In the aftermath of elections in April, several political parties in Macedonia, including the main opposition party, the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM), have refused to take up their parliamentary seats amid accusations of electoral fraud. Goran Janev writes that while the record of the ruling VMRO-DPMNE party in government has raised legitimate democratic questions, the strategy being pursued by the opposition is unlikely to be successful. He argues that what the country really needs is clearer guidance from external actors, most notably those within the EU.

In the aftermath of elections in April, several political parties in Macedonia, including the main opposition party, the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM), have refused to take up their parliamentary seats amid accusations of electoral fraud. Goran Janev writes that while the record of the ruling VMRO-DPMNE party in government has raised legitimate democratic questions, the strategy being pursued by the opposition is unlikely to be successful. He argues that what the country really needs is clearer guidance from external actors, most notably those within the EU.

The recent parliamentary and presidential elections in Macedonia have once again proven the strength of populist politics. The rise of populist parties across Europe contradicts the promise of the European project, as both inside and outside of the EU, ‘big ideas’ no longer appear to hold appeal for ordinary citizens. Whether the focus is on Communism, solidarity, or one Europe, these ideas are seemingly too big for Europeans to accept.

If the recent financial crisis and fears over immigration are to be held responsible for the rise of populism in EU countries, a perpetual economic crisis and weakening prospects for joining the EU have had the same effect in Macedonia. With the long wait for a better future proving tiresome for the majority of citizens, Macedonians have instead chosen as their champions those who promise smaller goals. The ruling nationalist right-wing conservative party, the VMRO-DPMNE (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization – Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity) has consequently won every election since 2006: twice the presidential, twice the local, and four times the parliamentary elections.

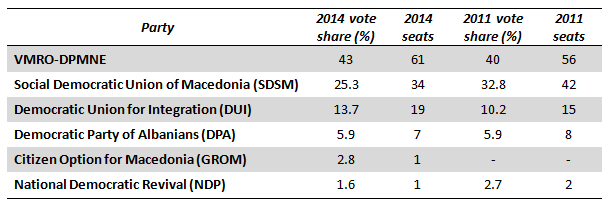

One way or another, in the 2014 elections, amid allegations of intimidation, the ruling party received around 43 per cent of the vote, with the opposition Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM) only gaining around 25.3 per cent. Translated into parliamentary seats, VMRO-DPMNE emerged with 61 seats, and SDSM only 34 – a loss of 8 seats from the total they achieved in the last Macedonian parliamentary elections in 2011. The Table below shows these results.

Table: Results of the 2014 Macedonian parliamentary elections

Note: Vote shares rounded to one decimal place. For more information on the parties see: VMRO-DPMNE, Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM), Democratic Union for Integration (DUI), Democratic Party of Albanians (DPA), Citizen Option for Macedonia (GROM), National Democratic Revival (NDP). Source: SEC

Faced with this outcome, SDSM opted for radical steps in response. The party refused to take up the parliamentary seats they had won in the election, exacerbating the existing political problems within Macedonia and pushing the situation toward a wider institutional crisis.

In doing so, SDSM’s aims have been firmly pinned to the potential for help to come from outside as they are unable to garner sufficient political support at home. The hope is that the international reaction will take their side in the dispute and that this external pressure will act to delegitimise the ruling party, resulting in new elections organised by a technical government with tight control and monitoring from international actors. It is difficult to believe that this will happen.

For the last 8 years, VMRO-DPMNE has enjoyed unwavering popular support while, paradoxically, the arguments against them have grown. Poverty within Macedonia remains unaddressed, social and economic inequalities have grown at a rate far beyond most states in the region, and the country’s unemployment problem ranks as one of the worst in Europe. Meanwhile, measures of press freedom have steadily declined each year and the courts are among the least trusted institutions in the country. Yet despite these trends, the election results have legitimised the government’s policies and actions.

The country’s disorganised opposition has yet to emerge fully from the legacy of the remarkable Machiavellian character, Branko Crvenkovski. Crvenkovski, who served as Prime Minister three times and as President once, still casts a long shadow over SDSM, the party he led for two decades from independence until 2013. This long reign has left SDSM deeply divided between his lifelong supporters and those who look toward new leadership. Extricating themselves from the ghosts of the past is made all the more difficult by the fact that VMRO-DPMNE insists on adopting anti-communist rhetoric, alongside a personalised form of politics which projects all ills on to the figure of Crvenkovski.

Far more worrying than the predictable voting patterns, however, are the authoritarian tendencies that have become more visible after each VMRO-DPMNE electoral victory. Since the party’s ascension to power, every possible mechanism has been set in motion to strengthen VMRO-DPMNE’s hold over society. Over the course of the last 8 years, they have successfully managed to spread their influence from executive positions to other sectors which, from a democratic perspective, should remain independent, notably the media and judicial institutions.

Moreover, the subjugation of government apparatus and dependent sectors in society via so called ‘patronage’ has taken place under the party’s rule. Indeed, this is the only logical effect when the largest economic resource at the disposal of Macedonian citizens is employment in the administration. Such advancement does not require initial capital or a business plan, all it takes is connections with those in power. Those outside of the bureaucracy seek contacts and good relations with the ruling party, ensuring that public procurement and business regulations can never be completely neutral.

The most prominent indicator of those dangerous authoritarian tendencies has been the development of a system of selective justice. Nikola Gruevski, Macedonia’s longest serving Prime Minister, has lived up to even the most cynical of expectations since coming to power, with several questionable arrests of opponents. Tax fraud, bribery, corruption and other offences have been used to sanction these arrests over the past five years. The profile of those imprisoned ranges from the leader of a political party, to the owner of a media organisation, a journalist, the president of a local council, and the leader of an independent union. This intimidating pattern has wide resonance in a society with poorly developed democratic institutions: a country where party control has been the prevailing paradigm for the last seven decades, not simply the last eight years.

All of these factors taken together, the conclusion could be reached that political culture in Macedonia is still yet to fully mature – or even meaningfully develop – since the collapse of communist rule more than two decades ago. The ruling party has effective control over the executive, judicial and legislative institutions, and over the media. Economic prosperity feeds through largely to those who are well connected to the state apparatus and those who control it. Therefore, political pluralism has failed to deliver democratic rule. Indeed, the appearance of political pluralism essentially acts as a shield for the continuation of a one-party regime.

SDSM’s attempt to involve the international community by provoking a political crisis might have yielded some results if the EU and the United States had the will to become involved in Macedonian affairs. However the on-going name dispute with Greece has demonstrated western indifference toward the country. Gruevski is still some distance from proclaiming the kind of ubiquitous political support associated with a dictatorship and Macedonia is still far from a priority for western politicians.

The establishment of an enthnocratic regime in Macedonia capable of pacifying the aftershocks from the situation in neighbouring Kosovo provided some short-term peace of mind for the international community. However it also helped to entrench patriotic and nationalist discourse as the most secure political currency within Macedonia itself. VMRO-DPMNE has capitalised on this by attacking perceived domestic and foreign enemies, suggesting that Macedonians remain safer under their protection. The party’s Albanian counterparts have mastered a similar strategy, forming a productive symbiosis with Macedonian nationalists.

The real hope is that from this endless transition and perpetual crisis, grassroots activism can reawaken among those generations born to an independent Macedonia, who can no longer relate to the myths of ‘evil’ communists, Macedonians, or Albanians, and instead seek to find solace in an open and connected world. This could be aided by actors within the European Union who, rejecting the notion that the European project should be abandoned, are prepared to send a clear signal that a democratic Macedonia is a welcome future member of the club.

But a prerequisite for the EU helping Macedonia to overcome its problems with populist politics will be for Europe to succeed in breaking with its own populist threat. Macedonia can only internalise European values by following the EU’s lead and this requires that EU states start embodying these values, rather than merely articulating them. Macedonian accession may be the perfect test for this principle.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image credit: Jaime Pérez (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/QE6VOx

_________________________________

Goran Janev – Sts Cyril and Methodius University Skopje, Macedonia

Goran Janev – Sts Cyril and Methodius University Skopje, Macedonia

Goran Janev was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Goettingen, working on “Manipulating diversity in South-East Europe”. He completed a D.Phil in Social Anthropology at the Institute for Social and Cultural Anthropology, Oxford University. His research interests include political anthropology, ethnicity, human rights, multiculturalism, governance and public space.

Pretty good essay but it missing something important… VMRO promoting an “ancient Macedonian” identity and irredentism against Greece.

Until this “Macedonian” identity issue is resolved (in an honest manner rather than evasive fashion) there will be no progress in name dispute. There are millions of Macedonians (of the Greek varierty) south of the former Yugoslav republic who continue to exist even the entire world downplays the now obvious state propaganda in FYROM (patronizing evasion that only fuels xenophobia in Greece). In addition, ancient Macedonian artifacts will forever be written in Greek even if Greeks disappear off the face of the earth.

Resolving the issue requires moderates in FYROM having the courage to take a different name and distance their identity from antiquity. Anything less will lead to perpetual instability in the Balkans.

‘