Three state elections were held in Germany on 13 March, with the contests being viewed as a key test of support for Angela Merkel’s government in light of her handling of the ongoing migration crisis in Europe. Assessing the results, Ed Turner writes that the elections demonstrated substantial discontent among German voters, with the Alternative for Germany securing large vote shares in all three states.

Three state elections were held in Germany on 13 March, with the contests being viewed as a key test of support for Angela Merkel’s government in light of her handling of the ongoing migration crisis in Europe. Assessing the results, Ed Turner writes that the elections demonstrated substantial discontent among German voters, with the Alternative for Germany securing large vote shares in all three states.

State elections in Germany matter – they elect those who govern each of the 16 states (or Länder), which is significant in its own terms as the states determine policy in important areas (first and foremost, education). They decide the composition of the country’s second chamber, the Bundesrat, which has a veto on any legislation affecting the states (between a third and half of all laws), and where a hostile majority can bring government to a standstill (as both Helmut Kohl and Gerhard Schröder found out through bitter experience).

They are often the first step on the road to national importance for new parties (state governments being a critical testing ground for new coalition possibilities – with state-level alliances between Social Democrats (SPD) and Greens paving the way for that coalition nationally, and coalitions between Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and Greens also being closely observed for possible replication). And of course, they are an important signal of the political mood of voters between national elections (with academic studies finding that national and regional issues both play into state-level voting behaviour).

At times, this can have far-reaching consequences – the Social Democrats’ shock defeat in Hesse in 1999 led to a significant shift in policy and the scaling back of proposals to extend dual nationality; the same party’s defeat in 2005 in North-Rhine Westphalia prompted Chancellor Gerhard Schröder to call new federal elections, which saw Angela Merkel elected to power. Given the controversy around Chancellor Merkel’s handling of the refugee crisis, the three elections on 13 March were therefore closely watched around the country and beyond – would voters take the opportunity to give Merkel a bashing? In particular, there was much interest in how the right-populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) would perform. With characteristic German efficiency, results are collated quickly and excellent analysis is provided by Intratest Dimap, from whom data cited here comes.

The results

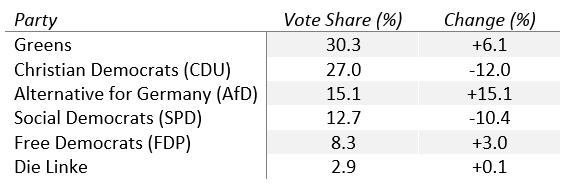

In the prosperous south western state of Baden-Württemberg, the Greens under their popular Minister President Winfried Kretschmann topped the poll (for the first time in any state election in the country’s history) with 30.3 per cent (+6.1 per cent), and the Christian Democrats falling to 27 per cent (-12.0 per cent), a historic low. Remarkably, 75 per cent of voters stated they would prefer Kretschmann as Minister President, compared to just 16 per cent to the other viable contender, the CDU’s Guido Wolf. However, the Greens’ coalition partner, the SPD, also suffered a hammer blow, falling by 10.4 per cent to 12.7 per cent, meaning the existing Green-SPD coalition no longer enjoys a majority. The AfD scored 15.1 per cent, becoming the third-placed party.

Table 1: Results of the 13 March election in Baden-Württemberg

Source: Intratest Dimap

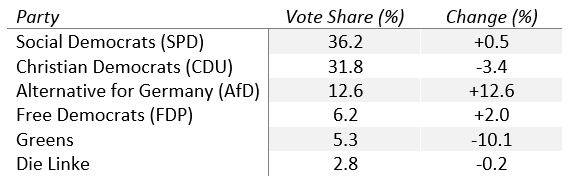

In the attractive western state of Rhineland-Palatinate (home of much of Germany’s winegrowing industry), the SPD’s Minister President Malu Dreyer also scored well – the SPD topped the poll with 36.2 per cent (+0.5 per cent), while the CDU (under former “wine queen” Julia Klöckner) fell 3.4 per cent to 31.8 per cent. Dreyer was the favoured choice of 54 per cent of voters for Minister President, compared to 34 per cent for Klöckner. Here, the SPD’s coalition partner, the Greens, had a disastrous result, falling 10.1 per cent to just 5.3 per cent (so that the coalition will no longer have a majority), and the AfD got 12.6 per cent, again netting them third place.

Table 2: Results of the 13 March election in Rhineland-Palatinate

Source: Intratest Dimap

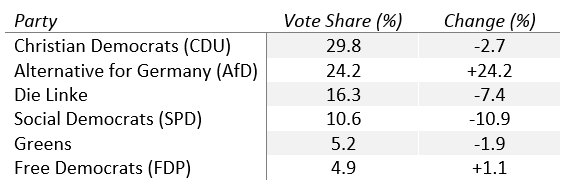

In Saxony-Anhalt, an eastern Land struggling with substantial unemployment, the headline was the success of the AfD, which scored 24.3 per cent, not far behind the election winner, the ruling CDU (29.8 per cent), with the SPD and also Die Linke (the Left Party), traditionally strong in the east, also losing ground. Here, too, the ruling coalition of CDU and SPD will no longer command a majority.

Table 3: Results of the 13 March election in Saxony-Anhalt

Source: Intratest Dimap

What, then, do these elections tell us? Here are some initial pointers. First, a significant section of the electorate is angry, notably (if not exclusively) about government policy on migration, with the elections generating one of the best results ever for a party to the right of the CDU (only the 19.4 per cent for a populist authoritarian organisation in Hamburg in 2001, the far right Republikaner in Baden-Württemberg in 1992 with 10.9 per cent, and the far right DVU in Saxony-Anhalt with 12.9 per cent in 1998, really compare in recent times). Undoubtedly, this will trouble many in the CDU and beyond, and voices criticising Chancellor Merkel’s approach to the issue in her own party, and particularly its Bavarian sister organisation the CSU, will feel emboldened. It is worth noting, though, that in all three Länder, the greatest number of AfD voters were previous non-voters, rather than disgruntled former Christian Democrats.

Second, state parliamentarians in the CDU who tried to distance themselves from Chancellor Merkel on her refugee policy got nowhere. All three state CDU leaders attempted an element of distancing – the most cautious of these, Reiner Haseloff in Saxony-Anhalt, got the least bad result, and the voters considered Julia Klöckner and Guido Wolf’s criticisms of Merkel were unfair, and even motivated by a longing for power, rather than concern about the substantive issue. And Merkel’s star continues to shine even beyond the refugee issue – 72 per cent of CDU voters in Saxony-Anhalt stated that “Angela Merkel is the most important reason to vote for the CDU”. The Green success story of the night, Kretschmann, was occasionally mocked as being a “stalker” of Chancellor Merkel, so supportive was he of her policy towards refugees, and Merkel’s approach also received support from the SPD’s victor in Rhineland Palatinate, Malu Dreyer.

Third, these elections are highly unlikely to see a change in the leadership of any of the three states: all three Minister Presidents’ parties topped the polls (pointing to some incumbency advantage) and the balance of power in the Bundesrat will barely be affected. There will, however, be a need to test out new coalitions: in Saxony-Anhalt, the most likely one is between the CDU, SPD and Greens; in Baden-Württemberg, the Greens and SPD are likely to try to bring the liberal FDP on board (into a so-called “traffic light coalition”); and that is also a possible model for Rhineland-Palatinate. Social Democrats, in their more optimistic moments, might see the “traffic light” option as a possible way back to the chancellorship nationally.

Fourth, there might be an incumbency bonus for Minister Presidents, but being a junior coalition partner is most definitely a poisoned chalice, with each of these seeing a collapse in its electoral support (reminiscent of the British Liberal Democrats at the 2015 general election). This will be deeply worrying for Germany’s Social Democrats, struggling to achieve any sort of profile as Chancellor Merkel’s junior partner, and now looking a very long way indeed from power.

Indeed, one final lesson of these results, and of recent decades in German politics, is that when there is a “grand coalition” between the main party of the centre-right (CDU/CSU) and centre-left (SPD), discontent is likely to emerge on the left or, as happened in Sunday’s regional elections, on the right. Yet when the recipient of the support of disgruntled electors (in this case, the AfD) is not considered a viable coalition partner, coalitions of major parties, straddling the centre ground, become ever more likely – in turn, confirming the views of voters that mainstream parties are all the same, and driving more of them towards populist alternatives (a turn of events that eventually led right-wing parties to power in the Netherlands and Austria). We might call this the “vicious circle of grand coalition politics”, and it is hard to see Germany escaping from it any time soon.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Metropolico.org (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1LlVt6f

_________________________________

Ed Turner – Aston University

Ed Turner – Aston University

Ed Turner is Senior Lecturer and Head of Politics and International Relations at Aston University, based in the Aston Centre for Europe. He has written widely on German party politics and federalism.

The rise of the Afd can be credited to the governments refusal to listen to the concerns of the people. In fact, not only did the government ignore the people’s concerns, but it went on a campaign to discredit the people’s fears by having the “lying press” label the people with bully-like names such as “nazi’s” or “Islamaphobes” or “xenophobes” (not a good way to win over public opinion). Additionally, the government and the “lying press” conspired in a cover-up to hide the events in Cologne on New Years Eve, along with cover-up other crimes committed by migrants. But because of the name-calling and cover-ups, the focus was on the lying government, and less so on the substance of the policies. If the government had been honest and open, then the merit (or lack of merit) of the policies could have/should have been debated (instead of their being personal attacks).

Historically, German leaders’ horrible policies have led to disaster within Germany (both Kaiser and Chancellors). So here is one more for the history books.

This is not a “migration crisis”, it is a crisis for the citizens of Europe who never asked for hundreds of thousands of migrants from across the world to be imposed on them and their societies.

Hopefully, what has happened in Germany will be duplicated across Europe and parties who will address this will be elected and the ruling parties who encouraged these migrants to come to Europe will be thrown out of office

The people were never asked because Frau Merkel unilaterally decided to impose her will upon German citizens and to the rest of Europe. Although she alone had no legal authority to “open the borders” to any alleged “refugee” (which includes legitimate refugees, economic migrants, invaders, criminals, etc…), she somehow did, and the other European leaders sat there like sheep and did nothing about it (except Hungary, and now the Balkans). But why should Frau Merkel have listened to the people, after all, both Bono from U2 and the Hollywood Rasputin (and his wife Amal) are giving Merkel praise for her allowing them to influence German policy. The people are a mere afterthought; hence, the election results were not good for the CDU.