How have minority communities in France been affected by the Paris terrorist attacks in January? Joseph Downing, Jennifer Jackson-Preece and Maria Werdine-Norris write that the response to the attacks has highlighted a long-term trend in French politics: the focus on issues of security and the perceived threat posed to the French nation by ‘outsiders’.

How have minority communities in France been affected by the Paris terrorist attacks in January? Joseph Downing, Jennifer Jackson-Preece and Maria Werdine-Norris write that the response to the attacks has highlighted a long-term trend in French politics: the focus on issues of security and the perceived threat posed to the French nation by ‘outsiders’.

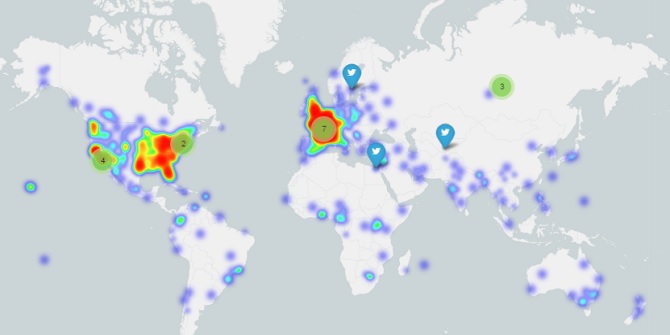

The Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris sent a shockwave through Europe. Images of masked gunmen rampaging through the streets of Paris and the resulting mass vigils in Place de la Republique have become iconic images of the threats to freedom of speech and security in Europe. They have also come to represent a public backlash against the use of violence as a political tool to shape, control and dictate agendas in democracies. The rise of the Je suis Charlieslogan on social media demonstrated the increased use of symbolic and narrative means of expressing the nation’s sentiments in an era long dominated by mass media. It also underlined the maturity of the ‘politics of the deed’ into an endeavour with a global audience.

The response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks represent something important about a longer term trend in French politics that is becoming ever more prevalent. This is the situation of the nation, its values, institutions and existence as an issue of security, faced with an ‘existential threat’ from ‘outsiders’. Viewing this from the perspective of the Copenhagen school of ‘securitisation’ this is a worrying development. This is because the movement of an issue from the realm of normal politics into the realm of emergency, security politics, puts in place a dynamic that can justify the use of extra-judicial measures to stem such threats.

In France this is a particular concern because of the construction of exactly who these outsiders are that pose existential threats to the nation. This narrative has overwhelmingly focused on those of minority origin from France’s ex-colonies in North and West Africa. The construction of these minority communities as threats to the nation has far longer roots than those found in recent political events. Since the mid-1980s these communities have continually been labeled as ‘urban outcasts’, engaged in a ‘French intifada’ with the exclusionary state and national culture, situated in the rundown ‘suburbs of the Republic’ of large French cities.

These overlapping ‘intersecting’ notions of threat demonstrate something very important about the process through which groups become constructed as threats to the nation. The notion of ‘urban outcasts’, epitomised by images of hooded young males of minority extraction fighting with the police (most notably in 2005) demonstrated an important class element to the construction of threat. This bears striking commonalities with discussions of the underclass in 1980s Chicago, with the addition that in the French case, because of direct battles with the police, these groups were constructed as threats to the nation itself. The most striking expression came in the declaring of a national state of emergency by the French state in 2005. This was the result of consecutive nights of rioting across France after the death of two youths fleeing the police.

However, since 2005, the construction of threat has increasingly taken a worryingly religious turn. This turn specifically identifies Muslims as a threat to the French nation. It has deep historical roots, with the focus on a form of aggressive secularism (Laïcité) as a key identifying factor of France’s Republican model of governance. Here, religion is not simply removed from politics, but is not recognised by the central state, which is forbidden from funding any religious institution or even collecting statistics on religious observance in France.

However, this stance on secularism has been taken up and used by those seeking to marginalise particular minorities in France. The far-right Front National has long used the rhetoric of religious threat when discussing France’s Muslim minority, the largest in Europe. Here, the party compares the presence of Muslim communities in France to the threat to French independence posed by the Nazi occupation.The fact that scholars have discussed the threat to the nation in terms of a pseudo-religious “French Intifada” shows the seductive nature of simplistic, essentialist and “orientalist” understandings of contemporary French politics and security.

However, out of the estimated 5 million individuals of Muslim origin in France, those engaged in a violent confrontation with the French state are tiny. Indeed, as the number of violent attacks against Muslims and Islamic institutions continues to increase in France, it is those of Muslim origin who are increasingly likely to be the victims of violence and discrimination. This is not an isolated trend in France, however, as there is also a worrying trend of increasing violence directed against the country’s Jewish population.

This raises the important question of what can be done to reduce this construction of minorities as a ‘threat’ to the nation. Social media gives some important pointers. Another slogan, Je suis Ahmed, appeared in memory of the police officer of North African Muslim origin, Ahmed Merabet, who was killed in the attack. This demonstrated that there are a significant number of minorities in the French armed security services who work not to threaten the nation, but rather to protect it. It is also interesting to note that during the Tolouse attacks of 2012, three of those killed were French soldiers of North African origin. All of this indicates that the central concern of nationalism – that is, the drawing of boundaries between insiders and outsiders – remains at the forefront of French politics, society and national security.

The 25th Annual ASEN conference “Nationalism; Diversity and Security” takes place at LSE from 21-23 April 2015 and will include a workshop by Dr Jennifer Jackson-Preece on Securitising the Nation in Europe after Charlie Hebdo.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1D1qiCb

_________________________________

Joseph Downing – LSE

Joseph Downing – LSE

Dr Joseph Downing is a guest teacher in the LSE’s European Institute and a Fellow for LSE100. His research to date has focused on nationalism, integration and minorities in France. He is also co-chair of the 2015 ASEN conference “Nationalism; Diversity and Security”.

Jennifer Jackson-Preece – LSE

Jennifer Jackson-Preece – LSE

Dr Jennifer Jackson-Preece is Associate Professor of Nationalism in the LSE’s European Institute and has worked extensively on minority rights in Europe, including chairing the European Centre for Minority Issues Advisory Council.

Maria Werdine-Norris – LSE

Maria Werdine-Norris is a GTA in the LSE’s Government Department where she teaches a course on Nationalism. Her PhD focuses on counter-terrorism in the UK. She is also co-chair of the 2015 ASEN conference “Nationalism; Diversity and Security”.