitarian issue. The argument is that we all, as human beings, have some obligation to help people in need – refugees, victims of war, and so on. It should be based on capacity to help, not where a country is located on a map. As the third Chart here shows, the UK isn’t anywhere near the top when it comes to asylum applications by population. At present we’re contributing a paltry effort in comparison to many other EU countries, yet kicking our heels and moaning about it at the same time. The idea that the UK is a soft touch with asylum seekers is just patent nonsense when you look at these statistics and those in the UN report linked above.

We are picking up the tab for Eastern Europe’s Economic Asylum Seekers & lets face it most of those seeking entry into the EU are economic asylum seekers but the EU is too terrified of the race card & the PC brigade to simply send these illegal immigrants back to where they came from. We know amongst these types of illegals are hidden sleeper cells for terrorist organisations so it is far better to deal with their issues on their soil rather than bring their warped minds to Europe. Because Eastern Europe is a part of the EU & we cant stop them migrating to our shores does not make them any less of an Asylum case than say someone from Iran or Burma. We have taken in over a million East Europeans so lets not say the UK isn’t near the top of the table in doing its bit.

Why don’t you go back to the Daily Mail, Joe Thorpe, where bitching about ‘the PC brigade’ is acceptable and facts & reasonable arguments can be conveniently ignored?

How many homeless have you taken in and helped back on their feet?Also,PC is a very real issue,and supporters for allsorts of do-goodery paid for by somone else is also rife.

Mr Sutton,your this remark is puerile.Talk about the Daily Mail.I would not care to know what you read to keep up with events,but it cannot be better than the daily fail.