Ukraine is due to hold the first round of voting in its presidential elections on 25 May. Max Bader assesses the main candidates in the election, the likely result based on opinion polling, and what the outcome might mean for the wider Ukraine crisis. He notes that there is very little doubt about who will win the contest, with Petro Poroshenko currently polling substantially higher levels of support than any of the nearest challengers, including in the country’s eastern and southern regions. However while this provides some hope that the election could help de-escalate tensions within Ukraine; the lack of participation of voters in Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk could potentially undermine the legitimacy of the result.

Ukraine is due to hold the first round of voting in its presidential elections on 25 May. Max Bader assesses the main candidates in the election, the likely result based on opinion polling, and what the outcome might mean for the wider Ukraine crisis. He notes that there is very little doubt about who will win the contest, with Petro Poroshenko currently polling substantially higher levels of support than any of the nearest challengers, including in the country’s eastern and southern regions. However while this provides some hope that the election could help de-escalate tensions within Ukraine; the lack of participation of voters in Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk could potentially undermine the legitimacy of the result.

Held against the backdrop of a recent revolution, territorial loss, and separatist conflict, the presidential election in Ukraine on 25 May is the most anticipated in the country’s brief history as an independent state. The intrigue in the election, however, is not so much about who will win, but about three interrelated questions: first, where will the election take place? Second, who will accept its outcome? And third, how will its outcome affect the political and security crisis in the country?

The candidates

For a country that is known to be divided, it is surprising how little doubt there is about who, among the nearly two dozen candidates, will win the election. According to recent polls, some forty per cent of decided voters will cast their vote for Petro Poroshenko. Considering that his support is on the rise, Poroshenko may well win in the first round, which would save the country a number of weeks of uncertainty about who will become the next president.

Poroshenko has become the frontrunner candidate despite being one of the country’s oligarchs, who have corrupted the political process in Ukraine over the past twenty years by using politics to promote their business interests. Poroshenko is seen first and foremost as a pragmatist (he was even a short-time cabinet minister during the Yanukovych years) who may possess the acumen and natural authority to stabilise the country.

The other main candidate from the former opposition, Yulia Tymoshenko, is seen by many as part of the problem of the ‘old politics’ which led to the Euromaydan Revolution, rather than the solution. Tymoshenko’s fall from grace is especially remarkable because she was close to winning the presidential race against Yanukovych in 2010, and because she was the most prominent political prisoner of the country from 2011 until the revolution.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are no candidates who represented the Yanukovych regime and who now wield mass support in the southern and eastern regions of the country. According to polling data, support for the candidate of Yanukovych’s Party of Regions, Mikhail Dobkin, stands at less than five per cent.

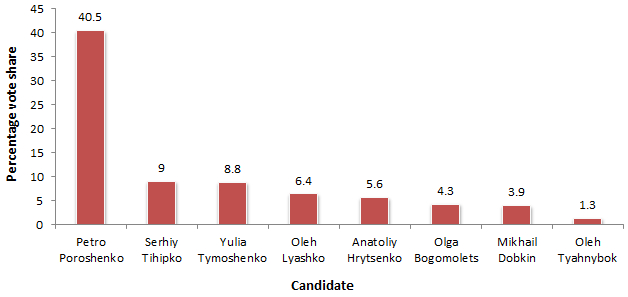

Finally, it is noteworthy that the nationalist candidates will only play a marginal role in the presidential race. Kremlin propaganda has it that the Right Sector, one of the organisations that was at the forefront of the Euromaydan Revolution, now practically runs the country. Support for its candidate in the elections, Dmitro Yarosh, however, is below one per cent. The other nationalist candidate, Oleh Tyahnybok of the Svoboda Party, scores only slightly better. The Chart below shows the results from one of the most recent polls, conducted on 6-8 May.

Chart: Predicted vote shares for 2014 Ukrainian presidential election

Note: Figures are from polling conducted by GFK on 6-8 May. The percentages include don’t know/refused responses which amounted to 15.4 per cent and which have been left off the Chart. All candidates who received less than one per cent have also not been included in the Chart. In addition, figures for the Communist Party of Ukraine’s candidate, Petro Symonenko, have not been shown as he has withdrawn from the contest since the poll was conducted (he received 2.7 per cent in the poll). For more information on these candidates see: Petro Poroshenko (independent); Serhiy Tihipko (self-nominated – was expelled from Party of Regions); Yulia Tymoshenko (Batkivshchyna); Oleh Lyashko (Radical Party); Anatoliy Hrytsenko (Civil Position); Olga Bogomolets (independent); Mikhail Dobkin (Party of Regions); Oleh Tyahnybok (Svoboda).

Which regions will be able to vote?

A week before the election, it is still unclear whether the vote can take place in parts of the country’s two eastern-most regions. What is clear is that few permanent residents of Crimea, annexed by Russia following the Euromaydan Revolution, will be able to vote. Ukraine now faces a dilemma long known to other ex-Soviet republics such as Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Moldova, who equally do not control part of their territory: how to organise an election when part of the electorate is physically barred from voting?

Kyiv has made arrangements so that Crimeans can vote in polling stations outside Crimea, but it seems unlikely that many will undertake the effort. For Kyiv this means that five per cent of what it considers to be the country’s electorate are effectively shut out from taking part in the elections. In the eastern Donetska and Luhanska Oblasts, separatist forces continue to occupy government buildings in a number of cities. This makes it difficult if not impossible to carry out the necessary preparations for election day, let alone to organise the voting and counting process.

Limitations on participation in the eastern-most regions of the country are one of the factors that could undermine the legitimacy of the vote. If, in addition to Crimea, all of the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts would stay out of the election, some twenty per cent of the electorate would be effectively disenfranchised. To avoid this, the central authorities, with the help of loyal regional and local authorities, will do everything in their power to make sure that the election will take place in as many localities in Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts as possible. It is anyone’s guess, however, how many of the roughly 4,000 polling stations in the two regions (out of some 33,000 polling stations nationwide) will be open on election day.

The wider significance of the election

Another crucial question is whether Moscow will recognise the outcome. Moscow’s recognition would potentially pave the way toward a de-escalation of the tensions between Russia and Ukraine, and probably also prove essential in solving the separatist conflict in Ukraine’s eastern regions.

Russian official discourse has, in the past few months, consistently portrayed the post-revolution authorities in Kyiv as coup leaders and the presidential election as illegitimate because, in Moscow’s view, Yanukovych was removed from power through extra-constitutional means. On 7 May, Putin surprised many, however, by calling the presidential elections a ‘step in the right direction’. Considering the many unpredictable actions of the Russian authorities in recent months, however, few would be certain that this means that Moscow will recognise the outcome of the elections.

There are many reasons altogether to await the election with trepidation and concern. On the other hand, the election could also mark a turning point in Ukraine’s misfortune. Especially if the new president is elected in the first round, with broad cross-national support, and with Moscow’s approval, this may take the steam out of the separatist movement in the East.

Another reason why the election could have beneficial effects has to do with the dynamics of the presidential race. Particularly since the beginning of the century, the regional divisions in Ukraine have been sharply reflected in electoral outcomes. In the 2004 Orange Revolution which brought Viktor Yushchenko to power, for example, his contender Viktor Yanukovych was still supported by a vast majority of voters in the East and South of the country in the third and final round of the election. Polling data in recent weeks, however, show that Poroshenko is currently the leading candidate in all four core geographical regions of the country (West, Centre, East, and South). Paradoxically, then, while the country is currently strained by separatist conflict and increasing tensions, the election could help to bring the different parts of the country closer together.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/TlEZRI

_________________________________

Max Bader – Leiden University

Max Bader – Leiden University

Max Bader is Assistant Professor of Russian and Eurasian Studies at Leiden University. He will serve as a short-term observer in the upcoming presidential elections in Ukraine.