Croatia’s government, led by Zoran Milanović, is now into its last year in power before elections scheduled for the start of 2016. Will Bartlett writes on the government’s economic record. He argues that Milanović’s decision to continue with the previous government’s policy of fiscal consolidation has had dismal consequences for the country’s economy. The only hope is that if growth resumes in the EU it will pick up the Croatian economy along with it.

Croatia’s government, led by Zoran Milanović, is now into its last year in power before elections scheduled for the start of 2016. Will Bartlett writes on the government’s economic record. He argues that Milanović’s decision to continue with the previous government’s policy of fiscal consolidation has had dismal consequences for the country’s economy. The only hope is that if growth resumes in the EU it will pick up the Croatian economy along with it.

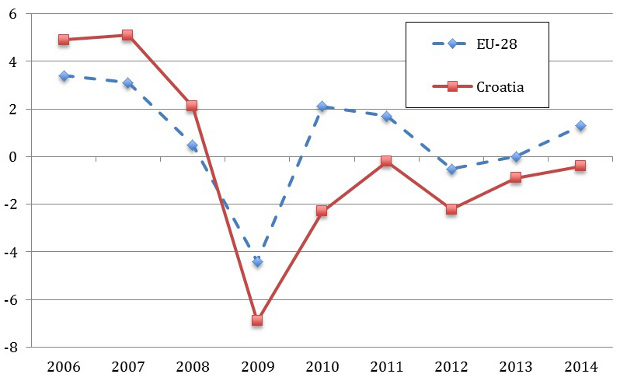

The Croatian government led by Zoran Milanović has been in power for over three years. During this time, the economy has been subject to a continuing recession, having experienced negative GDP growth over the entire period, as shown in Chart 1 below.

Chart 1: Real annual GDP growth, Croatia and EU-28 (2006-14)

Source: Eurostat online data

The downturn has had serious social consequences. The unemployment rate has almost doubled from the low of 9 per cent in 2008 to a new peak of 17 per cent in 2013. A similar pattern has affected youth unemployment, which had increased to around 50 per cent by 2014. In the words of the European Commission, this has placed a “strain on the social fabric”, while low employment rates are damaging growth prospects. This poor economic performance indicates deep structural problems and difficulties in adjusting the economy in the wake of the initial recession, and raises questions about the appropriateness of economic policy since then.

Policy response to the crisis

Since it came to power in December 2011, The Milanović government has continued on the track of fiscal consolidation announced by the previous government. The aim of the government has been to shift towards an investment led model of growth, while simultaneously reducing the tax wedge (taxes and social contributions on labour) to encourage employers to hire more workers. Additional reforms in the labour market and to social contributions were to be introduced to provide additional incentives to the supply side of the labour market.

In its first budget in 2012, the new government announced cuts to the wage bill, to subsidies, and to health spending. VAT was increased by 2 per cent combined with a 2 per cent reduction in social health contributions designed to ease the burden of social contributions on wages and boost employment. A personal income tax allowance was introduced for low earners, while a 12 per cent tax was introduced on profits and dividends, measures designed to change the balance of taxation away from labour and towards capital.

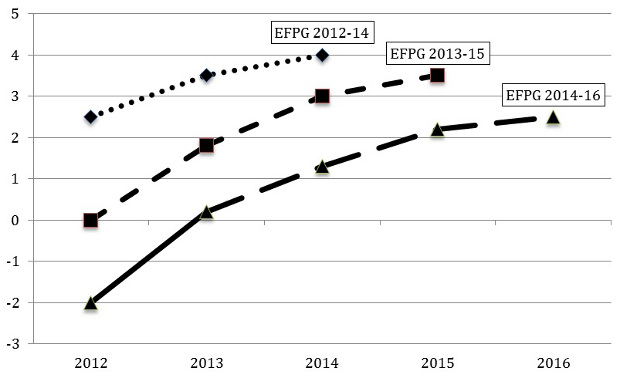

These measures represented a continuation of economic policy of the previous HDZ government combined with some modest redistribution elements. However, the initial aim to boost investment was overshadowed by the decision to continue with the previous government’s policy of fiscal consolidation, which, by reducing public expenditure at a steady 1 per cent per year, removed purchasing power from the economy and undermined all other attempts at stimulating growth. The inevitable result has been a continued deterioration of the economy, and all projections for recovery that were predicted by the government’s macroeconomic forecasts have been continuously downgraded – as shown in Chart 2 below.

Chart 2: Government forecasts of growth have been constantly downgraded over time

Note: Dashed lines indicate forecasts. Source: Economic and Fiscal Policy Guidelines, Ministry of Finance, Zagreb; various years as indicated.

Policy measures within the EU – the excessive deficit procedure

Soon after Croatia joined the EU in July 2013, the Milanović government had to cede effective control over many aspects of economic policy to the European Commission. The EU had adopted a system of “new economic governance” in 2010 in response to the Eurozone crisis. As a member state, Croatia became immediately involved in the annual “European Semester” that begins in November with the publication of an Alert Mechanism Report (AMR) for all EU member states.

The AMR of November 2013 stated that Croatia had a “severe macroeconomic imbalance” that required further investigation through the process of an In-Depth Review (IDR). Even before the results of the IDR were announced, Croatia was placed in the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDF) in January 2014. From that point on, the most important instruments of economic policy were effectively taken away from the independent responsibility of the Croatian Government and handed over to the European Commission.

The IDR, published on 5 March 2014, identified a range of serious problems including large external liabilities, declining export performance, highly leveraged firms and fast growing government debt. It also revealed that state owned companies had not been restructured, were highly indebted and were only weakly profitable, that Croatia has the lowest employment rates in the EU, and that the business environment ranks below the average of all the EU’s post-communist states.

On 24 April, Croatia submitted its 2014 National Reform Programme and Convergence Programme to the European Commission. The latter outlined the budgetary strategy to correct the excessive deficit by 2016, reducing the deficit from 4.9 per cent of GDP in 2013 to 3 per cent of GDP in 2016, to meet the EDF target. The Commission responded in June 2014 with a set of recommendations that heavily criticised the Convergence Programme for basing the forecasts on overly optimistic projections of economic growth in the forthcoming years. Overall, it assessed that additional efforts would be needed in order to comply with the recommendations under the EDP to correct the excessive deficit by 2016.

In November 2014, the Commission issued its fourth annual Alert Mechanism Report. The report’s conclusions on Croatia’s economy were that macroeconomic imbalances remained a “serious concern”. The AMR found that the large negative net international investment position had improved slightly because the current account had returned to a surplus due to falling domestic demand and investment.

However, low investment was undermining economic recovery and Croatia was steadily losing its share of the global market. It also assessed that unit labour costs and the real effective exchange rate were starting to rise again, putting any gains made in improving competitiveness at risk. Furthermore, the contracting economy and the high budget deficits had put the public debt to GDP ratio on to a rapidly rising trend.

Labour market policy

One of the key concerns of the European Commission has been the poor performance of the labour market, especially for the youth and for older workers. An increasing number of young people are neither in education, employment nor training, while the proportion of people at risk of poverty and social exclusion has increased to levels significantly above the EU average. Policy makers have therefore stressed the importance of structural reforms designed to make the supply side of the economy more flexible in the hope of stimulating economic growth.

New laws on Social Welfare and on Pension Insurance adopted in January 2014 have restricted social benefits, raised the pension age, encouraged pensioners to take up part time employment, increased penalties for early retirement, tightened criteria for the receipt of disability benefits, extended the maximum period of fixed term employment contracts, and made it easier for employers to dismiss probationary workers. The aim of making the labour market more flexible has been to enable a positive employment response in case of an economic upturn.

Unfortunately a flexible labour market can also have the opposite effect during an economic slowdown, magnifying the extent of job losses. Supply-side policies are unlikely to have a positive effect in conditions where aggregate demand is insufficient to bring the economy to a position where capacity constraints are beginning to bite. From that point onwards a more flexible labour market and a more flexible economy can have the effect of releasing the supply constraints that might otherwise hold back growth.

However, after five years of recession, it can be stated with some certainty that the Croatian economy is far away from its full capacity constraint. The danger of continuing with such a policy will be that the capacity constraint actually shrinks to meet the lower level of aggregate demand, and that the lower level of output and productivity engendered by the long recession may become a permanent feature of the Croatian economy.

Attracting foreign direct investment

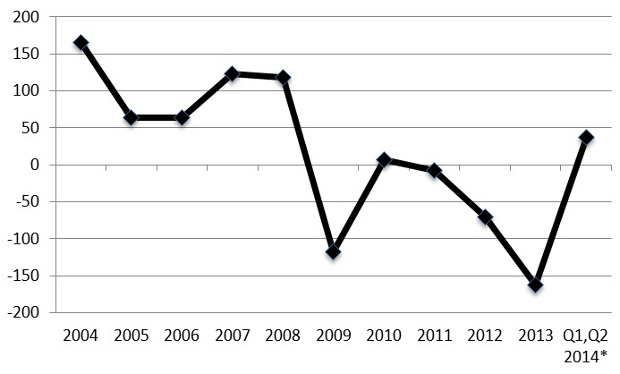

During the pre-crisis boom period, new foreign direct investment (FDI) to Croatia reached a high point of US$6 billion in 2008. Since then, as in most other peripheral European economies, the inflow of FDI has come to an end. The supply of foreign capital has diminished as a consequence of the economic crisis and investors are more concerned to reduce risk by investing in safer options such as cash and the government bonds of safe countries.

Chart 3: Foreign direct investment (US$ million)

Source: UNCTAD online data

Along with the reduction of the inflow of foreign investment, foreign investors already in the country have become less willing to reinvest their profits in order to expand capacity and increase productivity. As can be seen from Chart 4, profit reinvestment by foreign investors turned negative after the onset of the crisis in 2009, indicating that substantial sums were actually leaving the country rather than being reinvested in the economy. Only recently has the situation recovered in the first two quarters of 2014, perhaps indicating the beginnings of a return of confidence, and a positive effect from Croatia’s EU membership.

Chart 4: Foreign investors’ reinvestment of profits

Source: Croatian National Bank online data

In order to promote foreign investment, the government introduced a new foreign investment Law in 2012. The new law reduced the minimum initial investment amount and created special conditions for micro-entrepreneurs; introduced a new investment category for investments in high value- added activities; increased the subsidies for job creation; provided special treatment for investment projects that created more than one hundred new jobs; and changed the method of calculating the amount of the initial investment.

Despite the enactment of this law, foreign investment continued to plunge in 2013. There were some signs of a recovery in the first half of 2014, but this has probably been due more to Croatia’s entry into the EU than to the provision of special financial incentives and privileged market conditions for foreign investors.

Conclusions

Overall, the Milanović government has had a rather dismal record in relation to the management of the economy, which has continued to languish in recession for a far longer time than almost any other European country. By 2014, the economy had suffered from five years of recession, unemployment had been continually increasing, and few economic indicators had shown positive news.

The principal reason for the recession has been the decision to impose pro-cyclical fiscal consolidation on an economy hard hit by the global crisis. While the onset of the economic crisis can plausibly be placed on outside factors, principally the shock induced by the global financial crisis and subsequently to the spill-over effects of the Eurozone crisis, the inability of the Croatian economy to recover from these shocks indicates serious problems of a deep-seated structural nature and that government policies have not yet been sufficiently effective.

When the Milanović government came to power in 2011, it held a fairly progressive policy aim of rekindling economic growth and creating a more equal society. This was to be achieved through an investment programme to raise capacity and improve productivity, and some redistribution to the lower wage earners that would boost consumption and aggregate demand.

Unfortunately, in the priority given to fiscal consolidation few of these plans came to fruition. While these aims remain a valid policy option for emerging from the recession, they are unlikely to be fulfilled within the scope of the EU’s Excessive Deficit Procedure. One must hope that growth resumes in the EU, and that this will lift the Croatian economy along with it, and also that the capacity of the economy to respond to such a future opportunity will not have been too greatly diminished by the policies adopted over the last five years by successive governments.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: A version of this article originally appeared at our partner site, LSEE – Research on South Eastern Europe. The article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Daniel Skinner (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1G0WPgF

_________________________________

Will Bartlett – LSE

Will Bartlett – LSE

Dr Will Bartlett is Senior Research Fellow in the Political Economy of South East Europe at LSE Research on SEE, London School of Economics. In 2006-08 he was President of the European Association for Comparative Economics. He coordinates the LSEE Research Network on Social Cohesion in South Eastern Europe.