From Podemos to the Front National and the Five Star Movement, mainstream parties in Europe are increasingly being challenged by ‘outsider’ parties on the radical-left and far-right in several European countries. But with the proliferation of new parties how is electoral support affected by strategic voting? Annika Fredén writes on the differing fortunes of small parties in Sweden and Germany in recent elections. She argues that the extent to which smaller parties benefit from strategic voting is highly dependent on signalling prior to polling day, and that parties in tight contests such as the 2015 general election in the UK could therefore benefit from pre-election agreements.

From Podemos to the Front National and the Five Star Movement, mainstream parties in Europe are increasingly being challenged by ‘outsider’ parties on the radical-left and far-right in several European countries. But with the proliferation of new parties how is electoral support affected by strategic voting? Annika Fredén writes on the differing fortunes of small parties in Sweden and Germany in recent elections. She argues that the extent to which smaller parties benefit from strategic voting is highly dependent on signalling prior to polling day, and that parties in tight contests such as the 2015 general election in the UK could therefore benefit from pre-election agreements.

Just before the 2010 Swedish General election the then Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt called on voters to elect a centre-right “Alliance” which could deliver a stable government. When voters finally went to the polls, a large part of his own Moderate Party’s supporters chose to vote for the smaller coalition member, the Christian Democrats.

In the most recent general election in Germany, on the other hand, the two right-wing government parties (the centre-right CDU/CSU and the liberal FDP) ran separate campaigns, with the FDP unexpectedly falling below the electoral threshold. In Sweden in 2010 there were two clear pre-electoral coalitions, whereas in Germany in 2013 the coalition signals were weaker, but how do these contextual factors influence the decision to vote for a small party? In this post I take a closer look at the relationship between coalition signals and strategic voting for small parties.

Different types of strategic voting

Strategic voting is usually defined as voters choosing to back an alternative party to the one they prefer so as to affect the overall outcome of an election. It is most straight-forward in first-past-the-post systems, such as in the UK, where voters who prefer a small party may abandon it for some other party that is more likely to gain a seat. In proportional representation systems (PR) a larger number of parties are represented and governments tend to consist of a coalition of parties. Even under PR, however, voters may cast strategic votes for large parties, since these have a greater chance of gaining influence and leading a government.

There are also incentives to cast strategic votes for small members of a potential coalition. In most PR systems there is an electoral threshold of the minimum share of votes a party must receive to get elected, making votes for smaller parties potentially more influential on the distribution of seats than voting for a larger party. The presence of the small party in parliament may even make the difference between winning and losing the election as a coalition.

The signals that parties send out about the party or parties they wish to cooperate with should affect this kind of strategic voting, which is sometimes referred to as ‘threshold insurance voting’. If some parties explicitly announce that they intend to form a coalition if they would win, supporters of the larger parties should in theory be more likely to defect to a smaller partner.

Evidence from Sweden

Recent research illustrates that this form of ‘insurance voting’ has taken place in Germany, Austria, and Sweden, among other European countries. The 2010 national election in Sweden serves as a case in point, in which the pre-electoral coalitions were very clear: the parties to the left competed with the incumbent four-party centre-right coalition.

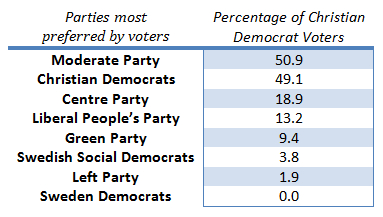

Before the election, polls showed that the Christian Democrats, who classify as a social-conservative party and were a member of Reinfeldt’s centre-right Alliance, were the party most at risk of falling below the threshold. Analyses based on the Swedish national election study show that among those who voted for the Christian Democrats, a majority actually viewed the Moderates as their preferred party, as shown in the Table below.

Table: Party preference among Christian Democrat voters in 2010 Swedish general election

Note: The parties preferred by voters are in accordance with voter responses to an 11 point sympathy scale in the 2010 Swedish National Election Study. The party ‘most preferred’ is the party (or parties) which received the highest score by a voter. Several respondents gave more than one party the highest score on this scale so the percentages in the right hand column overlap.

As the Table illustrates, in this election many supporters of the biggest right-wing party (the Moderates) chose to cast a vote for a smaller coalition member. Controlling for other factors that affect choice, such as party identification and position on a political left-right scale in a multivariate model, threshold insurance motivations had a significant impact on votes for the Christian Democrats.

In contrast, in the 2013 German federal election, the incumbent centre-right coalition (CDU/CSU and FDP) ran separate campaigns. Whereas the FDP in previous elections had received strategic votes from CDU/CSU-supporters, this time the FDP fell below the 5 per cent threshold. Alternatively, in the 2014 Swedish general election, there were two small parties at risk of not reaching the four per cent electoral threshold: the Christian Democrats and the outsider Feminist Initiative on the left side. In this election, the coalition signals from the leading left party, the Swedish Social Democrats, were ambiguous, and Feminist Initiative fell short of the threshold, whereas the Christian Democrats were elected again.

While it is difficult to pinpoint these effects in different countries, there is ample evidence that coalition signals and polls do matter for strategic voting for small parties under PR systems. Coalition negotiations before an election provide parties with credibility and a perceived increase in influence. With strategic voting becoming ever more important in countries like the UK, with a greater number of options for voters than ever before, coalition considerations are also becoming more relevant for first-past-the post elections.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article originally appeared at our sister site, Democratic Audit, and gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Mando Gomez (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1aoCoP8

_________________________________

Annika Fredén – Lund University

Annika Fredén – Lund University

Annika Fredén is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Lund University in Sweden, specializing in strategic voting behaviour and experimental methods.

Yet another reason for preferring the Single Transferable Vote to party-list proportional systems. STV effectively has a threshold, but does it in a way that avoids wasted votes. Here, those whose top two preferences were the Christian Democrats and Moderates could have safely put their real preference first, without worrying about threshold effects.

I would be interested to learn wheher Sweden – or indeed any non-English speaking democracy – has ever considered STV. Is their something cultiural in preferring party-based to individual-based electoral systems?