According to a poll carried out earlier this year, more than a third of French voters agree with the ideas of the Front National. Nonna Mayer finds that these results highlight a seeming “droitisation” in France: the normalisation of the radical right as an established element of mainstream politics. By looking at the shift in values among traditional working-class voters, she attempts to explain changes in citizens’ perception of the radical right.

According to a poll carried out earlier this year, more than a third of French voters agree with the ideas of the Front National. Nonna Mayer finds that these results highlight a seeming “droitisation” in France: the normalisation of the radical right as an established element of mainstream politics. By looking at the shift in values among traditional working-class voters, she attempts to explain changes in citizens’ perception of the radical right.

The Front National has become a normal part of mainstream politics in France. This is the main lesson of a poll carried out earlier this year. This survey has highlighted a significant change in the perception of the party since the early 1980s, a phenomenon which has become known as “Droitisation”. “Droitisation” is a fashionable but tricky concept. Basically it means a shift to the right. But is that shift a small or a big one? Is it towards the right or the extreme right? A mere relocation or a shift in values? And is it affecting only a group or French society at large? Or many other countries as well? To make things clear, one must disentangle these different meanings.

In France, the term “Droitisation” was first coined to account for the electoral realignment of the working class, which used to be a stronghold of the Left. The decline of industry, the expansion of the service sector, the salaried middle class, and the transformation of social democratic parties into middle-class parties loosened the links between workers and the parties of the Left. The first round of the 1978 French parliamentary elections marked the climax of workers “class voting”, when 7 out of 10 voters supported socialist or communist candidates.

However, by the first round of the presidential election of 1981, the figure was down to 66 per cent, by 1995 below 50 per cent, and by 2007 it was just 38 per cent. If one compares workers to non workers, the picture is even clearer. In 1978 the score of the Left among workers was 17 percentage points above their national score. By 2002 there was no longer any difference. This trend has been going on for some forty years in France, but it has taken on a new significance since 2012 following work by the progressive think tank Terra Nova.

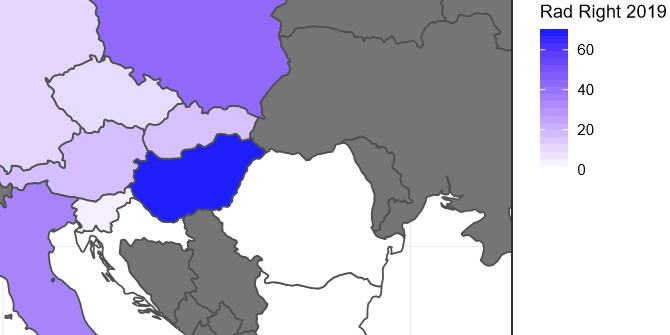

A second meaning of “droitisation” is “extremisation”. All over Europe, far right parties are gaining influence. In 2012, Marine Le Pen brought the Front National its best score in a presidential election, improving her father’s record in the 2002 election by one percentage point and 1.6 million votes. In doing so, she drew some thirty per cent of the working class votes. But here again the Front National has been electorally successful since the mid 1980’s, and in the first round of the 1995 presidential election, Jean Marie Le Pen already came first among skilled and unskilled manual workers.

In a third sense “droitisation” refers to a value shift towards the right. The annual Barometer survey on racism, anti-Semitism, and xenophobia for the National Commission for Human Rights (CNCDH) shows an inflection point in 2010. Intolerance toward immigrants, foreigners, and Muslims, which had been declining consistently since 1990 has been increasing for a third consecutive year. Yet a closer look at the data shows that on our global indicator of tolerance, the score of respondents who locate themselves on the left on the traditional left right scale has practically not changed in those same three years.

Only among the right and centre right respondents is intolerance on the rise. A radicalisation of the French right is taking place, moving its centre of gravity more to the right, towards positions, on immigration and Muslims, very close to those defended by Marine Le Pen. The massive protests against gay marriage, last spring, tell the same story.

Last, is “droitisation” a general move towards the right in Western countries hit by the “Great recession”? The very careful analysis done by Larry Bartels, comparing 42 elections in 28 OECD countries from 2007 to 2011 tells another story. Voters did not swing to the right, they simply punished incumbents, regardless of the voters’ ideology. Of the four meanings of “droitisation”, this last one is certainly the most worrying for François Hollande. Elected by many voters who just wanted to punish Sarkozy, he will have to make sure they don’t want to punish him, in 2017.

This article originally appeared at Policy Network

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1bPI4Ky

_________________________________

About the author

Nonna Mayer – Sciences Po

Nonna Mayer – Sciences Po

Nonna Mayer is Research Director at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) and a professor of Political Science at the Centre d’études européennes, Sciences Po.