Jean-Claude Juncker’s new European Commission officially entered office on 1 November. Arndt Wonka and Holger Döring write on the political profile of the new Commissioners, noting that in line with the growing politicisation of the institution over recent decades, the 28 members include a record share of former prime ministers and deputy prime ministers. The percentage of Commissioners who have a partisan affiliation with their country’s current government, and the percentage who have previously gained ministerial experience in national politics, are also at record levels in comparison to previous Commissions.

Jean-Claude Juncker’s new European Commission officially entered office on 1 November. Arndt Wonka and Holger Döring write on the political profile of the new Commissioners, noting that in line with the growing politicisation of the institution over recent decades, the 28 members include a record share of former prime ministers and deputy prime ministers. The percentage of Commissioners who have a partisan affiliation with their country’s current government, and the percentage who have previously gained ministerial experience in national politics, are also at record levels in comparison to previous Commissions.

The new Juncker Commission took office on 1 November. The new Commission is exceptional at least with regard to the extent to which its appointment was covered by the media. This media attention is the result of the European Parliament’s (EP) success in politically capitalising from two limited changes in the appointment rules brought about by the Lisbon Treaty. First, the EP ‘elects’ the Commission President instead of giving consent to him in the first round of appointment; and second, governments are asked to take into account the European Parliament election results when selecting their candidate President – and the fact that the European party federations nominated so called ‘Spitzenkandidaten’ for the President’s office before the EP elections. However, the relatively strong political attention received by the Commission appointment process should not be mistaken for a fundamentally different political quality of the newly appointed Commission. Do the political qualities of the newly appointed Commissioners differ fundamentally from those of the past?

The Juncker Commission’s political profile

Since 1985 the Commission’s political profile has been sharpened, because governments have increasingly selected and appointed party political heavy-weights who have held high level political positions in their countries before taking up their post as Commissioners. The Commissioners of the Juncker Commission confirm the strong political profile of the European Commission’s political leadership. Commissioners of the newly appointed Commission are career politicians with experience in national executive leadership positions and as members of their country’s parliaments. The share of former prime ministers (four) and deputy prime ministers (two) in the new Commission is exceptional.

The appointment of new Commissions has regularly been a contested political issue because of the European Commission’s prominent place in EU politics and policy-making. Over time, governments have increasingly recognised the Commission’s political importance by nominating Commissioners who share their party political preferences, and by selecting individuals whose loyalty and skills could be assessed on the basis of political positions (ministers, MPs) which they had held before their appointment to the Commission.

As shown in Chart 1 below, since the appointment of the Prodi-Commission in 1999, roughly 80 per cent of Commissioners have been members of one of the governing parties. As Chart 1 also shows, the share of professional technocrats without a partisan affiliation and without a party political profile, who often dominated the early Commissions, has stayed at about 5 per cent during the last three decades. The Juncker Commission reinforces this pattern: no technocrats have been appointed, while the share of Commissioners who are politicians from one of the nominating governing parties has risen to an unprecedented 90 per cent.

Chart 1: Partisan links of European Commissioners to member state governments (1958 – 2014)

Note: The black line shows the percentage of Commissioners in each Commission who were affiliated to the governing party in their own country. The blue line shows Commissioners who were not affiliated to any political party, while the other line shows Commissioners who were affiliated to the opposition party within their country. The name of the Commission President of each Commission is shown in the horizontal axis, with the date the Commission was in office and the number (N) of Commissioners within the Commission at that time.

Moreover, the European Commission’s profile as the EU’s core political executive has been strengthened by the nomination of Commissioners who previously held ministerial and prime ministerial posts in their home country and thus are experienced in leading large executive administrations. Over time, the smaller member states in particular have sent political candidates with more senior positions in national executives, such as high profile ministerial experience.

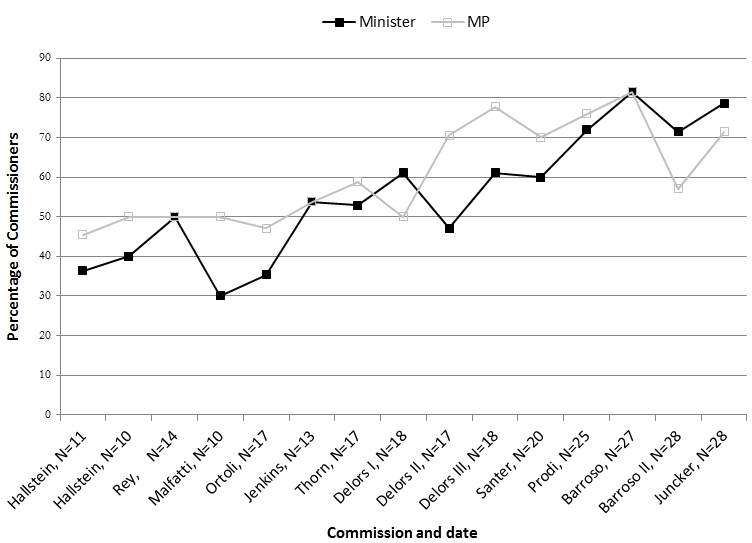

As Chart 2 below shows, since 1985 the overall share of former ministers has increased from 50 to 80 per cent. Since the appointment of Jacques Santer, moreover, all Commission presidents have been former prime ministers. The number of prime ministers among Commissioners, however, has been limited. Only the Barosso-I Commission has had two Commissioners (Siim Kallas from Estonia and Vladimír Špidla from the Czech Republic) who had served as prime ministers before.

Chart 2: Political experience of European Commissioners (1958 – 2014)

Note: In many cases former ministers are also former MPs so both categories overlap.

With a share of former ministers of about 80 per cent, the newly appointed Commissioners fit the pattern from the last 15 years. Yet, the new Commission is rather exceptional with regard to one aspect: the share of former prime ministers among its Commissioners. The European People’s Party chose Juncker as their Spitzenkandidat, who was a prime minister in Luxembourg for almost two decades. However the EU member states also originally nominated four Commissioner candidates who had served as prime minister of their country in recent history: Estonia’s Andrus Ansip, Finland’s Jyrki Katainen, Latvia’s Valdis Dombrovskis, and Slovenia’s Alenka Bratušek.

Of these candidates, the Finnish media speculated that Jyrki Katainen resigned as the country’s prime minister in April 2014 to get a position in the new Commission. The Estonian Prime Minister Andrus Ansip tried a leadership reshuffle with the Commissioner for Transport Siim Kallas in March 2014. Meanwhile, the original (but replaced) Slovenian candidate, Alenka Bratušek, seemingly aimed to secure her nomination when she was still her country’s prime minister. The new Commission thus attracted high profile national politicians, particularly from the smaller EU member states.

The party political profiles of the newly appointed Commissioners do not fundamentally differ from those of the Commissions appointed during the last 15 years. But it reinforces the trend towards a Commission leadership made-up of experienced party politicians with considerable experience in leading large political bureaucracies. The political heavy-weights, the former prime ministers, serve as Vice-Presidents in the new Commission. Juncker assigned greater responsibilities and powers to these positions, by providing them with the political coordination and steering of a number of Commissioners working in functionally and politically related fields. Moreover, the partisan link between nominating governments and Commissioners has never been as tight, as Chart 1 shows.

How the strong political profile of the new Commissioners and Commission President will play out in EU policy-making and politics remains to be seen. Yet, the new Commission’s leadership has the ‘political weight’ to play an active role in shaping the course of the Union in the coming five years. One of the most interesting elements will undoubtedly be how effectively Juncker as Commission President will be able to draw on the (largely symbolic) political capital of being the President of the first ‘parliamentarised’ Commission in the Post-Lisbon era.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: (CC-BY-ND-NC-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1wYfwx7

_________________________________

Arndt Wonka – University of Bremen

Arndt Wonka – University of Bremen

Arndt Wonka is a lecturer at the Bremen International Graduate School of Social Sciences (BIGSSS) and at the University of Bremen. He has published on the European Commission and its role in EU politics, on the institutional and political characteristics of the EU’s administrative system more generally and on interest group and partisan dynamics in EU politics.

Holger Döring – University of Bremen

Holger Döring – University of Bremen

Holger Döring is a lecturer at the Centre for Social Policy Research (ZeS), University of Bremen. He has studied the chain of democratic delegation in the EU by analysing the party composition of EU institutions. His recent work has focused on democratic representation in Western and Central/Eastern Europe.

The success of the Spitzenkandidaten process was also due to another major change in the Lisbon Treaty: now nominations are decided by Qualified Majority Voting. Without that Juncker’s nomination would have been prevented by a British veto. Cameron himself seemed not to grasp that rules had changed when he launched himself into a completely unsuccessful fight against Juncker’s nomination. In the past the UK managed to prevent leading pro-European figures – such as Verhofstadt – from becoming Commission President, in favour of compromise figures such as Barroso. Cameron tried to do the same. But the new decision-making rules made it impossible.

Roberto Castaldi

Associate Professor of Political Theory

eCampus University

Director of researches of the Centre for European and Global Governance

In relation to your point upon the political nature of the process. Would you see this as a benefit to its legitimacy? Surely the aim of the Commission is to provide European thinking ideas forward and to think only about the direction of the EU. This then removing the problems attributed to the competing ideals of member states and political ideologies. Do you not think that the Spitzenkandidaten had meant that this legitimacy can no longer be relied upon.

Thanks