The island of Lampedusa has become the focal point of attempts to address irregular migration in the Mediterranean, but how does the EU’s border system at Lampedusa actually function? Giacomo Orsini writes on the nature of the system, noting that it represents a complex combination of surveillance and detention measures. He argues however that the attention focused on Lampedusa itself is disproportionate, with the majority of undocumented migration into the EU taking place via other routes.

The island of Lampedusa has become the focal point of attempts to address irregular migration in the Mediterranean, but how does the EU’s border system at Lampedusa actually function? Giacomo Orsini writes on the nature of the system, noting that it represents a complex combination of surveillance and detention measures. He argues however that the attention focused on Lampedusa itself is disproportionate, with the majority of undocumented migration into the EU taking place via other routes.

Lampedusa constitutes ‘the quintessential embodiment of the Euro-African migration and border regime’. Yet what precisely happens around this tiny Italian island rarely reaches the public. Mainstream narratives instead tend to distort public opinion and inflame the debate.

While the EU plans its military operation to ‘disrupt human smuggling networks in the Southern Central Mediterranean’, this article aims to provide some much needed clarity on the present situation, based on my own direct knowledge of the island. Indeed, by understanding how the border system in Lampedusa actually functions, and the major interests at stake in running such a costly apparatus – both in terms of the human cost and the financial cost for EU taxpayers – it becomes easier to appreciate the role that Lampedusa plays within the broader EU external border regime.

The ‘concentric circles’ of the border at Lampedusa

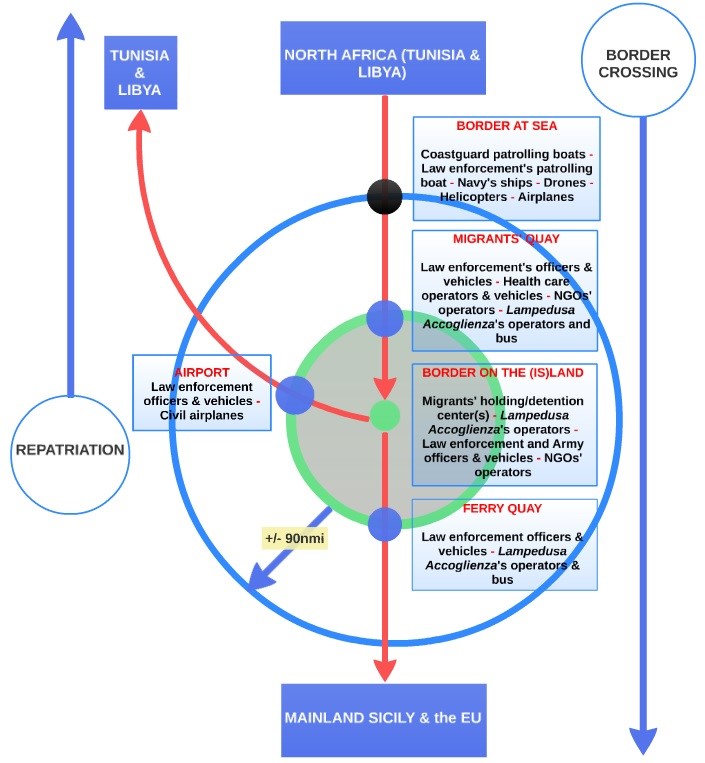

The EU’s external border structures in Lampedusa are complex. With the island at its core, its functions spread over a vast area, enclosing seawaters over a distance of tens of nautical miles. As such, the border can largely be divided into two areas: those areas at sea and those on land.

At sea, border operations develop along two major trajectories as migrants’ boats are first detected and then rescued. In terms of the present maritime external border at Lampedusa, the surveillance system relies on sophisticated electronic devices, large navy ships, drones, helicopters, intelligence staff deployed on the North African coast, coastguard boats, radar, satellites, soldiers, and law enforcement officials. However, migrant boats are also often located by fishermen and other civilians navigating the Sicilian Channel. Frequently migrants call for rescue and provide their coordinates.

Once boats are detected, the Italian navy and the other European navies operating in the area – mostly within the frame of Frontex operations – eventually rescue migrants. However, at times migrants have been simply (and illegally) pushed back to their original departure country. Fishermen and other civilians often take part in these highly risky operations. In general, all of these actions, from detection to rescuing, take place several miles away from Lampedusa: once migrants board a rescue boat they are then taken to the island.

On Lampedusa itself, there is the Favarolo quay: a gated dock where migrants are disembarked, including those that have died, and where medical aid will be delivered to those in need. From there, a bus takes migrants to the island’s holding centre. This is a constantly overcrowded facility where ‘hosts’ are often detained for months, even though the law states they should be deported to detention centres in mainland Sicily and the rest of Italy no later than 96 hours after arrival.

At the centre, if the internal management is the sole responsibility of private actors, numerous law enforcement officials manage security and surveillance. Once detention ends, migrants are deported away from the island. Although in the past direct flights have transferred migrants back to Libya and Tunisia from Lampedusa’s airport, in almost all cases migrants, accompanied by an escort of law enforcement officials, are now taken to mainland Sicily via the only ferry connecting the island with the rest of Italy.

Overall the border system can be conceived of as a form of ‘concentric circles’ with the aim of slowing down and steering migration, rather than stopping it completely. The figure below presents a visual representation of the system and its border functions as they spread across the island and the sea surrounding it.

Figure: Visual representation of the EU’s external border system at Lampedusa (click to enlarge)

Source: Compiled by the author

In addition to this complex border apparatus involving several different actors at a multitude of levels – local, regional, national, European and global – a variety of other stakeholders also converge around Lampedusa, given its status as one of the most iconic spots in the EU’s external border regime. Several naval and military actors operate in the area, with geostrategic calculations developing alongside the maintenance of the border regime.

The border system also entails sophisticated radar and surveillance technologies developed by major European – as well as non-European – defence and security corporations within the scope of an EU funded research project, the EU Security Research Programme. While the border at sea has become a notable commercial opportunity and a major geostrategic factor for national governments, the land-based detention system has also attracted the interest of a diverse range of actors. Private companies, Catholic organisations and cooperatives have all contributed to the running of the detention centre in exchange for daily fees of 30 to 50 euros per migrant provided by the Ministry of the Interior. This corresponds to a business that is now estimated to be worth millions of euros per year.

A purposeless and deadly system

Europe’s external border is therefore both a profitable business for many actors, and a deadly obstacle for others. Yet the precise rationale for the existence of the system and its associated costs remains debatable. The official justification cites the capacity to ‘combat more effectively terrorism, illegal immigration and human trafficking’; yet there is an absence of empirical data that confirms any relationship between illegal immigration and terrorism. A series of practical evaluations have also undermined the prevailing narrative in support of the current system.

Indeed, despite Lampedusa’s centrality in the construction and representation of Europe’s border regime, the island itself plays only a marginal – if not entirely irrelevant – role in terms of the overall presence of undocumented and illegal migrants in the EU. As Frontex note, the biggest entry route for those migrants who currently reside illegally in the EU has been international airports, with most of those having entered in possession of valid travel documents and a visa that has since expired.

Of those that did cross Europe’s external border without the necessary documentation, only a small proportion of them have actually entered via the maritime border, and many of them used routes other than the one through Lampedusa. The rest have traversed land borders. Nevertheless, the island remains top of the list of spending priorities for Frontex and this disproportionate level of attention becomes even more striking when one considers that the vast majority of the migrants passing through Lampedusa are genuine refugees.

If this was not enough, then travelling through the countless small-ports scattered along the southern Sicilian coast, one very quickly realises that migrants not only arrive at Lampedusa. Arrivals in these other ports are not only frequent, but have been happening for decades. What differs between those landing at other ports and those at Lampedusa is simply the level of media and political visibility. This underlines what many stakeholders on the ground already know to be true: that it is simply impossible to patrol such a vast maritime border so long as there remain countless ways to cross the Sicilian Channel and no technologies available to prevent the practice.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: MOAS / Darrin Zammit Lupi

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1H1YqUX

_________________________________

Giacomo Orsini – University of Essex

Giacomo Orsini – University of Essex

Giacomo Orsini is a PhD Candidate at the University of Essex.

Giacomo states:

“Overall the border system can be conceived of as a form of ‘concentric circles’ with the aim of slowing down and steering migration, rather than stopping it completely.”

Where is the evidence that Lampedusa – anything that the EU, Italy, Lampedusa itself has done or is doing is “slowing down” this evil people smuggling trade.

In fact it seems via the references Giacomo has provided that Italy was on the life saving and logical track back in 2005 by enforcing an immediate repatriation of people smuggling customers.

No wonder the Eu has the problems it has.

Tied up in a labyrinth of committees, no one in charge, fearful of some kind of embarrassment at the hands of the activists posing as judges in the various people smuggler friendly tribunals.

No wonder Thousands Have Died!

There is little doubt that Thousands more will die – as these nefarious characters enjoy the taxpayer funded salaries and booze and do their bit to ensure that Italy has no border controls. That the EU states have no border control. And that every domestic disaster on the African continent will ensure a green light for criminal people smuggler gangs to offer a product that they can seemingly guarantee – a passage to Europe.

That thousands will die enroute, in deserts and on the high seas, will make no difference to these highly principled activists.

Only Australia has shut down people smugglers.

Insofar as the pale copy of Australia’s success goes – here is the telling self declared recipe for failure that the EU military are about to embark upon their adventure with:

“The EUMC considers an indicative military End State

to be: the flow of migrants and smugglers activities have been significantly reduced. ”

Right from the word “Go” the EUMC is accpeting of failure.

What the Australian experience – on two separated occasions many years apart – we have done it twice – what the Australian experience has proved is that you must ensure a total denial of what these evil murdering people smugglers are offering. You must guarantee that if you arrive by irregular maritime means – you will NEVER be allowed to stay.

It’s that simple.

People smuggling CAN be beaten.

You need to operate a zero tolerance regime.

Detect at sea and return immediately by boat turn around or via the provision of lifeboats..

You are dealing with a one month problem there.

That’s all.

Sure, smuggling might be beaten, but at the cost of thousands of lives: they wont die at sea, so that European (or Australian) public will not have to deal with any eventual frustration or ethical dilemma. They will simply die in the countries from where they come from (and who cares of the non-refoulement principle right? Yes, not one of those ‘high principles’ activists like so much, but rather one of the main principle of international law). I’d say more: they can keep dying in those countries (Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, …) where Italy and other European countries (but also Australia) invest a lot in warfare may be using weapons produced by those same corporations that receive EU funds to develop border surveillance technology. Right. Good. But let me provide you with another option: you stop bombing countries here and there, you provide possibilities for refugees to apply for asylum also outside the EU (in member states embassies) and than take a regular flight to enter the EU. The money you save in costly but ineffective border control would go in integration policies that will reduce the eventual social costs, and the magic is done. The problem is solved, and may be people will learn how to be a little more human. And yet, for those who think/say that if you ‘open the door’ then everyone will come to Europe (or Australia), please show any evidence (as more important reports say exactly the opposite, not to mention interviews with actual refugees): after 8 years studying the issue on the ground, I could not see anything else but yet another manifestation of Eurocentric narcissism…

Giacomo, thanks for responding.

Sentence by sentence – word by word – here is where you are wrong!

“Sure, smuggling might be beaten” – sorry mate – this line should be “Sure, smuggling WILL be beaten…” – because Australia – facing similar circumstances to that of Europe has used a range of responses – not including refoulement – to stop the boats.

Not once Giacomo – but twice!

By two different governments separated by a killing Leftist Government who promised – hand over heart – that by relaxing the first successful Government’s Anti- People Smuggling Laws – the boats would not Re start.

They – the UN, The UNHCR, The OIM etc were proven wrong – and thousands were known to have died. Along with an unknown death toll lost without trace on these remote seas.

The policies you speak of were disproved in Australia.

And I’m sure you have spent months – if not years – studying the Australian experience. Right?

No?

You then make this totally unsubstantiated claim: “at the cost of thousands of lives: they wont die at sea, so that European (or Australian) public will not have to deal with any eventual frustration or ethical dilemma. They will simply die in the countries from where they come from”

Without a shadow or glimpse of any evidence.

Where is your evidence that stopping the boats would lead to loss of life?

List it here:

Not claims – assertions – just facts Giacomo! Can you prove your claim?

What is known is that by “putting the sugar [of access to a 1st world nation] on the table” that you will kill people. Via the provision of PULL factors.

You WILL kill people [ and the EU HAS killed people ] on the oceans, in the deserts and in the jungles via facilitating people smugglers business cases.

That is known – and provable.

Just ask the sailors pulling body parts of children out of the water. They’ll tell you.

What you have NOT proved is any link between stopping the boats and increasing deaths in 3rd World Nations.

You say: ” I’d say more: they can keep dying in those countries (Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, …) where Italy and other European countries ”

What has the above got to do with people smuggling?

You prove No Link!

Afghanistanis move over the border – when things get hot.

Then – when things cool off – they move back.

Where’s the link to people smuggling?

And Afghanistan is currently in the middle of a population explosion.

You then babble about the evils of corporations etc and then opine:

” Right. Good. But let me provide you with another option: you stop bombing countries here and there, you provide possibilities for refugees to apply for asylum also outside the EU (in member states embassies) and than take a regular flight to enter the EU. ”

Why?

There is NO reason to provide refugee flights to 1st world nations – high cost low population – 1st world nations from 3rd world nations!

There is and never has been any logical nor humanitarian reason to do so.

The strongest, smartest, most criminally corrupt individuals will self select for entry on the planes. Leaving behind their less able countrymen with even a lessor chance of fixing things.

Never, in the history of the UN, The UNHCR has such a proposal got up.

Never, in the history of the same – has any “regional solution” ever stopped the slave trade that is people smuggling.

You then go on with:

“The money you save in costly but ineffective border control would go in integration policies that will reduce the eventual social costs, and the magic is done.”

Well, the most costly and ineffective border controls are the ones that the UN, the UNHCR, the IOM etc – all the usual suspects – approve of.

They want navies sidetracked to perform large scale search and rescue in the Med.

They had that sort of operation going down here.

In the Med, your navies FACILITATE people smuggling.

Ruining forever the nations that they leave behind.

In Australia – our costs of running border protection have PLUMMETED!

Why? Because people smuggler boats do NOT set out for Australia.

Processing camps have been mothballed. Ships returned to port – or to training for the real reasons for their existence. And a skeleton fleet maintained.

The last boat intercepted was setting out for New Zealand – on a suicidal voyage – that would lead to the certain deaths of all those on board.

Narcissism! Given Italy’s and Germany’s relatively recent experience with quite evil dictatorships – the idea of a right wing coup to redress the “narcissism” as you put it – you may mean the popular discontent with the imposition of these policies on the national aspirations of the locals.

Given that – you’d best be careful.

You then state:

“And yet, for those who think/say that if you ‘open the door’ then everyone will come to Europe (or Australia), please show any evidence ”

Ok:

Click here:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/0/07/BoatArrivals.gif/400px-BoatArrivals.gif

And for the article itself, here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pacific_Solution

That wasn’t hard.

When the PULL factors are put on the table – the boats come. As they are coming in the MED.

When the PULL factors are taken off the table – and your only prospect as a so called refugee is placement in another 3rd World situation – then the boats stop.

Along with ANY shred of credibility for the arguments you So believe in.

There are lessons to be learned from the Australian case, but with respect I do see this kind of argument repeated dogmatically all over the internet and it’s pretty disingenuous to put it mildly. Last year, for instance, there were an estimated 54,000 asylum seekers boarding boats in Australia’s South-East Asian neighbourhood (about 15% of the global total) so the narrative that Australia’s border policies have prevented boats taking off full stop – in your words “When the PULL factors are taken off the table – and your only prospect as a so called refugee is placement in another 3rd World situation – then the boats stop” – is completely at odds with the evidence. People are still boarding boats in the region, they simply aren’t getting to Australia.

Conceptually speaking the argument also doesn’t hold much water. If it needs to be stated, the European neighbourhood includes countries that are warzones (Syria) and failed states where there is no possibility of anything approximating a normal life. Libya, where most of the boats set off for Italy, is in a state of chaos. Trying to “solve” the problem by conceiving it as simply being about the pull factor of Europe (and where the solution is simply preventing boats setting sail for Italy) is a pretty myopic perspective to put it mildly and ignores the “push” factors that drive people into boats in the first place. The goal isn’t to stop boats, it’s to stop people dying.

Either way this is a serious issue and ideologically-based polemics which posit that there’s some easy fix (whether it’s opening our borders or having an Australian-style zero tolerance approach) isn’t going to get us anywhere.

Brian, you have to be kidding?

Really?

“Last year, for instance, there were an estimated 54,000 asylum seekers boarding boats in Australia’s South-East Asian neighbourhood (about 15% of the global total) so the narrative that Australia’s border policies have prevented boats taking off full stop – in your words “When the PULL factors are taken off the table – and your only prospect as a so called refugee is placement in another 3rd World situation – then the boats stop” – is completely at odds with the evidence. People are still boarding boats in the region, they simply aren’t getting to Australia.”

Brian, here is a fact of life you might find unpleasant to contemplate:

The world is ruled by Nation States.

There is no Regional Government called “Australia’s South-East Asian Neighbourhood”.

This may come as a shock to you.

No other body sets immigration or enforceable border protection policies other than national governments.

I hope you can take it.

I can only assume that you are embarking upon some kind of misinformation campaign to push some kind of agenda.

Let’s then look at the 56,000.

If Indonesia followed Australia’s example – not one rohingya would try a boat trip to Aceh.

Why?

Well their boat would be intercepted at sea, towed back off the territorial waters of Myanmar and released. With instructions not to do it again.

One or two weeks of that response and Indonesia would never see a Myanmar rohingya again.

They too – would stop the boats.

What they have done is allowed them to land and then to ring family and friends to advise them to make the same trip.

Just as Iraqis and Afghanistanis were once doing when they reached Australia FROM Indonesia.

So your bogus reasoning Brian – is beyond the pale.

I say this because unlike most forms of propaganda – yours can have the result of maintaining a policy that kills people.

That’s something to think about.

Here in Australia, some politicians will go to their graves as the pollies who deceived the Australian population, got elected on the false premise that they wouldn’t kill people via restarting the people smuggling business.

They Lied. And thousands died. Because of them.

So be careful.

I do the same here, replying to each of the points you raised. Then, I guess, I will be fine continuing this (if we have to continue it) via email.

First: how do you know that ‘smuggling’ people to Australia does not take place anymore? As an illegal activity, it goes partly undetected. If you read my piece here on the blog, at the end I say that travelling the ports of southern Sicily there is plenty of boats used for migrants to reach the coast. I tell you more: if you ask law enforcement officials/border guards/coastguard, everyone tells you that tens/hundreds/thousands of people are ‘smuggled’ also in much smaller groups than the ones we are used to see taken to Lampedusa. They travel in private yachts, fishing vessels and so on. Talking about the topic with a UK border guard deployed in the Southern British border – the one facing the English Channel – he agreed with me exactly on this point. His first-hand experience tells him the same I am trying to tell you: there are indeed tens of small boats of any sort crossing the channel, each of them with few ‘undocumented people’ on board every day. Yet, there is simply NO WAY to control effectively all of them. There is no way to be in any small touristic port of the Southern British coast checking for each boat docking there at any time of day and night. As for the Sicilian channel, exactly the same applies. Fishing vessels take ‘smuggled’ people on board in international waters, and then take them on dryland. You can do the same with sailing boats navigating from Tunis to Palermo and so like. It is good business as far as once you get five people on board, you can easily make 20/25,000€. You can get these real figures only if you go on the ground, you observe carefully, and ask to stakeholders. As for the Australian case – that I never studied closely (and I never said I did) – I am not sure about the exact figures: I assume however it to be different from the Mediterranean case due the different seas (and the corresponding difficulties to cross it). However, in 2009 the Italian government claimed to have successfully implemented a ‘zero tolerance’ policy by involving Libyan and Tunisian forces in patrolling their shores from land. Only a few tens of people reached Lampedusa that year. However, boat migrants kept arriving directly to the Sicilian coast. The only difference was that neither politics nor media provided any visibility to them (and this is the grounded knowledge I am talking about: you can only know these things if you go to these places and dig into local press. And I did it).

Furthermore, Italy was condemned (see: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/sites/eng/pages/search.aspx?i=001-109231#{“itemid”:[“001-109231”]}) from the European Court of Human Rights also – and not only – for having violated the principle of no-refoulment. Again: asylum seekers means that you need to process their asylum applications (like it or not, it is an international obligation for European member states).

Concerning the ‘sugar’/PULL factor, as Brian said it is based on NO empirical data at all. No evidence whatsoever. Take the famous Mare Nostrum example. You have an increase of arrivals during this search and rescue operation right? Then, again, I ask you to consider smuggling for what it is: in fact an illegal activity that is hardly detected by authorities. You put more surveillance apparatuses in place, and you detect more people. That does not mean that a) more people than before are trying to cross the sea and b) no people keeps crossing the sea undetected (and this, I guess, answers your Wikipedia’s chart).

You have to understand the mechanics of the border (and I guess I tried to explain that in the first part of my post). If you have for instance four boats crossing simultaneously the sea at hundreds of nautical miles from each other, it literally takes hours to move rescuing forces from one boat to another: you simply cannot be on the four spots at once. On the other hand, if you refuse refugees who have entered by boat to apply for asylum, you will ‘certainly’ stop with those overcrowded smugglers’ boats we are used to see on TV. As I already said, however, this does not mean that you stop with people entering without the necessary documents by the sea.

As for the link between wars and smuggling, it is again something I expected to be self-evident, as far as those embarking on smugglers’ boat are refugees that flee wars/violence/climate disasters (again, based on empirics – that means checking those detained in Lampedusa, Melilla, Malta, …). Most people – as you said – ‘cross the border when the situation is hot, and go back when the situation gets better’. You do not realize that in such a way you are confirming exactly the opposite of your sugar/pull point raised few lines above. That is what most empirical data says: most people do not necessarily dream to go to Europe (or Australia) but rather to live a peaceful life close to their relatives and friends. All humans, not just those of the affluent world. In 2013, UNCHR (http://www.unhcr.org/5399a14f9.html) counted 51.2 million refugees in the world. Of them, only 360,000 applied for asylum in the eight richest member states of the EU – being that the 86% of the total number of applications in the EU for that year. In the same year, Pakistan, Iran, Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, Kenya, Chad, Ethiopia alone hosted 5.439.700 refugees. All countries neighboring a conflict or a violent dictatorship. Moreover, consider also as all these eight countries together sum one fifth of the EU gross domestic product, but host 136 times more refugees than the whole EU does. It seems that there are the possibilities for Europe to provide better assistance and integration policies for many more asylum seekers.

As for processing applications outside the EU, this is actually on the table from LONG TIME. Just check it out. If you cannot find anything yourself, let me know and I will be happy to send you as many links as you like/need/want. If you combine this proposal with empirical data concerning refugees’ population, you might end out realizing that those who would apply will be the same that are trying to make it by boat today. You must have clear that as for Lampedusa (but also Malta) those who cross the sea by boat are for the vast majority relatively well-of people in their counties of origin, and who have the money to go into these very expensive and risky trips. Often they have relatives already residing in the EU – that is the main reason why they want to get there. Moreover, check about European countries’ policies of the past, for instance with Latin Americans political refugees from Chile. Governments – the Dutch one among others – went to refugees’ camps in Argentina asking for people willing to come to Europe. Not too much social harm. Not even millions of people moving to Netherlands. Also, just to make it clear: when I speak about the flights I did not meant that anyone has to pay the ticket for anyone else. My point is rather different. If you have 3-5,000€ to cross the Mediterranean by boat, you will probably have 300€ to take your flight from Istanbul/Beirut to Milan/Berlin/anywhere else.

Of course, you can ignore all these evidences and keep claiming that such a small percentage of people arriving in Europe (or Australia) because of wars &/or dictatorships that EU countries (or Australia) might have supported in one way or another, do not deserve to decide where they want to live their lives peacefully. That is understandable, and I am sure you can find plenty of rationales to justify it. I guess, however, that it has to do more with personal ethics and values (or the lack of them) rather than setting and implementing effective policies capable to ensure social peace and prosperity.

As for narcissism and the recent German and Italian experience with dictatorships related to the risk of having a few thousands of people fleeing war settling safely within half billion people living in the EU: well, again, I cannot see your point. The threat and social anxieties related to these arrivals comes from the DISPROPORTIONATE use of security apparatuses and discourses to address what it is NOT a security issue – for all the reasons listed above – but rather a humanitarian one. Again, if you need references to academic works on this matter, just let me know: I have tons to send to you. The public is very hardly reached by correct figures as the debate is politicized and media seem to have little interest in making certain information circulating. What I find narcissist is to think that the entire world is eager to come living in Europe (or Australia): data do not provide any evidence again. My personal interviews with refugees and migrants do not confirm that neither. Of course, it is cool to think that we live in the best place of the world: it also works perfectly in order to enhance EU or Australian national/supranational identities. Yet, again, it is simply not true.

One last point to answer Brian’s point about the ‘easy fix’. Opening borders by providing easier access to visa, means that people will enter regularly. If they enter regularly, it means that people will enter as the 90% of those residing without the necessary documents in the EU are doing today (overstayers). Thus, to allow that 10% more would not necessarily lead to social or political disaster, while it would allow saving a lot of money in pointless border control that could be reinvested in integration policies/services to migrants, refugees and citizens. Moreover, if someone enters regularly, it will be much easier to get personal data and then her/his identity. This means that social control and law enforcement will be much easier to organize and effectively implement.

@Frank

With respect, you do seem to have a fondness for grandstanding irately whenever anyone counters one of your points. I’ve quoted you directly. You clearly and explicitly stated that by removing the “pull” factor of a 1st world country the boats would stop. Here is your exact quote, word for word:

“When the PULL factors are taken off the table – and your only prospect as a so called refugee is placement in another 3rd World situation – then the boats stop”

I’m telling you that this simply isn’t what happened in the case of Australia. There are still thousands of people boarding boats in the region despite Australia’s policies. Instead of taking ownership for what you’ve said you’ve simply ignored it and started to make an entirely different point – that Australia isn’t responsible for what happens elsewhere in the region and that it’s all Indonesia’s fault in any case because if they just acted like Australia then the boats might stop (Indonesia not being a 1st world country, if we need to state the obvious).

Worse you seem to have littered your response with ranting and raving about “propaganda” when I merely took you at face value on what you said and illustrated precisely why it was wrong. Your original comment was clearly misleading – I suggest taking ownership of that and responding in a reasonable, mature way.