How can fathers push for more gender equality? Monika Queisser, Willem Adema and Chris Clarke write that in spite of an increasing number of countries granting parental leave, the number of fathers making use of these rights is still very low. They point out that financial considerations are powerful factors in making leave decisions, as women still make considerably less money than men. This is not, however, the only impediment: prejudices and cultural pressure also play a crucial role and if this picture is to change it will require greater efforts from both employers and fathers themselves.

Prince William did it, Justin Timberlake did it, and so did David Cameron and Mark Zuckerberg. All four took paternity leave to spend time with babies George, Charlotte, Silas, Florence and Max. These trailblazers are great role models in combining family and work – at least when a new baby arrives – but men around the world are still too slow in following their example. And this despite the fact that more than half of OECD countries grant fathers paid paternity leave when a child is born; and paid parental leave, i.e. a longer period of job-protected leave open to both parents, is also available in more and more countries.

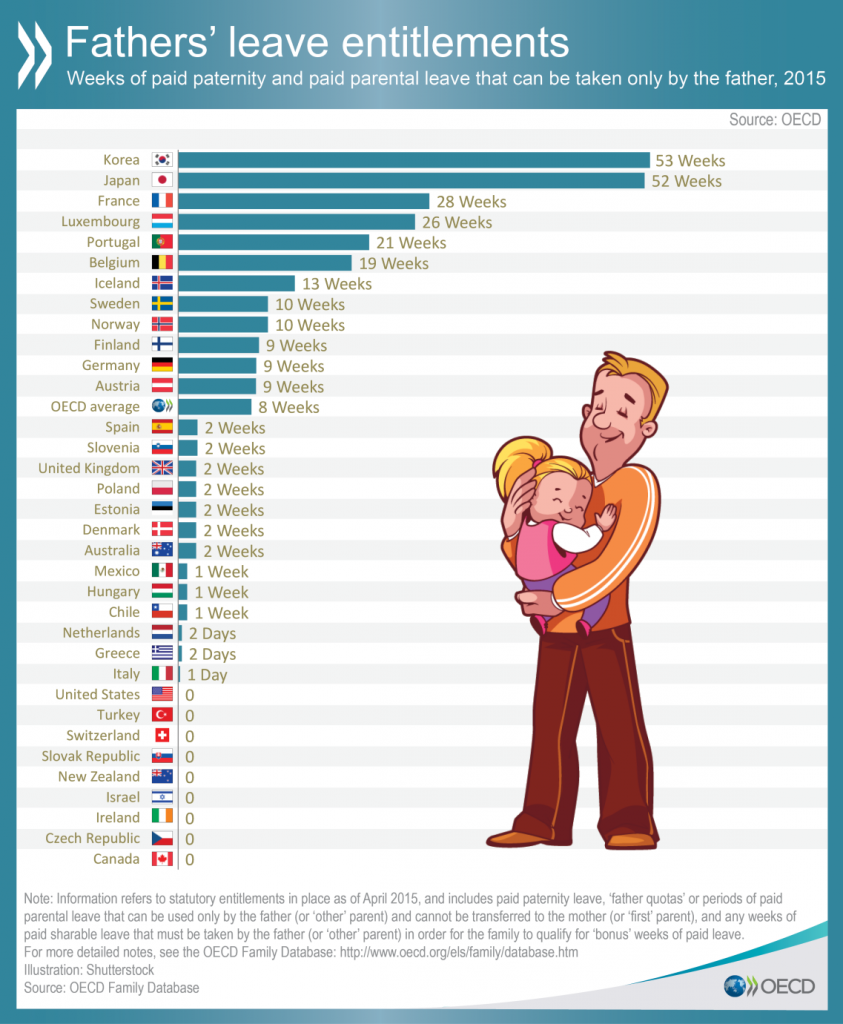

Parental leave for fathers typically lasts between two and three months and comes in different forms. Most common are “daddy quotas”, or specific portions of paid leave reserved for the father only. Some countries offer “bonus periods”, meaning that a couple may qualify for extra weeks of paid leave if the father uses up a certain period of a sharable leave. Other countries simply provide both parents with their own individual entitlement with no sharable period at all. So, in theory, more dads could be at home taking care of their kids and making it easier for both the mothers and themselves to live up to the expectations of babies and bosses.

The reality, however, looks very different. Fathers usually take a few days off right after the birth of a baby, but only the most committed and bravest use their right to longer parental leave. In many countries, fathers account for less than 20 per cent of those taking paid parental leave. Scandinavian and Portuguese men are more progressive: their share among paid parental leave users goes up to 40 per cent or more. Fathers in Australia, the Czech Republic and Poland, by contrast, shun parental leave; only about one in fifty paid leave takers is male. The most generous leave entitlements exist in Japan and Korea: a full year of paid leave is reserved just for the father – but very few men take advantage of it.

Figure 1: Fathers’ leave entitlements

Source: OECD

Why are we seeing so little movement in breaking up traditional gender roles? We are told that Generations X,Y and Z are looking for better balance of work and family life. So why are young fathers not even taking the days to which they are legally entitled?

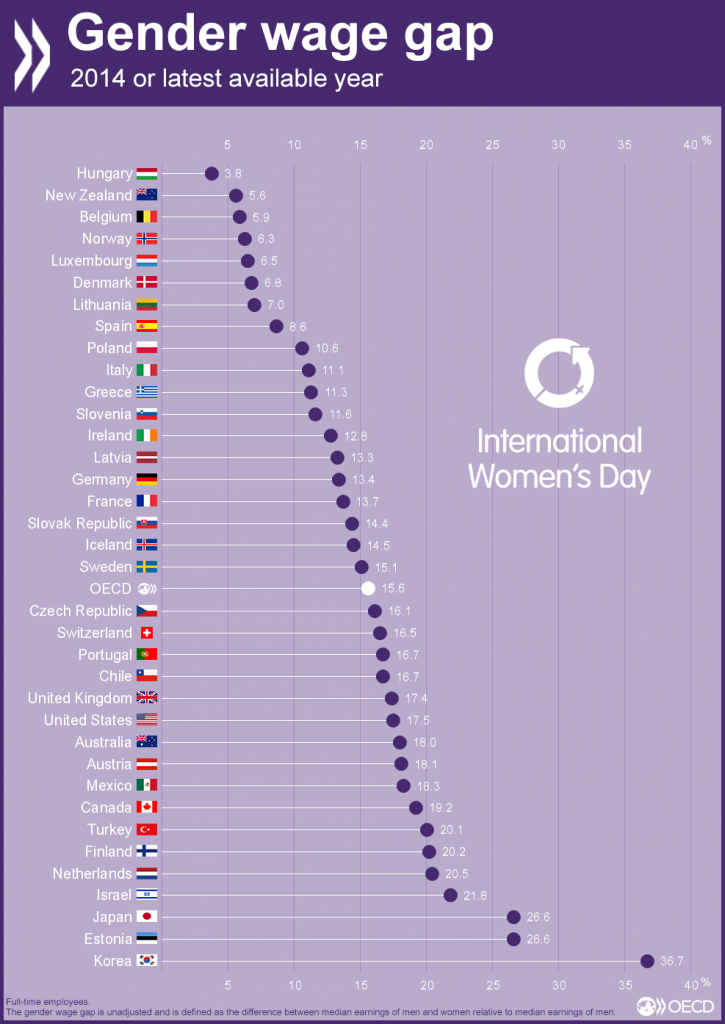

Financial considerations are powerful factors in making leave decisions. Women still make about 15 per cent less than men, on average in OECD countries. So economically speaking it often simply makes more sense for fathers to continue working, especially if parental leave is paid at much lower rates than previous earnings or not paid at all. The period around childbirth is often a time of considerable stress on household budgets. Many families may feel that they cannot make that sacrifice. Arguably, neither Prince William nor Mark Zuckerberg had to lose sleep over making serious dents in family income when deciding to spend their time cuddling and changing diapers for a while.

Figure 2: Gender wage gap

Source: OECD

Not surprisingly, research suggests that fathers’ use of parental leave is highest when leave is not just paid but well paid – perhaps around half or more of previous earnings. The father quotas in Iceland and Sweden are relatively well paid at over 60 per cent of last earnings. Similarly, a 2007 policy reform in Germany introduced well-paid bonus months for partners; as a result the share of children whose father took leave increased by over 50 per cent in Germany between 2008 and 2013, reaching 32 per cent.

But gender norms and cultural traditions still present serious obstacles to fathers taking leave. A 2013 survey by the Korean trade unions asked Korean fathers why they decided not to take leave; it showed that more than half were worried about the negative prejudices that they would be exposed to. In France, where men account for only 4 per cent of parents claiming parental leave benefits, 46 per cent of the fathers who did not take their full leave entitlement said that they were simply “not interested”. And in all but 6 OECD countries, at least 50 per cent of people surveyed by the International Social Survey Programme believe that paid leave should be taken ‘entirely’ or ‘mostly’ by the mother; and in the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic and Turkey a whopping 80 per cent of respondents agreed with this statement.

Finally, employers’ opinions and the environment in the company obviously play a crucial role. Some employers may regard a father taking long leave as not being committed to his job, leading fathers contemplating a longer break to fear for their career and promotion prospects. In Japan and Korea, fathers taking paid parental leave are concerned this would have negative effects on their career and their relationship with colleagues. Such workplace attitudes may be less pronounced in many other OECD countries, but even in Sweden, working in a small workplace or in one with a long-hours culture can keep fathers from using parental leave.

Public policy can provide the best conditions to enable fathers to spend more time with their children. But change needs to come both from employers and fathers themselves if we want to succeed in a better sharing of paid and unpaid work between men and women. This is not only about promoting gender equality at work and at home; it is also about improving the quality of life – for men, women and children.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: father and daughter, public domain.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1M4aW5F

_________________________________

Monika Queisser – OECD

Monika Queisser – OECD

Monika Queisser is Head of Social Policy Division at OECD.

Willem Adema – OECD

Willem Adema – OECD

Willem Adema is Senior Economist in the OECD Social Policy Division.

Chris Clarke – OECD

Chris Clarke – OECD

Chris Clarke is Junior Economist in the OECD Social Policy Division.