On 27 June, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine signed co-operation agreements with the EU. Ellie Knott assesses what the agreements mean for each state and how they might influence future EU-Russia relations. She writes that while the agreements are largely technical in nature, their real value is symbolic as they represent a final break from each country’s Soviet past. She argues that with tensions already high over the Ukraine crisis, the agreements will also have a significant impact on the wider relationship between the EU and Russia.

On 27 June, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine signed co-operation agreements with the EU. Ellie Knott assesses what the agreements mean for each state and how they might influence future EU-Russia relations. She writes that while the agreements are largely technical in nature, their real value is symbolic as they represent a final break from each country’s Soviet past. She argues that with tensions already high over the Ukraine crisis, the agreements will also have a significant impact on the wider relationship between the EU and Russia.

Since the Vilnius summit in November 2013, relations between the key Eastern Partnership states (Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia), the EU and Russia have shifted inextricably. The EU has sped up its signing of Association Agreements (AA) and Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTA) with Georgia and Moldova, and held on to its commitment to sign these agreements with Ukraine, with the official signing of these agreements with all three states taking place on 27 June.

Meanwhile, Russia’s willingness to challenge Ukraine’s territorial integrity, by seizing Crimea, its tenuous relations with separatists movements in Donetsk and Lugansk and its cessation of gas exports to Ukraine, have drastically changed not just the configuration of the Ukrainian state and society, but have been one of the biggest earthquakes for relations between Russia and the wider post-Soviet region.

The key question remains: why should Russia be concerned with what are essentially 1,000 page technocratic documents between Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia and the EU? As Herman Van Rompuy, President of the European Council, continues to argue, there is “nothing in these agreements, nor in the European Union’s approach, that might harm Russia”. Van Rompuy has been careful to use rhetoric that argues that this is not a “zero-sum game”: Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia are free to have relations with Russia to whatever extent they choose, except becoming members of the Eurasian Customs Union.

To Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia, signing such agreements with the EU might not be a zero-sum game, and in fact the biggest challenge will be how to maintain relations with Russia. Yet in the way that the leaders of Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova welcomed the signing of the AA and DCFTA with the EU, it is clear that these leaders do consider the agreements to be decisive in how they situate themselves geopolitically. In an interview with CNN, the new Ukrainian President, Petro Poroshenko, remarked that “this is a civilisation choice. This is the Rubicon – when we crossed the Rubicon to Europe and left in the past our Soviet past”.

The Association Agreements are therefore not just political and economic documents but, as Poroshenko described, a “symbol of faith” and “unbreakable will”. Moreover, these agreements are considered to be the first step in a journey towards, as Iurie Leancă the Moldovan Prime Minister states, their “primordial/essential objective” towards becoming a “full-fledged member of this great family of the European Union”. For Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia, their more formalised relationship with the EU, and the hope that this might one day be converted to membership, is more than about technocratic documents, but about being recognised as European, in status, rights and identity, and about no longer being seen as a former Soviet republic.

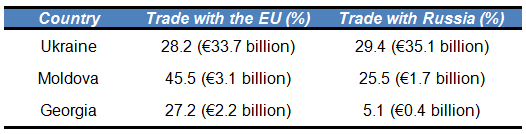

However the beginning of this journey of closer political and economic association with the EU, and the opening up of the free trade potential, is also the continuation of substantial uncertainty regarding how this will affect their relations with Russia. Russia is a significant trading partner for all three states, and in particular for Ukraine where Russian imports and exports exceed those of the EU. As the Table below shows, Russia is still an important trade partner for Moldova, though less for Georgia. All three states have been exposed to Russian embargos on goods, and Georgia, and more recently Moldova, have learned the importance of diversifying who they trade with.

Table: Percentage of foreign trade with the EU and Russia in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine

Note: The Table shows the value of exports and imports between each country and Russia/the EU, and the percentage of total trade which the EU and Russia account for in each case. Figures are from European Commission trade statistics for Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia

All three states have energy requirements which are not just dependent on Russian gas, but also on the cheap price of this gas. In Ukraine, residential customers have paid only about 25 per cent, and industrial consumers only 75 per cent, of what the gas would be worth on the European market. It is unlikely, whatever the outcome of the current Ukrainian-Russian gas crisis, that any deal going forward will lead to significant increases in this price.

This will be augmented by Ukraine’s loss of the Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol. Russia had agreed a lease with Ukraine for the naval base in Sevastopol which was key in negotiations over a reduced gas price and which Ukraine had used to offset the country’s debt to Russia. However, following the annexation of Crimea, Russia tore up the Kharkiv accords, which extended Russia’s lease to 2042, and which Ukraine can no longer use as a way to offset their Russian debt, the payment of which, in addition to Russia’s move to increase the cost of gas, are key to areas of contention in the 2014 crisis. Gazprom, too, has shown itself to be reflective of Russia’s territorial claims, given that the map they showed at their AGM included Crimea within Russian territory.

Russia also has high leverage over Georgia and Moldova’s energy market. In the case of Moldova, their market is dominated by Gazprom and MoldovaGaz, of which Gazprom hold the majority of shares. Even attempts to diversify Moldova’s energy dependency via the construction of the Iasi-Ungheni pipeline are unlikely, even in the best case, to provide more than a third of Moldova’s gas needs, and perhaps only 5-10 per cent.

In the energy sector, there is little the EU can do to assist these states’ dependence on cheap Russian gas. Many EU member-states are themselves dependent on Russian gas and those who receive their gas via pipelines through Ukraine are particularly vulnerable in the current crisis. The EU finds itself also in a tense situation with Russia over its right to reverse the flow of gas via Slovakia to service Ukraine’s lack of energy, which Gazprom’s CEO, Alexei Miller, claims is a “semi-fraudulent mechanism” because “this is Russian gas”.

A second area of contention regards the proposed South Stream pipeline which is designed to “diversify gas export routes and eliminate transit risks” by bypassing Ukraine, running through the Black Sea to Bulgaria, and on to Central and Southeast Europe. The European Commission has warned Bulgaria not to go ahead with the project, which severely destabilised the current Bulgarian administration and will lead to early elections being held in October.

Beyond energy dependence, there is also the ongoing threat of territorial instability. Georgia, Moldova and, now and most prominently, Ukraine all have territorial contentions with Russia. This uncertainty and instability gives Russia leverage from the perspective of knowing that states remain paranoid about future incursions, while Russia knows also that there are limits to how far these states can progress with Europeanisation while these territorial questions remain. Indeed, Moldova and Transnistria still need to resolve whether the latter will be a part of Moldova’s Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement with the EU or not. Poroshenko has argued that Crimea is part of Ukraine’s agreement with the EU and that without the return of Crimea, “normal” relations between Ukraine and Russia will not be possible.

This year will be remembered in Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia as a year in which their relationship with the EU altered dramatically with the formalised signing of the Association Agreements and Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements. In the case of Ukraine, it will be remembered also as the year of “revolution of dignity” which led also to an unfathomable deterioration in Ukraine’s relations with Russia, and as a year in which Ukraine’s right to govern Crimea, and parts of Donetsk and Lugansk, began to face an unprecedented challenge.

These are challenges that Georgia and Moldova have faced since the beginning of the post-Soviet period. The EU must realise that even if it does not pitch itself to be in competition with Russia, this is a naive position which ignores the extent to which Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia, at least symbolically, see Europeanisation as reversing ‘Sovietisation’, and as a decoupling of their centre-periphery relations with Russia, in favour of a new centre-periphery relationship with the EU. The question now is how these states’ relationships with the EU and Russia, and their own citizens too, can be managed, and in turn how the EU can manage its relationship with Russia.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1iRDLsz

_________________________________

Ellie Knott – London School of Economics

Ellie Knott – London School of Economics

Ellie Knott is a PhD candidate in the Department of Government at LSE researching Romanian kin-state policies in Moldova and Russian kin-state policies in Crimea. She tweets @ellie_knott

1 Comments