Support for individual political parties has changed substantially since the start of the crisis in Greece, with Syriza emerging as the largest party in the 2015 elections, while other parties, such as Pasok, have lost most of their support. But beyond the electoral success of parties, what effect has the crisis had on wider political culture within Greece? Gerasimos Karoulas writes that the crisis has also had a profound effect on the types of individuals holding political power. Time will tell, however, whether this change in the composition of the parliament and government will also lead to long-term policy changes.

Support for individual political parties has changed substantially since the start of the crisis in Greece, with Syriza emerging as the largest party in the 2015 elections, while other parties, such as Pasok, have lost most of their support. But beyond the electoral success of parties, what effect has the crisis had on wider political culture within Greece? Gerasimos Karoulas writes that the crisis has also had a profound effect on the types of individuals holding political power. Time will tell, however, whether this change in the composition of the parliament and government will also lead to long-term policy changes.

The results of the Greek elections in January underlined the transformation in Greek political culture that has taken place during the crisis. Alongside Syriza emerging as the leading political force in the country – and the first radical left party to gain power – there was also a high turnover of new MPs, with 40 per cent (118) of the new members of the Greek parliament being elected for the first time. The turnover of politicians is even more pronounced if we consider that almost half of the MPs elected in the Greek elections in May 2012 were also newcomers to parliament.

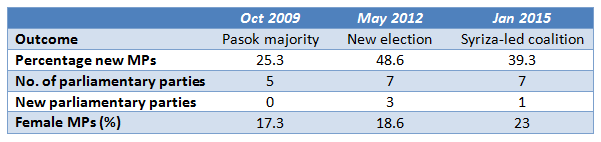

In the 2015 elections, Syriza accounted for the bulk of these new members (87), with other parties such as the recently formed To Potami (The River) also contributing, albeit to a lesser extent. Moreover, the number of new female MPs being elected also increased, with 69 (23 per cent) of representatives being women. This was mostly down to Syriza, who accounted for 44 of the female MPs (30 per cent of its total representatives). In some respects, however, the elections were less of a break with the past: the non-political professions of MPs were largely similar to those in previous parliaments, with lawyers, academics, journalists, economists, doctors, and mechanics having the highest levels of representation. The Table below puts these trends in context for the 2009 Greek parliamentary election, the May 2012 election, and the 2015 election.

Table: Comparison of three Greek elections before and during the crisis

Note: The new election called after the election in May 2012 was held in June 2012.

The nature of the government which emerged in January also illustrates some of the changes which have occurred in the Greek party system. There are 41 members currently serving as ministers, alternate ministers, or deputy ministers, with power split between Syriza and their coalition partner, the Independent Greeks. As a first point, it is worth noting that only two of these figures had taken substantial roles in previous governments: the leader of the Independent Greeks, Panos Kammenos, who was previously a member of New Democracy; and Yannis Dragasakis, who is currently Deputy Prime Minister.

Similarly only 12 of the 41 members have noteworthy parliamentary experience, given the rest were either elected for the first time in 2012 or during the 2015 elections. Moreover, 14 of the members joined the government as non-parliamentary representatives – an extremely high number by traditional standards. The only recent government that had a similar composition was the government under Xenophon Zolotas in 1989, which also emerged as a result of a crisis in the Greek political system. In the current government, the situation is justified by the fact most of the non-parliamentary representatives have some form of technical expertise. In previous governments appointments were more strictly geared toward intraparty balances or individual popularity/power of members.

In terms of the demographic profile of the cabinet, it could be argued that in most cases it is similar to the trends visible in previous years, including the limited participation of women and the powerful role afforded to specific occupations such as academics. Despite 44 female Syriza MPs being elected, only 6 women made it into the government in any capacity, including two members of the Independent Greeks. Academics account for the largest occupation group in the government with 14 members, followed by engineers (5), economists (5), civil servants (4) and lawyers (4). Indeed the government overall exhibits a high level of education, with 15 members possessing a doctorate, a further 9 member holding a Master’s degree, and 17 having studied abroad.

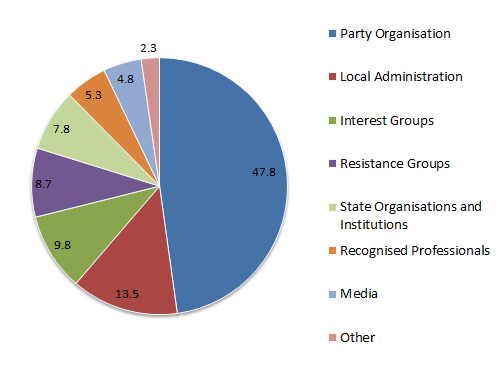

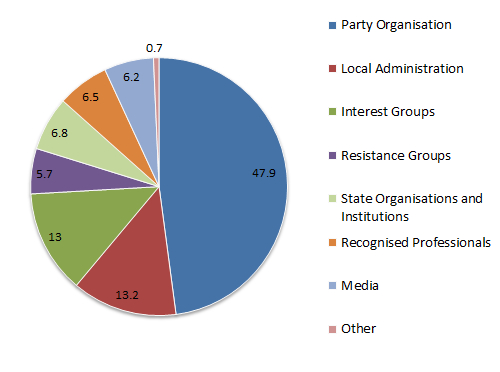

However, and in contrast to the young age of Alexis Tsipras and some of his close associates (i.e. Nikos Pappas and Gabriel Sakellaridis) who were appointed to the cabinet, the mean age of government members is very high, at about 60 years old. This is to a large extent connected to the issue of the recruitment channels for politicians, which have been influenced by the crisis conditions. As shown in the chart below, the recruitment of politicians from party organisations has fallen to some degree, with figures being drawn more frequently from other sources such as the media and local administration.

Chart: Change in recruitment channels for Greek politicians (MPS, MEPs, non-parliamentarian members of the government)

[fusion_tabs layout=”horizontal” backgroundcolor=”” inactivecolor=””]

[fusion_tab title=”Pre-1990″]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”1991-2000″]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”2001-2010″]

[/fusion_tab]

[/fusion_tabs]

Note: Each chart shows the percentage of Greek politicians who emerged in the indicated period (MPs, MEPs and non-parliamentarian members of the government) from a given sector.

However, the composition of the government has derived from completely different recruitment channels. As might be expected, party officials make up a larger share of those in government, but there are also growing numbers of individuals in government who have been recruited on the basis of technical expertise (academics), their participation in civil society, or due to previous involvement in social movements. This is particularly the case due to the collapse of Pasok and New Democracy (the two largest parties in Greece prior to the crisis) who had both imposed strong partisanship in some of these areas. On the other hand, local administration and state bureaucracy do not appear to act as strong recruitment bases for figures in the government.

One final observation which is worth making is the fact that family connections, which have had a strong role in shaping Greek political culture, are no longer as evident in the makeup of the current government. Only in one case is there a family connection between two members: Thodoris Dritsas and Tasia Christodoulopoulou, who are married. Of course even this case is not the traditional model of family influence in Greek politics (where sons, grandsons and nephews have periodically been promoted into positions of influence) and both members have a long history in the intraparty organs of Syriza.

Ultimately there is little question that Greece has undergone a substantial transformation in its political culture since the crisis began. What remains to be seen is whether this transformation in the composition of parliament and government is matched by a similar change of course in policy.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Dimitris Agelakis (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1FG8WBj

_________________________________

Gerasimos Karoulas – National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

Gerasimos Karoulas – National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

Gerasimos Karoulas is a PhD Candidate at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.