The European Parliament elections in Romania will be held alongside a constitutional referendum, and ahead of Presidential elections in November. Clara Volintiru writes that while the elections will serve as a ‘dress rehearsal’ for the Presidential elections later in the year, they will potentially have wider significance for Romanian democracy. She argues that given the fragile governing coalition and continuous transformations of political parties within Romania, the results are likely to have a substantial impact on the country’s governing and electoral dynamics.

The European Parliament elections in Romania will be held alongside a constitutional referendum, and ahead of Presidential elections in November. Clara Volintiru writes that while the elections will serve as a ‘dress rehearsal’ for the Presidential elections later in the year, they will potentially have wider significance for Romanian democracy. She argues that given the fragile governing coalition and continuous transformations of political parties within Romania, the results are likely to have a substantial impact on the country’s governing and electoral dynamics.

Politicians in Romania have found themselves in an increasingly perplexing situation, in which some of them are even unable to tell the press what party they belong to. While this situation might be due to their personal lack of political commitment, it is equally a result of the ever-changing political climate during the past year. Alliances form, and then become obsolete in a matter of months. New parties rise with the same political leaders as before, and throughout all this rotation of roles the position of the electorate becomes harder and harder to monitor.

Far from being an event of marginal electoral significance, the 2014 elections for the European Parliament in Romania are likely to be one of the most important political events in recent years. The stakes in this electoral cycle go beyond representation in the European Parliament; they will serve as a test of electoral strength for the highly contentious presidential elections, scheduled in the second half of this year. As such, based on the electoral results in May, significant shifts in the political coalitions are likely to occur.

There are two sets of issues at the heart of these European Parliament elections: policy issues and national political issues. In a somewhat unfortunate manner, the national political issues are likely to take centre stage, diverting attention away from more poignant, stringent, and significant policy issues. Against this backdrop, opinion polls reveal that 67 per cent of the population are disillusioned with the political process in Romania.

In terms of policy expectations, according to a recent poll, the main issues concerning the Romanian population are financial problems, such as low incomes, high prices (28 per cent of respondents identify this as an important issue) and unemployment (17 per cent), corruption (14 per cent), the quality of health care (11 per cent), infrastructure (7 per cent) and issues regarding agricultural activity (4 per cent). Beyond these specific worries, there are wider concerns about the state of democracy and rule of law.

In the run up to political contests the lines between the political sphere and the judicial one have at times been blurred. As such, a general climate of distrust and instability has gradually spread across the country. This will culminate in the double voting for European Parliament elections and a national referendum on the new draft of the Romanian Constitution. Therefore, like the Czech Republic and Italy, Romania will have a two-day election period for the European Parliament. The new Constitution is likely to pass the referendum, but it remains to be seen to what degree it will improve the framework of Romanian democracy.

The electoral contest for the 32 Members of the European Parliament in Romania is expected to bring deeper political issues to the fore. Under a general climate of political instability, the elections will continue to act as shifting tectonic plates for Romanian democracy. A precarious equilibrium has been sustained since 2012, with a coalition government encompassing a wide political spectrum, the Social Liberal Union (USL). This coalition includes Prime Minister Victor Ponta’s centre-left Social Democratic Party (PSD), the main representative of the right, the National Liberal Party (PNL), the Conservative Party (PC), and the National Union for the Progress of Romania (UNPR). However in the coming European elections they will stand on separate lists, suggesting that it is unlikely the governing coalition will stay united until the presidential elections in autumn this year.

For the European Parliament elections, the PSD will run in an alliance – the Social Democratic Union (USD) – with the UNPR and the PC, which is actually a reunion of a previous composition of the Social Democratic Party. Another important aspect to be considered is the evolution of a newly formed political party, the Popular Movement Party (PMP), where most of the former government elites of the Democratic Liberal Party (PD-L) have regrouped. It is widely considered to serve as a strategic move by the incumbent president Traian Băsescu. Whether or not the PMP will manage to gain seats in the European Parliament, it is still likely to decrease the margins of the PD-L, effectively splitting the opposition.

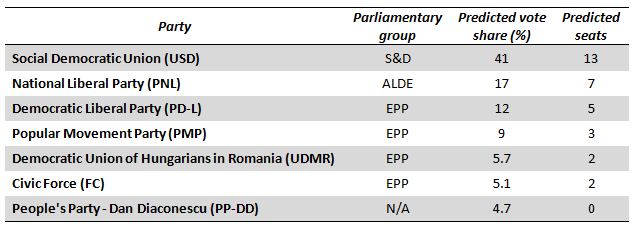

The latest polls suggest that the USD has the support of 42 per cent of the electorate. Of the other major parties, the PNL sits at 20 per cent, while the PD-L has 18 per cent. Although other parties currently don’t meet the Romanian electoral threshold of 5 per cent, a lot could change in the following months. The Table below shows party support, based on a recent CSOP poll.

Table: Party support in Romania (Updated 1 March 2014)

Source: Updated 1 March; seat predictions from Pollwatch2014.

These percentages suggest in the case of the Social Democrats an increase in the number of existing MEPs for the following Parliament. While it is unlikely that the European Parliament’s overall balance of power will change substantially, the parliamentary group of the Social Democrats (S&D) will benefit from this increased representation in Romania.

Beyond the final results, the divisive background of the elections presents two wider risks. Firstly, there is a serious governance deficit, with all political parties heavily preoccupied with their electoral and organisational survival. While the economic indicators tend to show a somewhat effective administration, if institutional processes carry on in this manner they might cause more grievances.

Secondly, the disenchantment and confusion of the population towards the political class will make the representation function of the coming elections largely invalid. Whoever will take office in the European Parliament, or in national positions, is unlikely to be held accountable by voters. As such, a larger discussion on the quality and process of democracy is necessary, in a time of frequent elections.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1h86hAA

_________________________________

Clara Volintiru – LSE Government

Clara Volintiru – LSE Government

Clara Volintiru has a PhD in Political Economy, and is currently a PhD candidate in Political Science at the Government Department, LSE. She holds an MSc in Comparative Politics, from the LSE, and an MBA from CNAM, Paris. Currently, she is associate analyst for PRIAD. Her research is focused on political parties in new democracies, informal politics and institutionalism—topics covered in various articles and books.

1 Comments