The European Parliament elections on 22-25 May are expected to see a significant increase in support for Eurosceptic parties. Inez von Weitershausen writes that while this has been regarded by some commentators as a negative development, pro-EU politicians could also learn from the approach adopted by Eurosceptic leaders such as Nigel Farage. She argues that the one thing Eurosceptic parties have offered is a clear vision of the future of Europe and pro-EU politicians have an obligation to present the other side of the debate.

The European Parliament elections on 22-25 May are expected to see a significant increase in support for Eurosceptic parties. Inez von Weitershausen writes that while this has been regarded by some commentators as a negative development, pro-EU politicians could also learn from the approach adopted by Eurosceptic leaders such as Nigel Farage. She argues that the one thing Eurosceptic parties have offered is a clear vision of the future of Europe and pro-EU politicians have an obligation to present the other side of the debate.

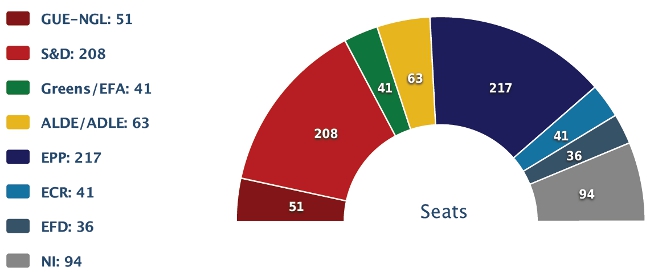

Most elections are about the question of who wins. A first look at the upcoming European Parliament elections also seems to suggest that the vital issue is whether the conservatives (European People’s Party – EPP) or the social-democrats (Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats – S&D) will “make the race” and who will thus be most likely to present the new President of the European Commission. The latest Pollwatch predictions, shown in the Figure below, indeed suggest a close race, with the EPP currently holding a small advantage of nine seats.

Figure: Pollwatch seat prediction for the 2014 European Parliament elections

Note: Pollwatch prediction from 23 April. European Parliament groups are: European United Left–Nordic Green Left (GUE-NGL); Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D); The Greens–European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA); Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE); European People’s Party (EPP); European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR); Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD). NI refers to MEPs which are not attached to any group. Visit the Pollwatch website for full predictions.

Yet the arguably much more interesting question is not whether the group of Jean-Claude Juncker (EPP) or that of his competitor Martin Schulz (S&D) receives most votes. Both are middle-aged, male, well-known and EU insiders. Rather, it will be interesting to see whether the right-wing and Eurosceptic parties, which have recently gained increasing importance at the national level, will be able to translate their influence to the European arena. In the context of the still on-going Eurozone crisis and increased doubts regarding the added value of Europe if it does not guarantee economic well-being, the vital question of the upcoming elections is hence not “who wins” but “who – and how many people – will care to vote at all?”

Parties such as UKIP, the Front National, Italy’s Lega Nord, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), Aternative für Deutschland (AfD), or Flemish Interest in the Netherlands are certainly not identical with regard to their traditions, objectives, or the extent to which they reject the idea of Europe. Nevertheless, they share an important feature: they are all able to attract a growing number of supporters with clear, simple messages, passionate rhetoric, charismatic leaders and professional organisation.

Against this background, the established and pro-European parties have to increasingly ask themselves how they can win back support for their cause. Some measures have already been taken. Europe has attempted to appear less bureaucratic and detached from its citizens. Juncker and Schulz have engaged in what could be identified as the humble beginnings of political campaigns. The parties have attempted to create more distinct images and positions for themselves, to develop an identity which crosses national boundaries and that can be communicated via campaign videos.

Yet the problem is that these steps have come late and half-heartedly, as political leaders still try to cater to two audiences at the same time: those who believe that Europe should be first and foremost a technical project, limited by national sovereignty and domestic politics, and those who believe that there is a bigger role for the EU to play. This inner conflict is not new. The ‘founding fathers’ of European integration also disagreed over how and to which objective the union should develop.

Yet the truth is that even though the Commission is not directly elected, there is no formal constitution and national interest groups remain vital actors in many policy fields, the EU is already a political reality, and its citizens form and express their opinions as they would in other elections. They react to domestic crises by punishing those who they consider responsible and by voting for those who promise them a better future. They are attracted by charismatic political leaders such as Nigel Farage, Marine Le Pen or Geert Wilders, who demonstrate passion for their cause and try to win support by mobilising all of the forces available to them. And they are no longer willing to cope with political leaders who do not sufficiently explain the added value of their project for today’s world. This is not to say that the arguments of peace and international understanding are less important today than they were nearly six decades ago, but they have to be combined with very clear messages about the costs and benefits for the European project in the 21st century.

Europe’s anti-EU parties are aware of this and have understood how to play their game: they address those topics which are relevant to their respective citizens, strategise about possible coalitions and provide voters with a clear idea of what Europe could (not) look like under their leadership: more national autonomy, fewer immigrants and a better economic position. It is time for the pro-European parties to do the same and demonstrate the other side of the coin, namely what the individual states would be left with if they gave up Europe: less global leadership in vital issues, restricted inter-cultural exchange and economies which will have to sustain themselves independently in an increasingly competitive international environment.

Juncker, Schulz and the EU’s other mainstream actors must outline, clearly and in no uncertain terms, what Europe is about, and they must listen and respond to citizens’ demands. Importantly, however, they also have to step up competition against each other in order to become more attractive for the voters who – despite widespread Euroscepticism – are willing to take part in political elections. For what is at stake is more than the question of who will win. These elections are about the future of Europe from 2014 onwards.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image credit: © European Union 2014 – European Parliament (CC-BY-SA-NC-ND-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1jaL7oB

_________________________________

Inez von Weitershausen – LSE

Inez von Weitershausen – LSE

Inez von Weitershausen is a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics.

The article fails to remark on the contex within which these unfolding events are taking place. 2008 and the crisis following has left a mark that cannot be easily erased. However much we like to think of ourselves as post industrial mature democracies the need to find a monster to blame for our pain is ever with us. What is strange is that the direction of people’s attention is toward the EU when the cause of so much economic pain did not come from the EU. In fact working togther is a route to a solution and future prosperity. Opportunist right wing politicains have jumped in and filled the media space with a mass of negative propaganda. This has fallen on fertile ground. If pro-European politicians have a problem it is getting resources togther to match the message and project a positive vision but at the same time making sure that those who brought the crisis stand accountable.

I think, to build on John’s point, one of the key problems in the EU debate is that it’s not just a normative argument about what the EU should be, it’s also an argument about what the EU actually is. The UKIP angle in this respect is that it’s a kind of dictatorship by bureaucrats, in which a clique of unelected politicians dictate no less than 75% of our laws to us. They argue that the cost of maintaining it (usually implied as consisting almost entirely of bureaucrats’ salaries or transfers to other countries) is unfeasibly large, to the extent that it actively cripples our economy.

The correct response to this isn’t to offer an alternative vision of the future, but to offer a limited correction of the various misunderstandings of the present that go toward constructing this image. In short it’s a problem that should be responded to on an educational basis rather than a political one.

If European electorates knew broadly how the EU worked, knew that the Commission did not have primary responsibility for determining legislation, had some broad idea of how much the EU budget actually costs, and understood that national parliaments still have the majority of responsibility for most major areas of policy (regardless of what raw percentage of laws we measure as coming from Brussels), then the UKIP argument would have little traction with the electorate – just as it has little traction in academia, business, mainstream politics and any other sector that directly engages with the EU on a regular basis.

None of which is to say that the EU isn’t worth criticising, or that all criticism of the EU comes from the standpoint of ignorance. It’s simply to say that part of what makes the UKIP vision of the EU so appealing is the fact that it’s largely a fantasy. It’s much easier to be up in arms about a dictatorship led by bureaucrats than it is to deal with the EU’s many real, but far more limited flaws in detail. Presenting a vision to the electorate shouldn’t come at the price of distorting the facts.

I do agree with everything that has been said here. However, I feel one key point is underemphasised. Parties like, UKIP, however shallow, will always appear as rational while the main parties are quarrelling over details. Although the bureaucracy of the EU institutions is up for debate, the raison d’être of the project has been criminally underplay by both the political elite and the mainstream media for over 20 years. The sustained peace that EU integration has established is nothing short of a miracle, particularly when compared to the destruction of the first half of the century. It appears that economics has taken over all discussion since 2008, but as the economic situation recovers should the EU discussion not return to this far more important success?

Reactionary parties, such as UKIP, will always gather some element of support, particularly as they provide great entertainment value and pitch themselves as being a rebellious alterative to the squabbling we are used to seeing. However, when held up against the most righteous of EU ideals, their defensive arrogance withers. It is this which will remind people of the success of today and the horrors of the past. I do feel for Nick Clegg, is as much as he has been the only politician (since the ERM exit) willing to risk public backlash but putting the case for the EU. Perhaps it is because his image has already been tarnished, he has the freedom to make this case. It is to the shame of the other main parties that they fear and distrust the UK electorate so much that they dare not suggest how good we have it at the moment, within the EU. Details of fiscal policy and legislation aside, someone needs to get across to the UK public just what reality could look like had the EU project not been started.