Across Europe there is a wide difference of opinion on the age at which citizens should be given the right to vote. While 18 is still the most common voting age, in 2007 Austria became the first country in the EU to give 16 year olds voting rights for the majority of elections. Recently, the issue has become more prominent in the UK after 16 year olds were allowed to vote in September’s referendum on Scottish independence. As part of LSE’s ‘Expert Voices’ series, Public Policy Group Digital Editor Cheryl Brumley commissioned Sarah Birch, Richard Berry, Philip Cowley, and Andrew Mycock to outline their thoughts on the issue.

[one_half last=”no”][content_boxes layout=”icon-with-title” iconcolor=”” circlecolor=”” circlebordercolor=”” backgroundcolor=””]

[content_box title=”Sarah Birch, Professor of Comparitive Politics, University of Glasgow” icon=”” image=”https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/files/2014/12/sarahbirch.jpg” image_width=”80″ image_height=”108″ link=”” linktarget=”” linktext=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”” animation_speed=””]“If people start voting at the age of 16, there is a greater chance they will vote at their first election and keep on voting.”

[accordian]

[toggle title=”Transcript” open=”no”]

In my view there are significant benefits to reducing the voting age to 16, and this is a measure that should be seriously considered for all UK elections. The main reason I think voting at 16 is a good thing is that we need more young people to vote so that politicians pay greater attention to their interests and their concerns.

As most people know, turnout among young people is far lower than turnout among older groups. This means that politicians of all stripes have little incentive to pay attention to the needs of the younger sector of the population. So we have rising university fees but a triple lock on pensions. We have free bus passes and winter fuel allowances even for well-off pensioners, but the elimination of the Education Maintenance Allowance and cuts to other benefits that are mainly used by young people. Thus, our political system is inequitable.

The most effective way of addressing aged-based political inequality is to get more young people to vote. Short of requiring them to vote by law, the best way of doing this is to reduce the voting age to 16. The resulting influx of young people into the electorate would make politicians of all parties sit up and start paying attention to the concerns of those who will inherit the country for which they are making policy.

In addition, there is evidence from many parts of the world that have lowered the voting age to 16, that 16 and 17 year olds are actually more likely to vote than 18 year olds. This is undoubtedly because many of them live at home with their parents, and go to the polling station as part of a family group.

We also know from a number of studies that voting is habit-forming, and that if people vote at the first election for which they are eligible, they are more likely to continue voting throughout their lives. This means that if people start voting at the age of 16, there is a greater chance they will to vote at their first election and keep on voting.

The combined effect of this would be a gradual improvement in turnout figures and a reduction of the turnout gap between older and younger groups. For all these reasons, I believe it is time to take the idea of voting at 16 seriously. It’s fairer and it would improve turnout.

[/toggle]

[/accordian]

[/content_box] [/one_half]

[one_half last=”yes”][content_boxes layout=”icon-with-title” iconcolor=”” circlecolor=”” circlebordercolor=”” backgroundcolor=””]

[content_box title=”Richard Berry, Research Associate, Democratic Audit UK and LSE Public Policy Group” icon=”” image=”https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/files/2013/11/RichardBerry.jpeg” image_width=”80″ image_height=”108″ link=”” linktarget=”” linktext=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”” animation_speed=””]

“A 16 year old isn’t putting themselves or others in physical danger or making a life-changing decision by voting”

[accordian]

[toggle title=”Transcript” open=”no”]

In a modern democracy, the right to vote is meant to be a universal right enjoyed by all citizens. But it has taken a long time for that principle to become established. British democracy began with barriers to voting based on age, gender and property ownership. Gradually we’ve extended the franchise to include these groups that were previously excluded.

This process hasn’t finished yet. We’re still dealing with the question of who should and shouldn’t be allowed to participate in elections. For instance, in 2006, the Electoral Administration Act clarified that people with learning disabilities are entitled to vote, the government currently has proposals to overturn the ban on voting for UK citizens who have lived abroad for more than 15 years, and the European Court of Human Rights has ruled that convicted prisoners must be given voting rights.

The debate on votes at 16 is part of this long tradition. There is a common assumption that 18 is the recognised age of adulthood. But if we consider what age people acquire different rights and responsibilities, there is clearly no agreed point at which we become adults. The right to drink, marry, have sex, drive or vote are all gained at different ages, usually with different qualifications in place.

For instance, you can have sex at 16, but if you want to marry your partner you need parental permission. The right to drive kicks in at 17, but it is only available to those people who have proven their competence by passing a driving test. We calibrate these rights according to the risks involved in each activity. The higher the risk, the older the age threshold, and the more qualifications are placed on the right.

Voting is not a risky activity. Not in the UK, anyway. A 16 year old isn’t putting themselves or others in physical danger, or making a life-changing decision, by putting a cross on a ballot paper. And while there’s always the risk for society that incompetent candidates are elected, or unworkable policy pledges are made, we’d need to have a very low opinion of the maturity of 16 and 17 year olds to think they are going to increase that danger any higher than it already is.

There are 1.5 million 16 and 17 year olds in the UK. It has taken a very long time for this group to start demanding the vote. But educational standards are higher than ever. Perhaps thanks to the internet, young people’s awareness of the world around them is higher than ever. Anyone who has spent any time whatsoever engaging young people in political discussion will know that they are as capable as anyone to contribute their views in a mature, considered way.

While I’m sure there are many exceptions to this rule, we can just as easily find exceptions among older age groups too. Lowering the voting age is not a panacea for the problem of youth disengagement from politics. But with growing demand for this change, not lowering it would send out a powerful message that the political class is content with the way things are.

[/toggle]

[/accordian][/content_box] [/one_half]

[one_half last=”no”][content_boxes layout=”icon-with-title” iconcolor=”” circlecolor=”” circlebordercolor=”” backgroundcolor=””]

[content_box title=”Philip Cowley, Professor at University of Nottingham” icon=”” image=”https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/files/2014/12/philipcowley.jpg” image_width=”80″ image_height=”108″ link=”” linktarget=”” linktext=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”” animation_speed=””]

“The arguments themselves for giving the vote to 16 year-olds, I’m afraid, don’t stack up.”

[accordian]

[toggle title=”Transcript” open=”no”]

I think I understand why people are thinking about giving the vote to 16 year olds. There are certainly a lot of 16 year olds who would execute the vote wisely and they would do so just as well as many older voters. And I particularly understand that when we have a problem with democratic trust and participation in politics why people are considering doing this. The problem is that it falls into the category of solutions when people say, “We must do something. This is something. Let’s do it.”

The arguments themselves for giving the vote to 16 year-olds, I’m afraid, don’t stack up. I’d distinguish two particular problems with it: the first is that most of the arguments we are given for why we should lower the voting age aren’t actually true when you look at them in detail. To take some regularly cited examples: You’re told that people can join the army at 16; they can get married at 16. Well, in England and Wales they can get married but they still need parental permission. They can join the army at 16 but again, they need permission to do so. And in fact, they are not allowed to see frontline service until the age of 18. If you look at the various ages at which we give rights and responsibilities in Britain, far more of them are 18 than 16.

My other problem with it is the way that people more broadly view this. There is widespread public support for keeping the voting age at 18. The Hansard Society a few years ago did a survey where they asked people which bits of the constitution they understood and which bits of the constitution people liked. There was only one bit of the constitution where people both understood and liked it and that was the voting age being 18. Overwhelmingly, majorities in opinion polls say they want to keep the voting age at 18 so I find it really difficult when constructing a mechanism to reengage the public with democracy, that we would do something so many of them don’t want.

[/toggle]

[/accordian][/content_box] [/one_half]

[one_half last=”yes”][content_boxes layout=”icon-with-title” iconcolor=”” circlecolor=”” circlebordercolor=”” backgroundcolor=””]

[content_box title=”Dr Andrew Mycock, Reader in Politics, University of Huddersfield” icon=”” image=”https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/files/2014/12/andrewmycock.jpg” image_width=”80″ image_height=”108″ link=”” linktarget=”” linktext=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”” animation_speed=””]

“Lowering the voting age could prove a dangerous, rather than radical, step.”

[accordian]

[toggle title=”Transcript” open=”no”]

I sat on the youth citizenship commission between 2008-2009, which last looked at the case for lowering the voting age. We came to the conclusion that the conditions weren’t right for lowering the voting age and I’m of the opinion that little has changed since that conclusion. Allowing young people to vote at 16 will not fix the problem of youth disengagement with politics and, indeed, there is a question here about the impact of the Scottish independence referendum.

I think that one of the main problems is that the potential for votes at 16 to make British political culture more youth-centric and youth-sensitive is also debatable. It may well redress some demographic imbalances in the electorate, but it is unlikely to have a dramatic effect on the attitudes or political behaviour of most politicians or political parties towards younger voters. Political parties remain instinctively focused on older voters and maybe that’s because they instinctively understand and represent older voters’ interests.

Young people are instead annexed into youth wings within political parties, where their policy interests are often compartmentalised or banished to the periphery. No other age group is treated that way. There is a need for political parties to change the way in which they approach young people’s politics before the voting age is lowered.

Another issue which is raised is the idea that voting age should match the age in which young citizens get other rights, particularly as they can join the army, get married or pay tax at a young age. But the problem is that these rights are not universally realised at the age of 16 and indeed, the age of responsibility is increasingly being delayed. Young people’s rights are being pushed upwards and it is highly likely in the next general election that young people’s access to social rights such as housing benefits is going to be restricted further.

Indeed there is an inverse problem here. We could start to see young people being able to vote before they can do other things. The problem is that it could introduce a form of two-tier citizenship, where young people actually feel more excluded if they’re allowed to realise a number of social and economic rights.

Votes at 16 may well arrest the decline in electoral turnouts in the short term, but will not fix the problem of youth disengagement with politics. Political parties need to do more to involve young people in the whole political process or they could actually encourage disconnection at an earlier age. Lowering the voting age of enfranchisement to 16 without discussing the wide-range of implications could prove a dangerous, rather than radical step.

[/toggle]

[/accordian][/content_box] [/one_half]

[separator top=”40″ style=”none”][title size=”2″]Votes at 16 infographics[/title]

[fusion_tabs layout=”horizontal” backgroundcolor=”” inactivecolor=””]

[fusion_tab title=”Voting as a social norm”]

“Voting in general elections is the norm around here”

Research suggests 16 and 17 year olds, who predominantly live at home with their parents, have a stronger sense of ‘voting as a norm’ than older age categories.

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”Parental influence on voting”]

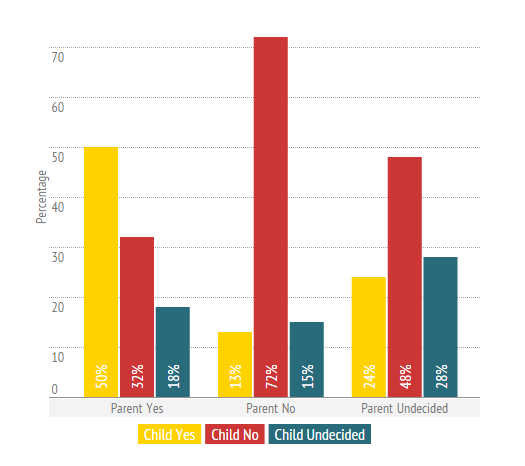

Voting intention in Scottish Independence referendum of 14-17 year olds compared to parent’s intention.

Do younger voters merely follow the political preferences of their parents?

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”Interest in politics”]

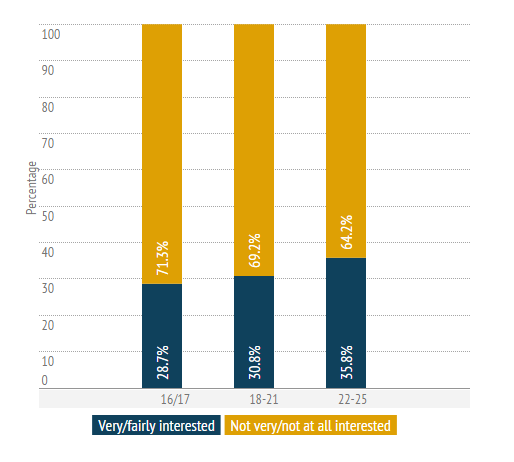

How interested are young people in politics?

Despite not being allowed to vote, 16 and 17 year olds have a very similar level of interest in politics as 18 to 21 year olds.

[/fusion_tab]

[/fusion_tabs]

_________________________________

Note: This post was originally published on the Democratic Audit blog and represents the views of the interviewees and not those of EUROPP or the LSE. Data in graphs all sourced from ScotCen Social Research. Featured image credit: Kamyar Adl (CC-BY-SA-3.0)