Policies toward nuclear energy vary considerably between European states, but what factors explain why different countries adopt different approaches? Using Eurobarometer data, Fabio Franchino writes on the social bases underpinning nuclear energy policies. He shows that elements such as ideology and the proximity of individuals to power plants have different effects on nuclear attitudes across Europe, which may provide an explanation for the varied policy trajectories of European countries.

Policies toward nuclear energy vary considerably between European states, but what factors explain why different countries adopt different approaches? Using Eurobarometer data, Fabio Franchino writes on the social bases underpinning nuclear energy policies. He shows that elements such as ideology and the proximity of individuals to power plants have different effects on nuclear attitudes across Europe, which may provide an explanation for the varied policy trajectories of European countries.

In April, the Japanese government approved a plan backing nuclear power again, reversing the previous government’s decision to phase it out. These U-turns are common. After the Fukushima accident, the German government scrapped an extension of its programme and shut down eight reactors. In Italy, a plan to restart nuclear power was rejected in a referendum, while the Swiss government abandoned programmes to build new reactors. Yet, in Britain, similar projects seem to have only been delayed, but not altered. Four reactors are still under construction in Europe – two in Slovakia, one in France and one in Finland.

Europe indeed offers the full gamut of policies toward nuclear energy, from constitutional ban (Austria) to cagy adoption (Germany) and enthusiastic endorsement (France). In a recent work, I have used eleven Eurobarometer surveys, conducted between 1978 and 2008 and involving more than one hundred thousand Europeans, to analyse the social bases underpinning these policies. Figure 1 shows the percentage of Europeans that considers nuclear energy unacceptably risky. The rectangular boxes and vertical lines illustrate the dispersion across the mean values.

Figure 1: Attitudes across Europe on the risk posed by nuclear energy (1978-2008)

Note: Figures are from Eurobarometer. The number of countries listed at the bottom of the chart refer to the European countries which were included in each Eurobarometer survey (which has increased as the number of EU member states has grown).

The share of respondents rejecting nuclear energy unsurprisingly increased after both the Three Mile Island and the Chernobyl accidents. In the following twenty years, it gradually shrunk, but cross-country variation remained higher than in the pre-Chernobyl period, indicating different public opinion trajectories (the patterns are similar if we limit the analysis to the nine countries surveyed in 1978). Five years after Chernobyl,attitudes have settled back to the pre-1986 values in some countries but not in others.

Left-right ideology, proximity to a plant and attitudes to risk

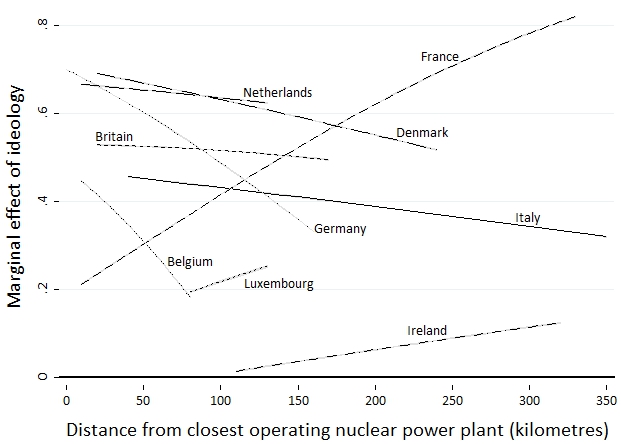

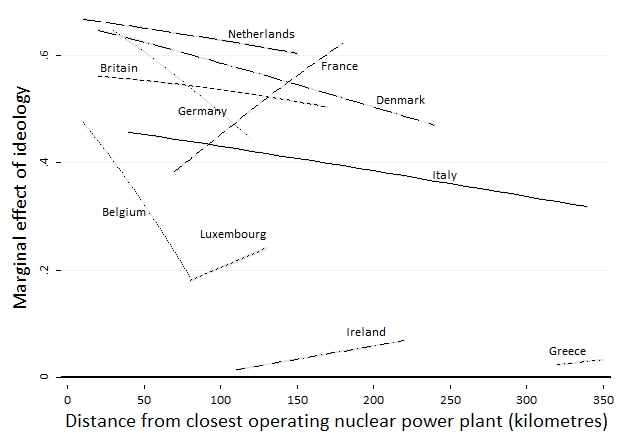

Next, I investigated how the ideological predisposition of respondents interacts with the proximity of an individual’s residence to a plant in explaining risk attitudes. Figure 2 shows the effect of a left-ward shift in the ideology of respondents on the likelihood of rejecting nuclear energy, for individuals residing at an increasing distance from a plant.I have chosen the representative years 1978 and 1982, before and after the Three Mile Island accident, 1986, a few months after the Chernobyl disaster, and 1996, ten years after the accident (more below for the 2006 and 2008 surveys).

Figure 2: How the effect of a leftward shift in ideology on attitudes toward nuclear power changes with the proximity of respondents to a nuclear power plant

[fusion_tabs layout=”horizontal” backgroundcolor=”” inactivecolor=””]

[fusion_tab title=”1978″]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”1982″]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”1986″]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”1996″]

[/fusion_tab]

[/fusion_tabs]

Note: Click on the tabs at the top to scroll through each year. For a more detailed explanation of each chart see the author’s longer journal article.

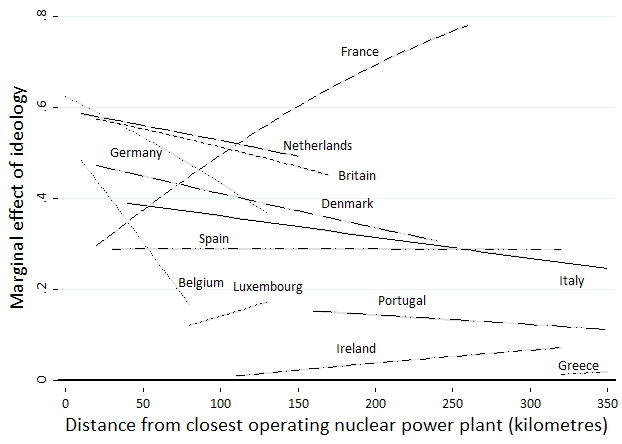

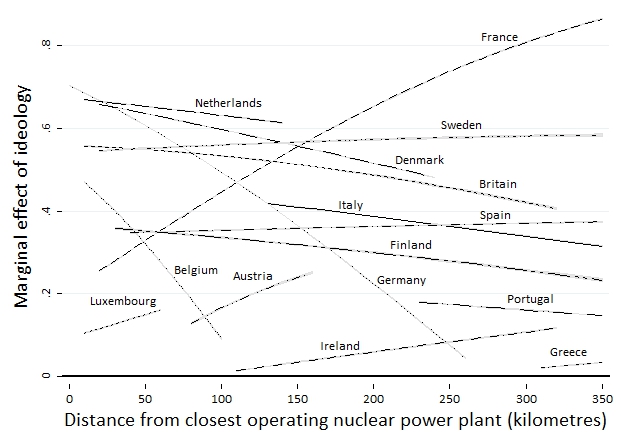

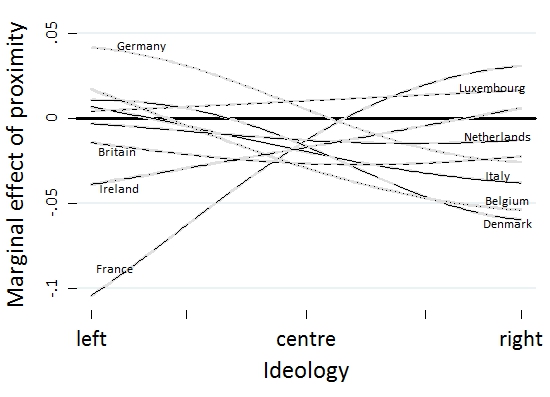

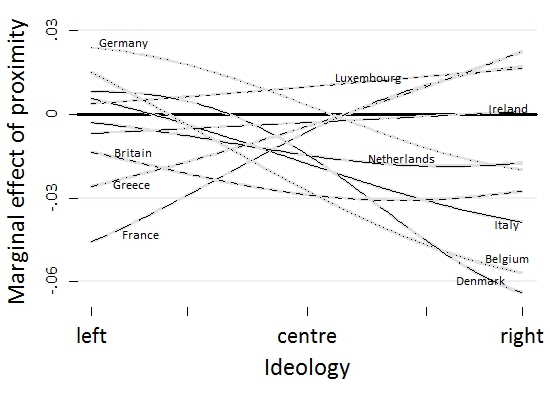

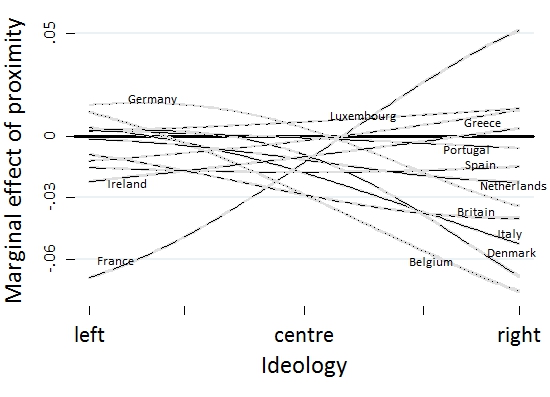

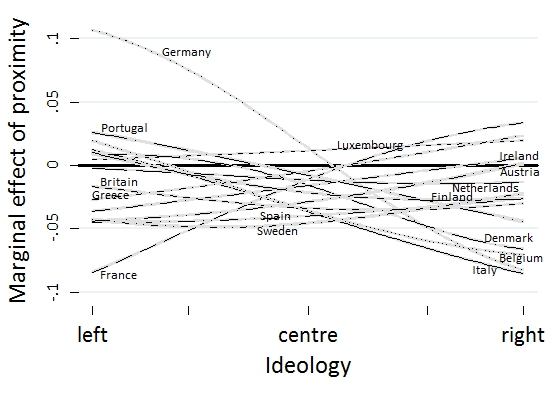

Figure 3 instead shows the effect moving closer to a plant has on the likelihood of rejecting nuclear energy, for individuals reporting different ideological views.

Figure 3: The effect of increased proximity to nuclear power plants on attitudes toward nuclear power across the ideological spectrum

[fusion_tabs layout=”horizontal” backgroundcolor=”” inactivecolor=””]

[fusion_tab title=”1978″]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”1982″]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”1986″]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”1996″]

[/fusion_tab]

[/fusion_tabs]

Note: For a more detailed explanation of each chart see the author’s longer journal article.

These figures look difficult to interpret but the main results are straightforward. Left-wing respondents are more likely to reject nuclear energy than right-wing ones, while greater proximity does not lead unequivocally to more rejection (both results are well-known in the literature). Greater proximity actually leads to more support in the Netherlands, Britain, Spain and Sweden. Instead, in Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Italy, Finland and Portugal, proximity operates as a wedge separating left- from right-wing respondents; the former becomes even more critical, the latter more favourable. In other words, ideology becomes an increasingly important component of risk attitudes.

Finally, in France, Austria, Ireland and Greece, as left-wing individuals move closer to a plant, they are less likely to reject nuclear energy. As right-wing subjects do so, they are more likely to reject it. However, since the former effect is significantly larger that the latter, proximity alleviates the conflict between supporters and rejectionists, and ideology becomes less important.

Ideology and the impact of accidents on attitudes to risk

I have also investigated how risk attitudes of different types of respondents have changed after major accidents (it should be noted here that we do not have panel surveys, but the data nevertheless offer the opportunity to evaluate how attitudes to risk change for typical respondents). According to a well-established finding in social cognition, individuals are likely to accept at face value new evidence that confirms their prior beliefs, while they subject disconfirming evidence to critical evaluation. Right and left-wing individuals, holding stronger views about nuclear energy, should therefore be less likely to change them in the face of an accident, while the views of centrist respondents, which are less entrenched, should be more volatile.

Indeed, this is exactly what we find in all the countries that have or have had nuclear energy, especially in the proximity of a plant. France represents however a notable exception. Leftist subjects actually display the highest volatility, meaning that their anti-nuclear attitudes are rather shaky. In the remaining countries (none of which have ever had nuclear power), the anti-nuclear views of left-wing respondents are the most stable; those of rightist subjects the most volatile.

The social bases to European governments’ policies on nuclear energy

This analysis allows us to paint an interesting picture of the broader social constraints within which governments operate, shedding some light on the policy trajectories of different countries. For instance, the flips and turns in the Belgian, German and Italian policies may be related to the particularly entrenched views of left- and right-wing individuals and the increased polarisation in the vicinity of plants. Moreover, volatile pro-nuclear views of right-wing individuals may be behind the inability of Italian governments to sustain a nuclear policy.

Despite well rooted opinions in the Netherlands, Spain and Britain as well, these governments may encounter fewer obstacles perhaps because their publics are more supportive overall, especially in the proximity of power stations. France is indeed unique. Its governments enjoy a pretty cushy life. Not only proximity alleviates the divergence of opinions, but the anti-nuclear attitudes of left-wing individuals look very shaky. French nuclear power policy relies on the comparatively more supportive views of left-wing individuals living close to plants.

Finally, the publics of the remaining countries (with no nuclear energy) display features that are the mirror image of France’s. The pro-nuclear views of right-wing individuals are precarious, while anti-nuclear views are solidly established in the left-leaning public. These governments also face an increasingly either polarised or rejectionist public opinion in the vicinity of plants.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image credit: mbeo (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1k5vmSV

_________________________________

Fabio Franchino – Università degli Studi di Milano

Fabio Franchino – Università degli Studi di Milano

Fabio Franchino is Professor of Political Science at Università degli Studi di Milano (University of Milan).