After the failure of the South Stream pipeline project, is Russia’s energy influence over Europe diminishing? Jarosław Wiśniewski argues that it is vital to recognise the role of foreign and security politics in energy projects, rather than simply focusing on their economic effects. He writes that energy initiatives have been used by Russia to create particular geopolitical narratives, which is now evident in the way Gazprom is promoting a planned new pipeline, ‘Nord Stream 2’, between Russia and Germany.

After the failure of the South Stream pipeline project, is Russia’s energy influence over Europe diminishing? Jarosław Wiśniewski argues that it is vital to recognise the role of foreign and security politics in energy projects, rather than simply focusing on their economic effects. He writes that energy initiatives have been used by Russia to create particular geopolitical narratives, which is now evident in the way Gazprom is promoting a planned new pipeline, ‘Nord Stream 2’, between Russia and Germany.

Several factors have led observers to believe that Moscow’s dominance over European energy markets is bound to take a downward turn: the collapse of the South Stream pipeline, the economic sanctions imposed on Russia, the American shale gas revolution, and the increased availability of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Such reflections, however, ignore that energy has long ceased to be merely economy-oriented, and that energy measures are increasingly becoming part and parcel of foreign and security policies.

Seen through the lens of an economist, various energy initiatives can indeed appear unprofitable. This is why constructing a narrative, elaborating a certain way of ‘explaining’ or ‘selling’ the story, is becoming even more important than engaging in discussions about the economic viability of various projects. Next to the long list of agreements, memoranda, deals and counter-deals, the history of EU-Russia relations is, ultimately, a history of competing narratives, and each initiative therefore requires a certain storyline. The term ‘storyline’ refers to the events that a piece of prose conveys, be they real or fictional. These events are usually neither good nor bad in themselves.

Let us take the example of the 2006 energy crisis between Russia and Ukraine, when Russia cut the supply of gas flowing through the pipelines across the Ukrainian territory. The events themselves did not tell the observer anything about Russia’s motives, i.e. was there any reason behind it? Was it somehow justified? The story in itself refers to the basic event. The meaning is attached to it through the art of storytelling, and the starting point is the plot. Coming up with a plot is a relatively simple exercise.

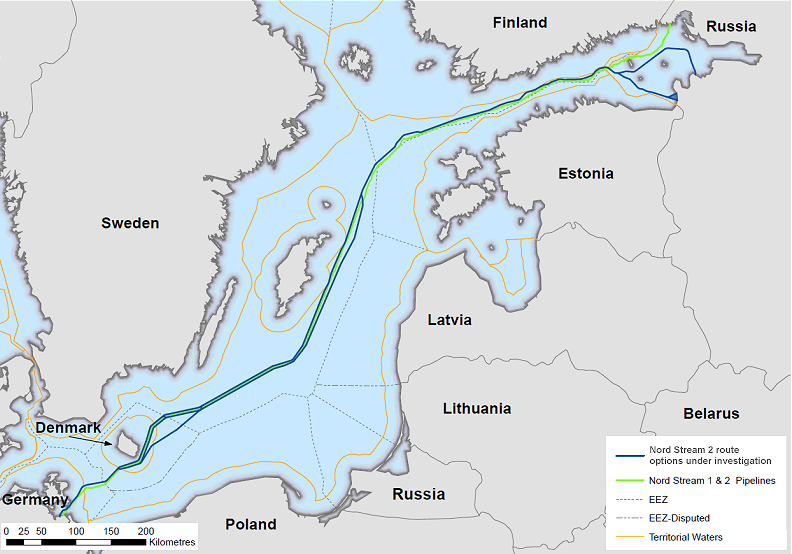

A recent case in point to consider is the latest virtual pipeline, Nord Stream 2. This project was agreed upon during the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok on 4 September 2015, when representatives of Gazprom, BASF, E.ON, ENGIE, OMV and Shell signed a Shareholders’ Agreement on the implementation of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline nominally to ‘enhance supply of natural gas to the European Union’s market’. The agreement foresees the construction of two pipelines (aggregate capacity of 55 bcm per annum) running under the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany. According to Gazprom’s CEO Alexey Miller, the plan is to make Nord Stream 2 operational by the end of 2019.

Figure: Map of the proposed Nord Stream 2 pipeline route

Note: Image reproduced from the project’s official website.

The creation of the storyline follows these five steps. First of all we need actors, ideally both good (protagonist: the consortium made of the Russian energy suppliers and the EU energy recipients) and evil (antagonist: the transit countries, i.e. Ukrainians and their supporters). The protagonist must be confronted with a problem.

Second, the protagonist needs to have the willingness or motivation to act and to be ready to make ‘difficult’ decisions in order to solve the ‘problem’. The Nord Stream 2 website provides a very neat outline of the problem, defined as follows: ‘the EU needs secure gas resources in the long term in order to ensure global industrial competitiveness and meet domestic demand’. It also sets out the solution: ‘as a European neighbour with some of the world’s largest known reserves, Russia is a key supplier of natural gas to Europe’.

Third, the story needs to have a certain time frame. It requires a clear beginning, as well as a vision of when it will end. We find a temporal indications in the statement: ‘the overall gas demand in the European Union in the coming decades can only be met by further increasing imports from outside the EU’.

Fourth, a simple story has to be linear. Using flashbacks, however, can help shape the protagonist (Russia as a reliable supplier with a strong track record; ‘successful Nord Stream’). To be convincing, the story also needs obstacles, such as a need for energy and the need for ‘reliable and secure transport options’, i.e. bypassing unreliable transit countries (read: Ukraine). It needs challenges the protagonist needs to face in order to solve the problem.

Finally, the story needs a conclusion, a moral, which is here articulated as ‘a long-term solution for the EU’s energy security’. The storyteller has to pay careful attention to the language used. It needs to be clear and unambiguous, plainly suggesting who is the hero and who is the villain. In this case, some of the key elements that require a very precise articulation are: Russia as a reliable partner; the successful past cooperation; the use of the keyword ‘diversification’ in a way that suggests the diversification of routes, and not of the sources.

In the end what is produced is a narrative, a certain (subjective) account of connected events. This is a specific sequence, which has its starting point, a flow, and finally has an ending; but it is a narrative that is highly politicised. The Russian side however claims otherwise, accusing Nord Stream 2 opponents of the politicisation of the debate.

The most important aspect here is indeed language, and specifically the careful use of vocabulary. One of the most frequently used words is ‘geopolitics’. Even though the use of this word has nothing (or very little) to do with the actual academic concept, it is nevertheless an important keyword that allows the storytellers to escape stricter scrutiny, which is precisely what the advocates of Nord Stream 2 are trying to achieve.

The potential success of this narrative is highly debatable. Nord Stream 2 will probably be blocked under the existing EU competition rules, as already happened in the case of South Stream. It does however seem to exert a certain influence over political decision-makers, who have, in certain cases, used it as an excuse in existing domestic feuds, as the discord over this issue between the CDU and SPD in Germany clearly shows. It has also been positively received by some experts: a paper by the Jacques Delors Institute argued that “this could be a strategic moment to strike a comprehensive EU-Russia transit agreement on a coherent regime for all Russian import pipelines to the EU, or at least find individual solutions for every transit corridor”.

Opponents of the pipeline have focused on the absence of an economic justification for the project and on its irrelevance to EU policy goals. In his speech in October 2015, the EU’s energy commissioner Arias Cañete firmly questioned Nord Stream 2’s ability to respond to the policy objective of diversification of routes and sources: “as I said before, there is overcapacity for the transport of gas from Russia. For these reasons the Nord Stream 2 project cannot ever become a project of common interest. It cannot ever benefit from EU financing or EU support.”

Russia’s assertiveness is therefore not only seen in its actions, but is also visible in its narratives. These positions are increasingly clashing with those of the West, as Judy Dempsey has recently observed. Nord Stream 2 is a great example of how a very basic, and convincing storyline can be built and promoted.

Pipeline narratives are a part of Russia’s information warfare, as analysed by OSW’s Joanna Darczewska. In her case study focused on ‘the Crimean operation’, Darczewska argued that the information warfare’s “distinctive features are language (the language of emotions and judgments, and not of facts), content (compliance with the Kremlin’s official propaganda) and function (discrediting the opponent)”. This is hardly new or innovative, and has a mixed success rate; most recently, a failure in the South Stream case, and a probable failure of Nord Stream 2 as well. But it is undoubtedly set to continue.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: bit.ly/1KWXU9p

_________________________________

Jarosław Wiśniewski

Jarosław Wiśniewski

Jarosław Wiśniewski is an academic and political analyst who specializes in international security and European politics. He holds a PhD in European Studies from King’s College London, as well as master’s degrees from University College London and the University of Wrocław, Poland. Throughout his career, he has worked as a consultant for the European Commission, Council of Europe, British Council as well as a number of European civil society organisations and various public and private institutions in the EU and in South East Europe: in Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia, and Serbia among others. You can follow him on Twitter @jarwisniewski