Switzerland held federal elections on 18 October, with the conservative Swiss People’s Party winning the largest share of the votes. Daniel Bochsler, Marlène Gerber and David Zumbach write that while the increase in vote share for the Swiss People’s Party was relatively limited, the party managed to significantly increase the number of seats it holds in Switzerland’s lower house of parliament, the National Council. Nevertheless, the party is unlikely to make substantial gains in the country’s upper house, the Senate, as it traditionally struggles under the two-round electoral system used in Senate elections.

Switzerland held federal elections on 18 October, with the conservative Swiss People’s Party winning the largest share of the votes. Daniel Bochsler, Marlène Gerber and David Zumbach write that while the increase in vote share for the Swiss People’s Party was relatively limited, the party managed to significantly increase the number of seats it holds in Switzerland’s lower house of parliament, the National Council. Nevertheless, the party is unlikely to make substantial gains in the country’s upper house, the Senate, as it traditionally struggles under the two-round electoral system used in Senate elections.

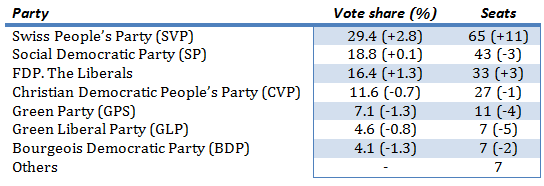

The main winner of the Swiss elections on 18 October was undoubtedly the national conservative Swiss People’s Party (SVP) which saw its vote share increase by 2.8 per cent, reaching a historical high of 29.4 per cent, resulting in 65 seats – a net gain of 11 seats in the country’s lower house, the National Council, which has 200 seats in total.

On the other side of the political spectrum, the Greens (-1.3 per cent) and the Social Democrats (SP) (+0.1 per cent) had to give up four and three seats, respectively, with the consequence that the two leftist parties, for the very first time, hold less seats (54) than the SVP (65). Meanwhile the Liberal Party (FDP) – representing an economic conservative position – increased their vote share for the first time in 36 years (+1.3 per cent; +3 seats), whereas the Christian Democrats (CVP) did not manage to halt their decline (-0.7 per cent; -1 seat). Two small, and very young parties of the centre-right, the Bourgeois Democratic Party (BDP) and the Green Liberal Party (GLP) suffered losses of -1.3 per cent and 0.8 per cent, the latter losing 5 out of 12 seats in parliament.

Table: Results of the 2015 Swiss federal elections (National Council)

Note: Swiss parties often have more than one abbreviation due to the use of different languages. For more information on the parties see: Swiss People’s Party (SVP); Social Democratic Party (SP); FDP.The Liberals; Christian Democratic People’s Party (CVP); Green Party (GPS); Green Liberal Party (GLP); Bourgeois Democratic Party (BDP).

Gains and losses of votes and seats were highly disproportional, given most of the 26 electoral districts (equal to the cantons) are very small. Only seven districts count 10 or more seats. While the ‘apparentment’ system in Switzerland, under which parties can specify electoral alliances, allows parties partly to escape the electoral system bias against small competitors; such alliances can also foster discrepancies between seat allocation and vote distribution.

In the National Council, the conservative FDP and SVP (jointly with two tiny parties) now occupy a razor-thin majority of 101 out of 200 seats. Switzerland’s upper house, the Senate, is expected to remain stable once the full results are determined, so the two right-wing parties need to rely on the Christian Democrats for a majority.

The upper house is elected in most cantons by a two-round majority vote, leading to an overrepresentation of the FDP, the CVP, and in recent years also the Social Democrats, while the SVP struggles to win seats under this system, currently holding only five out of 46 seats. A definitive assessment will only be possible after the second round of elections have taken place in 12 out of 26 cantons by the end of November.

Electoral campaign: personality over substance?

The election campaign was one of the most expensive campaigns in Swiss history, but has also been regarded as lacking in substantive content. Campaigning events and communications via social media typically saw personality and style trump substance. This style of campaigning was epitomised by a music video from the SVP, ‘Welcome to SVP’, entering the official Swiss charts.

While in the previous elections in 2011, almost every party pursued its own popular initiative, which allows citizens to suggest changes to the law, it was only the SVP that launched one in 2015: a self-determination initiative demanding that the Swiss Constitution stands above international law. However, given that other parties’ initiatives were rejected at the ballot box or even failed at the stage of signature collection, this change in strategy may be understandable.

The big exception to these failed initiatives was the referendum proposed by the SVP and held in February 2014 on reducing immigration, which narrowly passed with the support of 50.3 per cent of voters and 17 out of the 26 cantons. In order to implement the popular initiative, the Federal Council was assigned to renegotiate Switzerland’s existing agreement with the EU on free movement of persons – a still ongoing process.

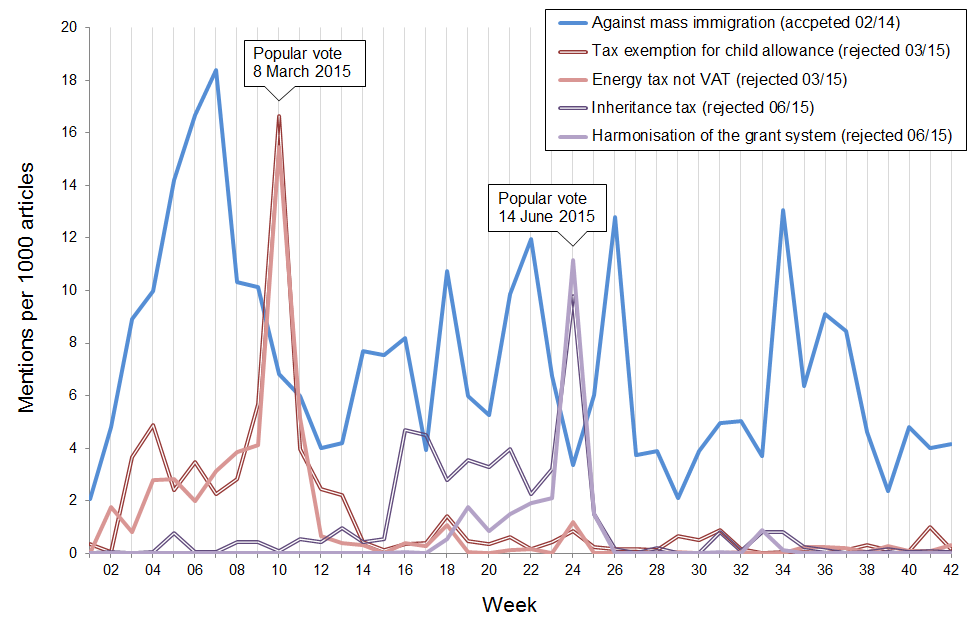

Given the significance for Switzerland of its bilateral treaties with the EU, it is surprising how little the issue was brought up by parties in the run-up to the elections, as shown by an analysis of parties’ press releases. The initiative and its potential effects, in turn, still receive enormous attention by the media – even more so than popular initiatives which have actually been subject to a vote in 2015, as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1: The presence of popular initiatives in Swiss online media (2015)

Note: Analysis based on automated information retrieval of 82 Swiss online news resources (59 in German, 14 in French, and 9 in Italian language). Source: Année politique suisse

In addition, the SVP reached omnipresence in terms of advertisements placed in print media. Together with the FDP, they accounted for about 60 per cent of party adverts published in newspapers (30 per cent each), including expensive nation-wide campaign ads. International organisations have repeatedly expressed concern over the absence of transparency in campaign funding. Campaigns are funded through private donations and membership fees.

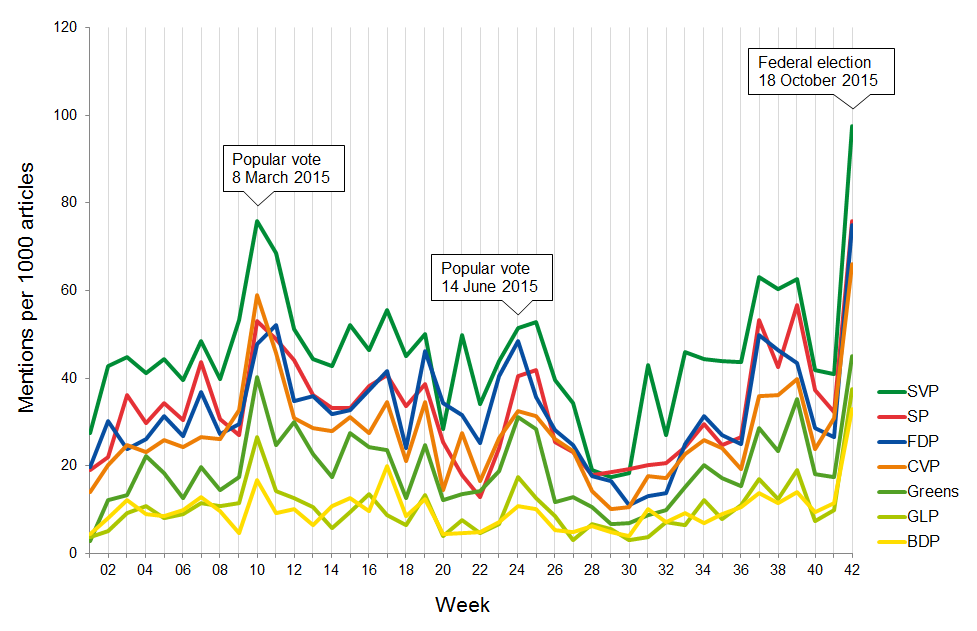

In the campaign, the main issue emphasised by the SVP was their opposition to migration, refugees and EU integration; whereas the FDP largely emphasised economic issues. The Social Democrats campaigned for social welfare, especially against cuts to the pension system. While a party can influence their visibility in terms of campaign adverts and a deliberate campaign strategy funded by available financial means, they are not in direct control of their presence in the media. However, as Figure 2 shows, the media accredits attention more or less in relation to a party’s strength, with the SVP receiving the bulk of coverage.

Figure 2: The presence of parties in Swiss online media (2015)

Note: Analysis based on automated information retrieval of 82 Swiss online news resources (59 in German, 14 in French, and 9 in Italian language). Source: Année politique suisse

In a joint meeting on 9 December, the two houses of parliament will sequentially elect each of the seven government ministers by majority vote. Since 1943 (with an interruption between 1953-9), the government has been composed of the four largest parties, although one minister has been expelled from her own party.

So far, out of seven seats, this seat is the only one which is disputed. Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf of the SVP was elected to government in 2007, although not as an official party candidate, which is not uncommon. She was subsequently expelled by her own party, leading to the formation of a small spin-off party, the BDP. Now, the FDP as well as the SVP are urging parliament not to re-elect her.

They argue that the BDP, with only 7 seats in the lower house, does not carry sufficient weight for representation in government. Her supporters, including the left and the Christian Democrats, refer to an iron rule, according to which ministers should only be fired after major scandals or bad performance in office. However, they also fear that the BDP’s seat will be taken over by the SVP, which would shift the balance toward a government more dominated by the FDP and SVP.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: A version of this article appears at whogoverns.eu. The article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature photo credit: bigbirdz (CC BY 2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1GwPOHv

_________________________________

Daniel Bochsler – University of Zurich

Daniel Bochsler – University of Zurich

Daniel Bochsler is Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics and Democratisation at the University of Zurich. He works on ethnic politics, elections, and democratisation.

–

Marlène Gerber – University of Bern

Marlène Gerber – University of Bern

Marlène Gerber is Deputy Director of the Swiss Political Yearbook (Année Politique Suisse) at the University of Bern. Her research interests include deliberation, direct democracy and political communication.

David Zumbach – University of Bern

David Zumbach – University of Bern

David Zumbach is Research Assistant at the University of Bern. His research focuses on Swiss economic policies. He is also interested in voting behavior and political competition.

It’s a great move in the right direction for Switzerland.