The governing centre-right coalition in Portugal won parliamentary elections on 4 October, but lost its majority in the Portuguese parliament. Luís de Sousa and Fernando Casal Bértoa assess what the results mean for the country’s party system. They write that Portugal has had an exceptionally stable party system in recent years and that this trend has continued, despite the financial crisis badly damaging the Portuguese economy. Nevertheless, there are high levels of disaffection among citizens, evident in the election’s record low turnout.

The governing centre-right coalition in Portugal won parliamentary elections on 4 October, but lost its majority in the Portuguese parliament. Luís de Sousa and Fernando Casal Bértoa assess what the results mean for the country’s party system. They write that Portugal has had an exceptionally stable party system in recent years and that this trend has continued, despite the financial crisis badly damaging the Portuguese economy. Nevertheless, there are high levels of disaffection among citizens, evident in the election’s record low turnout.

On the morning of 5 October, the 115th birthday of the Portuguese Republic – one of the bank holidays that has been eliminated by the country’s government during the crisis period – Portuguese citizens woke-up to a rainy autumn day with a taste of sweet and sour in their mouths.

Portugal re-elected the centre-right Portugal Ahead coalition formed by the ruling Social Democrats (PSD) and Christian Democrats (CDS/PP), the parties responsible for negotiating and implementing the country’s bailout. The question on everybody’s mind is why Portuguese voters did not choose to sanction at the ballot box the parties responsible for implementing austerity measures and for the hardship that has afflicted Portugal over the last four years.

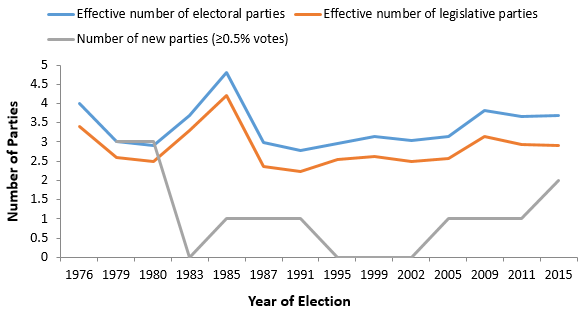

Moreover, why, in clear contrast to other countries such as Italy, Greece and Spain, where austerity policies have helped new parties to score electoral successes, did no new party manage to enter the Portuguese parliament? In fact, the stability of the Portuguese party system is so remarkable that the post-authoritarian history of Portugal’s party politics can still be told with reference to no more than four or five party-names: the Socialist Party (PS), the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) and the Left Bloc (B.E.), together with the two aforementioned political formations. This picture is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Portuguese parties in elections in Portugal (1976-2015)

Source: whogoverns.eu

Answering the above questions is far from straightforward, given voters have demonstrated decidedly mixed feelings over the government’s management of the economy. The results of the election show a divided electorate when it comes to blaming and punishing the government for austerity. As has been demonstrated elsewhere, this is partly to do with the general perception that the Portuguese government has a limited margin for manoeuvre, with restricted capacity to take decisions autonomously from global economic trends or the will of larger countries.

Indeed size played into the hands of the governing coalition: while it is true that the Portuguese economy suffers from a lack of buffers and leverage to respond to external risks; it is also true that the smaller the country, the less likely it is that its citizens will make their governments solely responsible for the negative repercussions of economic conditionality.

The results were a clear-cut victory for the centre-right coalition, but not a landslide victory and this will raise some doubts regarding future governability. The incumbent coalition was 12 seats short of an absolute majority in parliament: with four seats still to be determined from overseas votes, the centre-right won 104 seats against a total of 121 seats from the three centre-left parties (PS, PCP and B.E.). This means the centre-right coalition will have to govern with a centre-left majority in parliament. However, whereas coalition platforms have been possible on the right of the political spectrum, on the left side, these have not been able to obtain until now.

The centre-right coalition will be invited by the President of the Republic to form a government, but it will most likely suffer pressure from the centre-left when adopting major structural reforms, such as additional pension cuts and reductions to social benefits. Whilst the government coalition proudly claimed that they had gone way beyond what had initially been agreed with Portugal’s international creditors, as an attempt to send a positive sign to the financial markets and distance itself from the Greek turmoil, such unilateralism is less likely to happen during this legislature.

The centre-right coalition knows that it needs to negotiate with the Socialists if it wants to get its budget approved in parliament. There are a number of key measures regarding job creation/protection and corporate responsibility in the electoral manifesto of the Socialist party that may be acceptable to the new government. The need to create conditions for governability may have immediate implications regarding the new cabinet’s formation. The coalition could opt to refresh its team by inviting a few consensual figures for key portfolios, but this seems highly unlikely in the early stages of the new government.

Division on the left

The space for cross-party agreements on legislative matters will also depend on who takes over the leadership of the Socialist party following António Costa’s electoral defeat. The left has veto capacity, but the likelihood of forming a common front is low due to the weight of history and the ideological distance between the moderate Socialist party and the more ‘radical left’ parties, in particular regarding Portugal’s obligations towards international creditors and its future in the euro. Therefore despite the fact that an overwhelming majority of voters support the idea of a centre-left coalition, this is not expressed in the views of left-wing party elites, particularly the communists (as forthcoming research by André Freire and his co-authors demonstrates).

The economic crisis has not only increased polarisation of the party system regarding socio-economic issues, it has also shifted electoral competition to the left of the spectrum. The opinion polls carried out prior to the elections sent out clear trends to both the contenders and the voters. The centre-right capitalised on the slightly positive economic upturn that started to be experienced during the second term of the legislature and were able to contain the loss of discontented traditional voters, affected by austerity measures, to the left.

Facing fierce criticism from segments of its party elites for being obtusely ideological in the way it addressed (welfare) state reforms, the Social Democrat leadership reminded the electorate, on various occasions, of its social justice foundations, in an attempt to reframe its neoliberal façade. Meanwhile the Socialist leadership failed to win votes from the centre with its worn-out “bota-abaixo” (bashing) discourse that did little “to regain the confidence” of the undecided median voter (the Socialists’ campaign slogan), who opted largely for abstention. It also lost votes to the left (mainly Bloco de Esquerda).

Ultimately, the Socialist party failed to capitalise on discontent with the incumbent for a number of reasons: the mediatisation of the Socrates affair; a negative perception of the PS’s legacy in handling the economy – in particular, the high public debt to GDP ratio, rising unemployment figures and clientele-driven public investment; a few tactical mistakes (such as a blunder involving campaign posters) along the way; and the contestation of the party leadership prior to the elections, which did not go down well with a few traditional voters.

For the first time in the history of Portuguese democracy, a party leader that has won two consecutive elections, during an adverse political context and with little support from party elites, saw its leadership contested internally on the grounds that he had not been able to capitalise on the overall mood of discontent with the incumbent. Replacing António José Seguro, who had a more consensus-building posture than Costa, a few months away from the general elections, was an unwise move, as the campaign dynamics finally proved.

A stable party system, but falling satisfaction with democracy

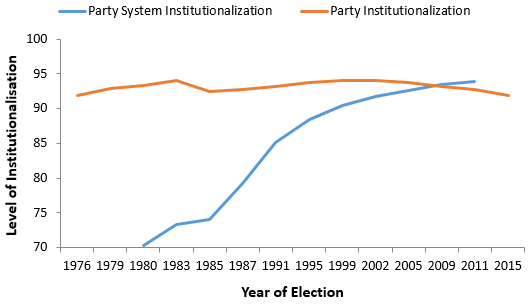

Since 1987, the Portuguese party system, characterised by relatively low levels of parliamentary fragmentation and electoral volatility as well as the political alternation between the two main parties (the Socialist Party and the PSD) in either stable single-party or two-party coalition majorities, has remained extremely stable. Figure 2 shows a representation of this using a measure of ‘party system institutionalisation’: defined as ‘the process by which the patterns of interaction among political parties become routine, predictable and stable over time’.

Figure 2: Party system institutionalisation in Portugal (1976-2015)

Note: For a full explanation of the calculation of party system institutionalisation, see here. Source: whogoverns.eu

This being said, in recent years (particularly since 2009), aggregate satisfaction with democracy has ‘plunged to the lowest levels ever recorded’ in the country and political participation, in all its forms, is well below the average of other EU countries. Not surprisingly, the 2015 elections registered a record low turnout of 56.9 per cent, only comparable to other new EU democracies in post-communist Europe such as Poland, Lithuania and Romania.

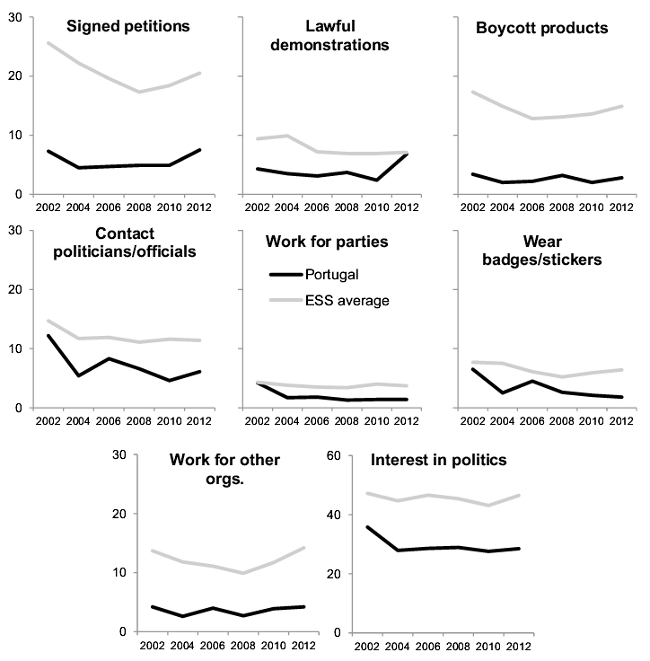

Contrary to what has happened in other southern European democracies, the economic crisis has not ignited citizens’ engagement with political issues. As a recent study puts it: ‘With the exception of protest activities, most types of political participation acts do not show relevant increases in prevalence. In other words, the conceivable pressure towards greater involvement in politics brought about by the dissatisfaction with the economic and political conditions seems to have been largely countervailed by the resilient syndrome of political disaffection that still prevails among the Portuguese citizenry’. This is evident in European Social Survey data on political participation and interest in politics in Portugal. In every category shown in Figure 3, Portugal’s value (dark line) is below the European average (lighter line).

Figure 3: How political participation and interest in politics in Portugal compares with European average (percentage of citizens)

Source: De Sousa et al. (2014)

These elections brought to the fore a clear division in Portuguese society that may regain intensity and momentum during the next presidential elections and which has clear implications for the future leadership of the Socialist party. On social media, reactions to the result can be divided into two camps: on the left, comments highlight a sense of bitterness and disillusionment at the short memory of Portuguese voters, who are claimed to suffer from a kind of Stockholm syndrome; in contrast right-of-centre supporters claim that voters are not stupid, and have rewarded the government for timid yet clear signs of economic recovery.

Beneath these superficial tensions, which are common in polarised party systems and highly disputed electoral contests, lies a more deep-rooted ideological cleavage: between those who are supportive of the welfare state as a catalyser of economic and social progress, and those who believe that the country’s competitiveness can only be achieved by rolling back the state.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1L8LbQA

_________________________________

Luís de Sousa – Universidade de Aveiro

Luís de Sousa is a Professor at Universidade de Aveiro in Aveiro, Portugal.

Fernando Casal Bértoa – University of Nottingham

Fernando Casal Bértoa is a Research Fellow at the University of Nottingham.

1) You say that PS lost votes to BE. But in fact PS increased votes relatively to the 2015 elections. It was PaF that lost 700.000 votes. Do you have a vote transfer model?

2) why do you say AJSeguro is more of a connsensus-buikder than ACosta? ACosra was quite able to work with opposition parties when he was mayor of Lisboa

3) If you think a bit and use you maths skills you will find out a correlation between the increase in absenteism and the increase of emigration – which is a form of discotent you ignore in this article

Paulo Costa