Earlier this month, the European Central Bank cut its benchmark interest rate to a new low of 0.25 per cent, down from 0.5 per cent. Frances Coppola writes that the rate cut is unlikely to offer any help to the struggling economies in southern Europe. She argues that the rate cut was framed largely around the interests of Germany, and that the actions the ECB really needs to undertake are politically impossible.

Earlier this month, the European Central Bank cut its benchmark interest rate to a new low of 0.25 per cent, down from 0.5 per cent. Frances Coppola writes that the rate cut is unlikely to offer any help to the struggling economies in southern Europe. She argues that the rate cut was framed largely around the interests of Germany, and that the actions the ECB really needs to undertake are politically impossible.

Consumer price inflation in the Eurozone has been below the target of 2 per cent and falling for quite some time. But until now, the ECB has been sitting on its hands. Inflation some distance below target didn’t appear to bother it – most likely because the (unbelievable) forecasts for Eurozone recovery created inflation expectations in the 1.5 – 2 per cent range, so it saw no need to act on what was assumed to be a temporary problem.

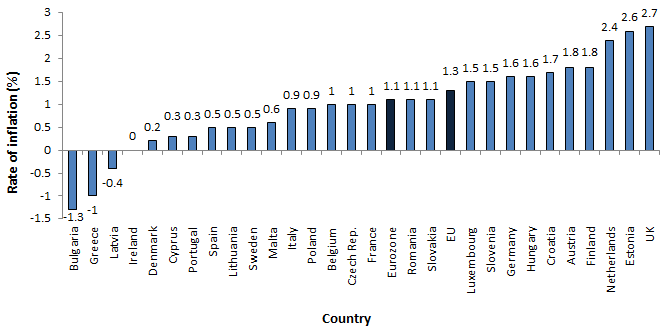

So why did the ECB, in a complete reversal of its previous stance, suddenly cut the interest rate to 0.25 per cent? Well, Eurozone consumer price inflation has touched a record low of 0.7 per cent, driven by falling energy prices and stagnant prices in other sectors. But inflation expectations are still where they were before, based on expectation of a strong Eurozone recovery. Below is a Eurostat Chart showing inflation rates by country as of September 2013.

Chart 1: Inflation rate in European countries in September 2013 (%)

Note: Data for Austria are provisional.

Source: Eurostat

And Reuters reports that German inflation has unexpectedly fallen to 1.2 per cent in October. Well, well. German inflation is below target and falling. So the ECB is doing what the ECB does: responding to German monetary indicators. I suppose this is inevitable, since Germany is the dominant economy in the Eurozone. But it just shows how impossible a one-size-fits-all monetary policy really is where there are such disparities of size and competitiveness between countries in a monetary union. Monetary policy is inevitably driven by the needs of the largest, even if it is actually damaging to the smallest.

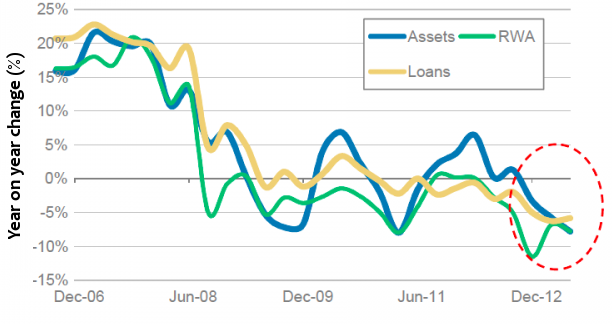

And damaging it certainly is. The monetary policy transmission mechanism in Europe depends very much on banks. And European banks are a dysfunctional lot. They are loaded up with poor quality sovereign debt, which bizarrely they can still hold without additional capital allocation, even though it is anything but risk-free. And they are deleveraging at a rate of knots as Chart 2, from Morgan Stanley (via Business Insider) demonstrates.

Chart 2: Annual change in value of assets of EU banks (2006 – 2013)

Note: Data based on around 250 banks in western Europe holding 35 trillion euros of assets. Figures run through the second quarter of 2013. In 2013 these assets fell by 2.7 trillion euros (year on year), while from the first to the second quarter of 2013, they fell by 1 trillion euros. RWA refers to Risk-Weighted Assets.

Source: Morgan Stanley Research, SNL Financial, company reports.

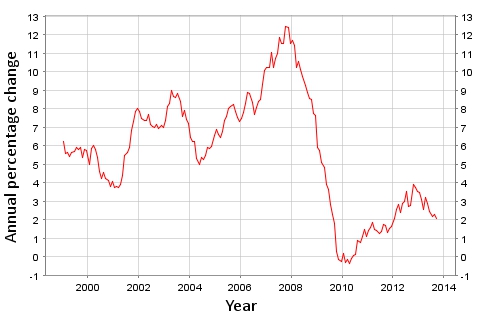

When banks deleverage, broad money falls. As Chart 3 shows, Eurozone M3 (the broadest measure of money supply in the Eurozone) has been falling for most of 2013.

Chart 3: Annual percentage change Eurozone M3

Source: ECB’s Statistical Data Warehouse

Eurozone banks don’t want to increase risky lending. They are busy reducing balance sheet risks. So they don’t want to lend to businesses in riskier parts of the Eurozone. Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) lending rates in Spain and Italy are far higher (£) than they are in Germany, which makes those businesses uncompetitive. This refi rate cut is not going to mean lower rates for them: it will mean lower rates for German businesses, already benefiting from the Eurozone’s bifurcated credit market. So the Eurozone countries that really need lower interest rates aren’t going to get them because of dysfunctional banks and worries about sovereign solvency. Instead, their competitiveness is going to be hammered again.

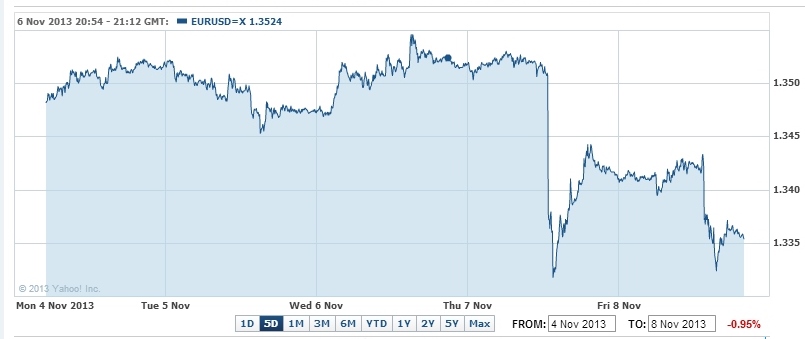

The problem is that cutting the refi rate pushed down the value of the euro. As Chart 4 shows, it fell like a stone when the rate cut was announced, and although it rose a bit it didn’t return to its previous value.

Chart 4: Value of the euro relative to the US dollar (4 – 8 November)

Source: Yahoo

This will provide a boost to German exporters – who are the last people in the world to need such encouragement. Coming on top of Germany’s generally mercantilist stance (“hands off our trade surplus“), it is difficult to see how a falling euro would improve domestic demand. It seems more likely that it would increase exports.

No doubt some people will argue that a falling euro would benefit periphery exporters. But I’m afraid they are mistaken. I’ve already pointed out that this rate cut will reduce borrowing costs for German businesses but not for periphery ones. The fall in the euro will mitigate high borrowing costs for periphery businesses to some extent, but it will also benefit German businesses in addition to the benefit they will get from lower borrowing costs. Overall, therefore, German businesses will benefit more than periphery ones. This rate cut actually worsens the periphery’s competitiveness problem. Of course, it can be argued that German and, say, Spanish exporters don’t directly compete because they are in different markets. But if Spanish exporters are competing with, say, Chinese, the fall in the euro will make little difference (because the yuan is managed) and the ECB’s inability to influence lending rates to Spanish businesses means that Spanish exporters will not benefit at all: meanwhile Germany will do even better in its export markets.

In fact a falling euro is helpful to nobody. The Eurozone as a whole has a trade surplus. Yes, periphery countries still have trade deficits, although these are reducing – but the trade surplus in the core is so enormous now that the periphery deficits no longer offset it. The Eurozone as a whole does not need currency depreciation. So the ECB’s actions in support of Germany actually make matters worse for the periphery. And it is still sitting on its hands in regard to the real problem in the Eurozone, which is the deepening depression in Southern Europe and Ireland. In fact I fear that it is not sitting on its hands, it has washed them – because it seems to me that the ECB is actually incapable of dealing with the depression in Southern Europe.

Scott Sumner argues that the ECB is not yet out of firepower and that fiscal policy is impotent because rates are still above zero. But I fear Sumner is making a fundamental mistake. The Eurozone is not a homogenous area. Real rates in the periphery are far higher than they are in Germany, and the bifurcated credit market makes it impossible for the ECB to force down rates. The ECB simply is not in control of monetary conditions in the periphery. Conversely, real rates in Germany are probably negative: I doubt if this rate cut is anywhere near enough to raise inflation in Germany. The divergence between the periphery and the core widens all the time. There are still things the ECB could do, but a short run-down of some of them shows how limited they are.

First, the ECB could do another round of long-term loans (LTROs). The problem with this is that it is a racing certainty that the new LTRO money would be used yet again to buy up sovereign debt, which would reinforce the disastrous dependency of sovereigns on banks and vice versa.

Second, it could cut the deposit rate to negative, thus charging banks for safe assets. The problem with this is, of course, the existence of physical cash. To have much impact, the deposit rate would have to be quite significantly negative, in which case there is a serious risk that banks will simply hoard vaulted cash instead. Alternatively, they could buy up sovereign debt instead of hoarding cash, which creates the same problem as LTROs. And it is worth remembering that German bunds are substitutes for euro reserves: the short-term yield on bunds would therefore also drop into negative territory. Should we really be paying to lend to the German government?

Third, it could stop accepting weekly deposits. Various people seem quite keen on this idea. The deposits in question are used to sterilise the money issuance consequent on the ECB’s buying of some sovereign debt as part of its normal open market operations. But I don’t see how it could possibly work. The ECB can’t stop banks leaving money in their reserve accounts. The amount of reserves in the system is what it is, and someone has to hold them. The idea that reducing reserve requirements or eliminating the requirement for open market operations to be sterilised will give banks more funds to lend shows a lack of understanding of how the banking system works, which is worrying given that one of the people suggesting this is a member of the ECB’s governing council. Banks don’t “lend out” deposits. And they don’t “lend out” reserves.

Finally, it could do some form of quantitative easing (QE). Exactly what assets it would purchase is not clear. It could be based on the ECB’s list of eligible collateral, but this is very extensive and much of it decidedly dodgy: the Eurosystem governors may not be too happy about the ECB actually owning this stuff (as opposed to simply accepting it as collateral). So presumably the assets the ECB would purchase would only be “safe assets” – i.e. government debt. This immediately causes a problem. OMT – the pledge that the ECB made to buy up periphery government debt under exceptional circumstances – has strict conditionality attached to it. Is the same conditionality going to apply if these assets are purchased as part of a general QE programme? If so, then the ECB would be making fulfilment of its mandate to ensure price stability conditional on fiscal rectitude by periphery government – so much for ECB “independence”. And if not, then what credibility would OMT have any more? So QE is either impossible or useless while the OMT conditionality exists.

What the ECB really needs to do is improve monetary policy transmission to the periphery. This could involve the following: direct purchases of corporate and sovereign bonds; some form of GSE structure to pool and securitise SME loans so that they could be purchased as well; or in Spain, Ireland and Portugal, direct purchases of residential and commercial mortgages.

And it also needs to reflate the periphery economies. This would mean either “helicopter drops” or purchases of sovereign debt. The two could be combined, which would amount to a form of QE targeted at distressed sovereigns. But that means removing the conditionality of OMT, which exists to avoid the charge that the ECB is monetising the debt of fiscally irresponsible sovereigns. Monetisation of sovereign debt is explicitly outlawed by the EU’s treaty framework. Even though OMT is so hedged around with conditionality that it has never been used, it has already been subject to legal challenge. I have no doubt that if the conditionality were removed to allow the ECB to reflate the periphery economies there would be howls of protest and a spate of lawsuits from Germany, which has an almost religious belief that monetisation will inevitably lead to hyperinflation, despite the complete lack of evidence that reflation in a depression has any such effect.

Reflation of Germany cannot be done by monetary policy alone, either. For Germany to recover, the whole Eurozone must be healed. While Germany continues to insist that the problems of Southern Europe are not its concern, it too will remain in the doldrums. Though there are plenty of people in Germany who are very happy with zero inflation: there has been extensive criticism of the ECB’s action from German media concerned about rising property prices and poor returns for savers. The ECB may be doing its job, but the principal beneficiary doesn’t seem to want it to do so.

As far as I can see, all the actions that the ECB really needs to take are politically impossible. I have been severely critical of the ECB’s handling of the Eurozone crisis: it has gone way beyond its mandate in imposing fiscal conditionality on sovereign states, and it has failed to address the deepening depression in a growing number of Eurozone states. But I acknowledge that the real problem is the political set-up in the Eurozone. It is not just OMT that is so hedged around with conditionality that it is virtually useless. It is the ECB itself.

This article first appeared on Frances Coppola’s personal blog, Coppola Comment

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1bMGMnE

_________________________________

About the author

Frances Coppola

Frances Coppola

Frances Coppola has an MBA from Cass Business School. She designed risk management systems for Treasury and Capital Markets at NatWest, and a group consolidated financial and regulatory reporting system for RBS Group. She is the author of the Coppola Comment blog, as well as the Singing is Easy blog, where she writes about singing, teaching and musical expression. She tweets @Frances_Coppola

Just a bit troubling to see “Eurozone M3 (the broadest measure of money supply in the Eurozone) has been falling for most of 2013” for its rate of *growth* declining from 4% pa to 2%. A slowing, yes, but would you really want to call it “falling” ?