Hungarian Parliamentary elections are scheduled for 6 April. As Johannes Wachs and Lise Herman write, the Crimea crisis has inevitably formed part of the backdrop to the campaign, with over 100,000 Hungarians currently living in Ukraine. They note that the current government, led by Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party, has been slow to criticise Russia, in line with its ‘eastward shift’ in foreign policy. Yet there is a fundamental tension between Fidesz’s aim of pursuing closer relations with Russia and their anti-Communist rhetoric, which seeks to associate their parliamentary opposition with the former-Soviet past.

Hungarian Parliamentary elections are scheduled for 6 April. As Johannes Wachs and Lise Herman write, the Crimea crisis has inevitably formed part of the backdrop to the campaign, with over 100,000 Hungarians currently living in Ukraine. They note that the current government, led by Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party, has been slow to criticise Russia, in line with its ‘eastward shift’ in foreign policy. Yet there is a fundamental tension between Fidesz’s aim of pursuing closer relations with Russia and their anti-Communist rhetoric, which seeks to associate their parliamentary opposition with the former-Soviet past.

Polish Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski has taken a leading role in coordinating the European Union’s response to the Ukrainian crisis. Poland’s demographic and economic importance justifies its involvement, but its claim to a voice is also legitimised by the history of Central and Eastern Europe. While a firm position could have also been expected from other actors in the region, the Hungarian government was slow to condemn the repression of Maidan protesters and Russia’s activities in Crimea. This is consistent with Hungary’s current foreign policy, reoriented towards the East since 2010. With public opinion divided on Fidesz’s Eurosceptic stances, the government’s reluctance to criticise Russia gives ammunition to the opposition, only weeks ahead of the elections.

A muted response

Statements from Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán have focused on the security of the 156,000 person Hungarian minority rather than the issue of Russian-Ukrainian confrontation. After several days of silence, Prime Minister Orbán’s first comment on Russia’s intervention in Crimea on 3 March was that “Hungary is not part of the conflict”. While the Foreign Ministry was quick to support the EU’s stance in opposing Russia’s manoeuvres, political actors with greater domestic presence have followed Orbán’s lead. On the same day, the speaker of the National Assembly, László Kövér, focused on the new Ukrainian government’s repeal of the minority language law, in his first public remarks on the crisis since Russia’s involvement.

Most tellingly, Prime Minister Orbán’s statement on 4 March, ahead of the 6 March EU summit in Brussels, contained no reference to Russia at all. This can be compared to the joint statement released by the prime ministers of the Visegrad Group, including Prime Minister Orbán on the same day. The former calls for diplomacy with Russia to bring about a peaceful conclusion to the crisis and pivots attention to the rights and safety of the Hungarian minority. The latter declares Russian military action a violation of international law, and states that the countries are “appalled to witness a military intervention in 21st century Europe akin to their own experiences in 1956, 1968 and 1981”. This contrast suggests that the Prime Minister is unwilling to individually criticise the Russian position.

Reorienting Hungary’s diplomacy towards Russia

This stance can be understood within a wider reorientation of Hungary’s foreign policy since the 2010 elections. The controversial legislative changes initiated by Fidesz’s two-thirds majority, including a new media law, passed on 21 December 2010, and a new Constitution, amended five times since its adoption on 18 April 2011, have spurred confrontation with EU institutions. The European Commission launched three accelerated infringement procedures on 17 January 2012, targeting the independence of the judiciary and of the Central Bank. The European Parliament has also exercised pressure, adopting a first resolution on 16 February 2012 to express “serious concern at the situation in Hungary in relation to the exercise of democracy”, and a second resolution on 3 July 2013, based on a report drafted by rapporteur Rui Tavares.

Concurrently, the party has taken a Eurosceptic stance, depicting the EU’s expressions of concern as an undue imposition on a democratically elected majority. In a speech given on 15 March 2012, the anniversary of the 1848 Hungarian revolution, Viktor Orbán associated Hungary’s ‘freedom fight’ (szabadságharc) against the European Union to those fought against the Habsburgs in 1848 and against the Soviets in 1956. On 5 July 2013, following the EP’s discussion of the Tavares Report, the Hungarian Parliament adopted a ‘Resolution on the right of Hungary to Equal Treatment’. Reacting the same day on public radio, the Prime Minister spoke of the EU as an ’empire’ using methods comparable to those of the USSR. He declared that “since the rule of Soviet empire, no other external power has dared to try to curb the sovereignty of Hungarians openly, choosing a legal form.”

The government has also strengthened its diplomatic ties with Russia in a political u-turn for the Fidesz party. While in opposition between 2002 and 2010, they regularly accused the socialist government of pursuing pro-Russian policies. For example former socialist Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány was criticised for signing an agreement with Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin over the Southern Stream project in February 2008. Besides the current government’s continued partnership with Gazprom over the pipeline, there is mounting evidence of Fidesz’s newfound desire for alliance with Russia. Most tellingly an agreement was signed in Moscow on 14 January 2014 for two new energy blocks to be built by Rosatom, a Russian state corporation, to expand Hungary’s nuclear power plant in Paks. The project will be financed by a 10 billion euro loan from the Russian state.

Ambivalent popular support for an inconsistent discourse

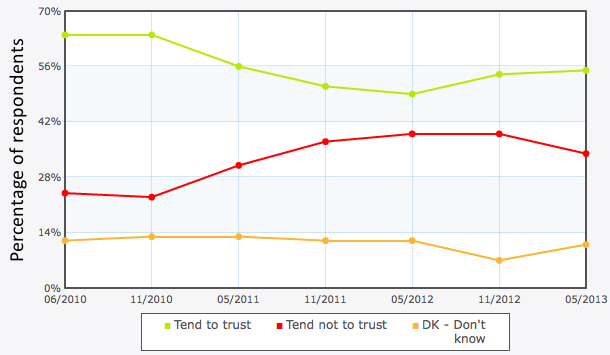

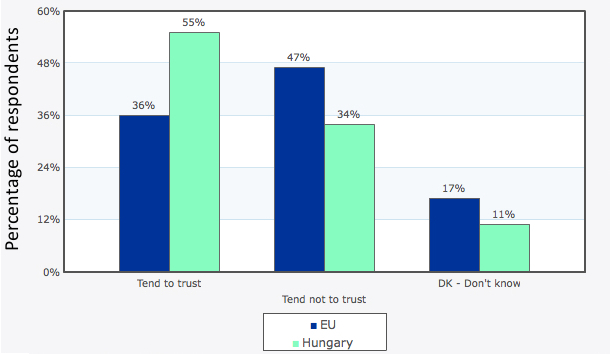

Hungary’s new geopolitical positioning has strong support among the party’s ranks, but reception among the general population is mixed. Chart 1 below shows that, according to Eurobarometer data, Hungarian respondents were more likely to express distrust towards the European Commission in 2013 than at the beginning of Fidesz’s mandate. However, this is an EU-wide trend and Hungary remains above the EU average, as seen in Chart 2.

Chart 1: Responses in Hungary to the question: “Do you tend to trust the European Commission?” (2010 – 2013)

Source: Eurobarometer

Chart 2: Comparison of responses in Hungary and the rest of the EU to the question: “Do you tend to trust the European Commission?” (May 2013)

Source: Eurobarometer

As for Fidesz’s eastern reorientation, there is little reliable public opinion survey data available, as results vary depending on the pollster’s partisan affiliation. Thus, while on 3 February 2013 the liberal Medián found only 34 per cent of respondents support a Russian deal on atomic energy, on the same day 51 per cent of those questioned by the conservative Nézöpont institute were supportive of the Paks deal.

This ambivalence may partially be explained by the inconsistencies of Fidesz’s discourse. The core of the party’s rhetoric is the association of current left-wing opposition to the past communist regime. In a speech on 23 October 2013, Viktor Orbán denounced his opponents as “those who helped the Muscovites, men in Russian type quilted jackets, red barons – depending what was in fashion”. The foreign partners of the left, in the Prime Minister’s words, have accordingly “changed their quilted jackets to suits, and tovarish to Tavares”. Thus, Fidesz defines Brussels as the new ally of the left and hence as the new enemy of the Hungarian nation.

Despite the internal logic of this discourse, professed anti-communism sits uncomfortably with a pro-Russian foreign policy. Arguably, current events in Ukraine reveal these discrepancies as emphasised by centrist-conservative blogger Véleményvezér. Comparisons between the Ukrainian situation and the Soviet Union’s suppression of the 1956 Hungarian revolution are coming in from around the world. In this context, Fidesz’s inability to criticise Russia undermines a worldview in which his party is the heir of the freedom fighters of ’56 and the left are the descendants of the regime installed by the Soviet conquerors. As Véleményvezér writes, “Viktor Orbán has freed the Hungarian left of their most important political burden”.

Foreign policy in the electoral campaign

The opposition challenging Prime Minister Orban’s party in the upcoming elections has long sought to make his turn from west to east a centrepiece of the campaign. The Unity political alliance submitted legislation to suspend or cancel the Paks agreement with Russia. More generally, Unity has moved to frame the election as a choice between Russian-style authoritarianism and Western-European liberal democracy. Gordon Bajnai, one of the leaders of Unity, promised to lead the country in a “peaceful, calm, European direction”. The ruling parties remain quiet on the matter – in contrast to their previously strong defence of the Paks agreement. Fidesz spokeman Robert Zsigo stated that the Ukranian situation should not be part of the campaign.

Recent events in Ukraine have led to some changes in the Hungarian political discourse, it remains to be seen whether and how they will affect the outcome of the 6 April elections.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: artorusrex (CC BY 2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1gKm3DI

_________________________________

Lise Herman – LSE European Institute

Lise Herman – LSE European Institute

Lise Esther Herman is a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). Her research concerns the dynamics of contemporary party politics in France and Hungary, with a specific focus on the current evolution of mainstream partisan identities in polarized party systems.

–

Johannes Wachs

Johannes Wachs

Johannes Wachs is based in Budapest and has an interest in the Hungarian and European political landscapes. He is an MSc graduate of Central European University where he studied mathematics.

“centrist-conservative blogger Véleményvezér”

What an explicit, blatant lie!

“Véleményvezér” was a team of bloggers on blog.hu.

Out of the 25 bloggers, I’d say only one could be considered “conservative”: Rajcsányi Gellért who is the editor-in-chief of mandiner.hu

http://velemenyvezer.blog.hu/2012/01/15/velemenyvezerek_a_velemenyvezeren

The rest are all so-called “left-liberal” journalists at Magyar Narancs, HVG, Index, Origó, cink.hu, 444.hu etc., that is “left-liberal” media.

“Véleményvezér” has moved to the “left-liberal” 444.hu and that’s no coincidence.

I wonder if RG still writes for Véleményvezér.

Great article, very accurate.

The fact is that Ukraine was conned into giving up its nuclear weapons and ICBM’s by the US, Russia and the UK (Budapest Memorandum) in return for the guarantee of Ukraine’s territorial integrity by these 3 powers. We now know how that turned out. Other Eastern European NATO members were also conned into disarming. Hungary was convinced to give up all of its shoulder fired anti aircraft missiles as well as hundreds of medium range rockets in return for NATO membership. Subsequently the US also convinced Hungary to transfer its Russian made tanks and helicopters to Iraq and Afghanistan. None of this equipment has been replaced and the Hungarian armed forces are in deplorable condition. Manpower is down to about 29,000 from 157,000 and there are no real reserves. There are no modern tanks like the Leopard. They have about 180 old T-72’s in storage. The Air Force has only about 12 modern combat planes. There is an almost complete lack of attack helicopters. Most of the equipment is old Warsaw Pact crap. Now the wolf is at the door and the Hungarians realize that if the Russians invade the country will be overrun in 24-72 hours and Obama will give another speech and will send MRS’s.

Do not expect Hungary to weigh in on the matter prematurely. Hungary was never part of the Soviet Union, it was a “people’s republic”. Until the Ukrainian people rise up against the Russian military like the Hungarians did in 1956; Hungary does not have as much in common with Ukraine as many of you might think.