How successful has the West been in implementing its state-building process in Kosovo? Andrea Lorenzo Capussela writes that despite extensive support from the West, Kosovo still ranks poorly on a number of key indicators and has a persistent problem with organised crime and corruption. He argues that if the West is unable or unwilling to confront Kosovo’s leadership and expose them to political and economic competition, as it pledged to do when it supported the territory’s independence, it should scale down its involvement to the level of other countries in the region.

How successful has the West been in implementing its state-building process in Kosovo? Andrea Lorenzo Capussela writes that despite extensive support from the West, Kosovo still ranks poorly on a number of key indicators and has a persistent problem with organised crime and corruption. He argues that if the West is unable or unwilling to confront Kosovo’s leadership and expose them to political and economic competition, as it pledged to do when it supported the territory’s independence, it should scale down its involvement to the level of other countries in the region.

Kosovo was the theatre of the most ambitious, intensive, and expensive state-building intervention ever launched. It was a comparatively easy case for at least three reasons: because the separation from Serbia after the 1999 NATO intervention had removed the main proximate cause of instability, i.e. the tensions between the Albanian majority and the Serb minority; because what the population asked for – liberal democracy, a functioning market economy, and Euro-Atlantic integration – was what the West offered to do, and spent liberally for; and because no other power either threatened Kosovo or contested the West’s influence.

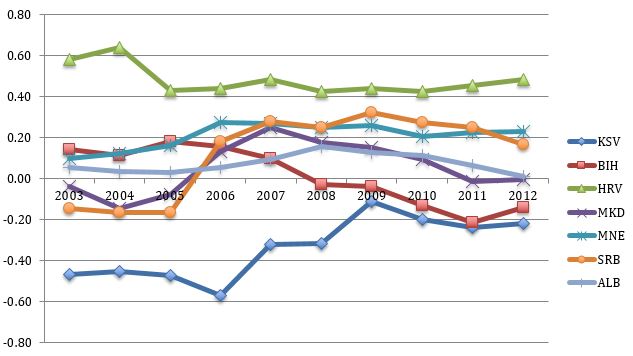

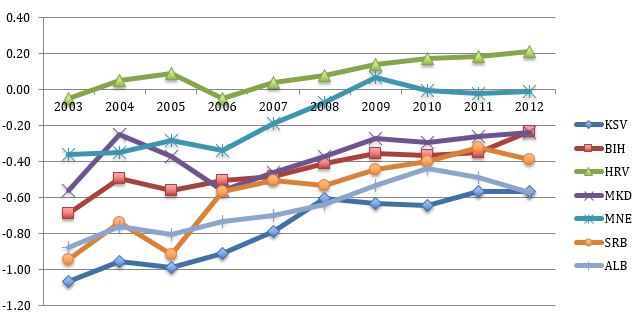

And yet, Kosovo’s political and economic institutions remain gravely inefficient, with the lowest scores in the region on a number of key indicators, as Figures 1 and 2 indicate. The charts are drawn from my book on Kosovo and cover the period 2003-2012 (i.e. the last half of the UN’s eight-year long administration and the subsequent four years of internationally supervised independence).

Figure 1: Voice and accountability indicators in the former Yugoslavia

Note: The abbreviations in the chart refer to Kosovo (KSV), Bosnia and Herzegovina (BIH), Croatia (HRV), Macedonia (MKD), Montenegro (MNE), Serbia (SRB) and Albania (ALB). Source: World Bank Institute (Worldwide Governance Indicators)

Figure 2: Rule of law indicators

Source: World Bank Institute (Worldwide Governance Indicators)

Indeed, according to a 2015 EU report, corruption is ‘omnipresent’, organised crime is equally widespread, and impunity systematic. Poverty, unemployment, and popular discontent are worryingly high. Relations between minorities and the 93 per cent Albanian majority remain difficult. And, since its independence, Freedom House qualifies Kosovo as a ‘semi-consolidated authoritarian regime’ – the only one in the Balkans.

The West’s delusion

During a recent stay in Kosovo, I had encounters with journalists and civil society, but also with a few opposition politicians, intellectuals, and foreign diplomats. These conversations left me with the impression that parts of the international community still nurture the hope that someday Kosovo’s political leaders will shed their predatory inclination and become genuine statesmen.

The idea was current among diplomats and international officials while I worked there, in 2008–11, and did influence their policy choices. In the years around Kosovo’s independence the belief might often have been sincere, if perhaps naïve. Subsequently it became the cover for a policy that viewed political stability as its highest priority, but which also had the effect of stabilising the governance system. And this belief is still expressed more frequently than might be expected, now that Kosovo’s problems seem no longer concealable.

Many of the actors that determine western policy on Kosovo believe that its leadership presides over, and benefits from, a governance system under which corruption and organised crime prosper. But they also expect, or proclaim the hope, that at least some of these elites will abandon these practices and devote their energies toward the democratic and economic development of the country. However these two convictions – that these actors are corrupt but sooner or later they will become statesmen – are, and have always been, inconsistent. As such, the West should either strengthen its level of intervention in Kosovo, to bring about a change in the governance system, or begin treating Kosovo as it treats the other countries of the region that aim to join the EU (Albania, Bosnia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia).

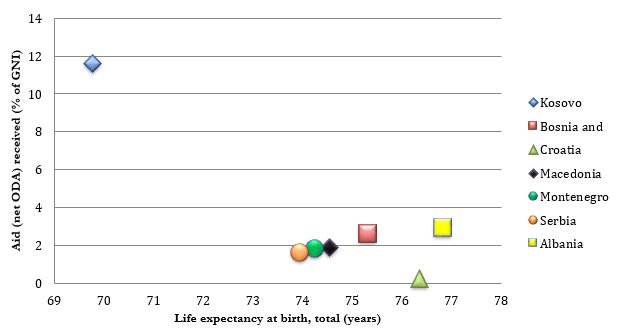

Although these other states have received a fraction of the attention and aid that the West has devoted to Kosovo, they have generally progressed at a faster pace in terms of efforts to strengthen democracy and the rule of law, as shown in the two figures above. Indeed, the correlation shown in Figure 3 suggests that the failure to establish efficient political and economic institutions in Kosovo has led much of the aid to be diverted or misallocated, with adverse effects on both governance and living standards. The long-standing western policy of supporting Kosovo financially and its leadership politically has damaged both the country’s and the West’s long-term interests – and might no longer even secure short-term stability, as Kosovo’s recent political crisis suggests.

Figure 3: Correlation between aid and life expectancy

Source: World Bank; 2008-2012

Misalignment between Washington and Europe

My book argues that among the causes of this policy is a fundamental misalignment between the interests and the influence of the United States, on the one hand, and those of the EU and its main member states, on the other. The Europeans have a clear interest in seeing Kosovo mature into a reasonably stable and prosperous democracy, but lack the necessary influence to facilitate its development, whereas Washington, which remains dominant in Kosovo, lacks the incentive to apply its influence to that end. A policy change along the lines I describe would require renewed negotiations between the US government and the Europeans.

Western diplomats and politicians tend to only link Kosovo’s leaders to corruption and organised crime in a generic or indirect fashion. Yet the intelligence reports that have been leaked since 2009, or summarised in official reports, cast some light on what western governments know about the situation on the ground. For instance, a 2010 Council of Europe report quotes two German intelligence analyses dating from 2005 and 2007, both in the public domain now, which describe much of the current leadership of three of the five main political parties in Kosovo as ‘key personalities of organised crime’. The ‘criminal boss’ whom these reports view as the ‘most dangerous’ has just been elected president of the republic, after having served as the political leader of Kosovo’s guerrillas in 1998–99, having founded and led Kosovo’s main political party, and having governed the country from 2007 until 2015.

Why Kosovo’s leadership will resist strengthening the rule of law

It would not be too unrealistic to assume that corruption and organised crime involve between twenty and eighty thousand people, or between about 1 and 5 per cent of the population (from those ‘key personalities of organised crime’, who are both politicians and businessmen, down to junior civil servants, shopkeepers, or the watchmen of the storage sites for narcotics or weapons). And it can safely be assumed that, were the law to be enforced rigorously upon this segment of the population, most of them would face stiff prison sentences and restitution claims (for the current governance system has existed since about 1999, and both corruption and organised crime are professional, serial crimes: those who engage in them tend to do so repeatedly).

In such circumstances, establishing the rule of law is impossible if the power of Kosovo’s leaders remains effectively unchallenged. A model built by Karla Hoff and Joseph Stiglitz, which rests on broadly similar assumptions, helps to demonstrate why. In short, establishing the rule of law implies high risks for the wealth and personal freedom of Kosovo’s elite and its operatives, clients, and business partners. Only a wide amnesty, formal or informal, would avoid such risks; but unless the amnesty is part of a power-transfer agreement imposed by forces with enough power to challenge Kosovo’s leadership, any transfer of power would be superficial and actors would accept the amnesty only to secure their past gains and continue their predatory practices.

The West’s belief that such actors will develop into genuine political statesmen assumes that they will eventually need the rule of law to secure their gains. But, as Branko Milanovic has previously written with reference to Russia’s privatisation programme, these actors may never need the rule of law in their own state, if their ill-gained wealth can be safely placed abroad. Conceivably, however, the argument could be turned on its head: for instance, if the West were to offer certain actors secure retirement abroad in exchange for ceding power. But this is only a solution only for those in the upper echelons of power: those involved at a lower level (between 1 and 5 per cent of the population, in our assumption) will remain in Kosovo and they will have no reason to cede power. Indeed, they would have a stake in replacing the higher ranking individuals, keeping the political system closed, and continuing as before. As such, this solution would merely result in a reshuffle at the top rather than a genuine shift toward securing the rule of law.

The need for fresh challengers within Kosovo

Real change is only possible in Kosovo if the current leadership’s political, economic, and military power is credibly challenged by other forces: by a broad-based and pluralist alternative political coalition, ideally, or else by a popular revolt or the political and military power of the West. But none of these forces have yet emerged, or shown the necessary determination to effect change within Kosovo. There is no alternative pluralist coalition to unseat the current leadership and while there have been signs in recent months of possible unrest, this is (thankfully) a long way short of a revolution.

Since 1999 the West has preferred to appease, rather than confront, Kosovo’s leadership. This policy and the absence of a credible political alternative are linked, of course, for the West’s explicit and implicit support for the existing leadership has helped it to keep the political system closed. For example, the arrest of a handful of opposition MPs drew hardly any criticism from the West, which predictably encouraged further arrests (at one point almost half of the parliamentary opposition was either in jail or under house arrest).

The West should either intervene usefully or leave

Hence the two alternatives I mentioned above. Either the West acts on the mandate it gave itself in 1999, and reiterated in 2008, to establish democracy and the rule of law, or it should abstain from interfering in Kosovo’s political evolution. This would imply reducing aid to the average level across the region (as Figure 3 indicates in 2009-12, Kosovo received six times that, relative to the size of national income), and withdrawing all international missions other than those found elsewhere.

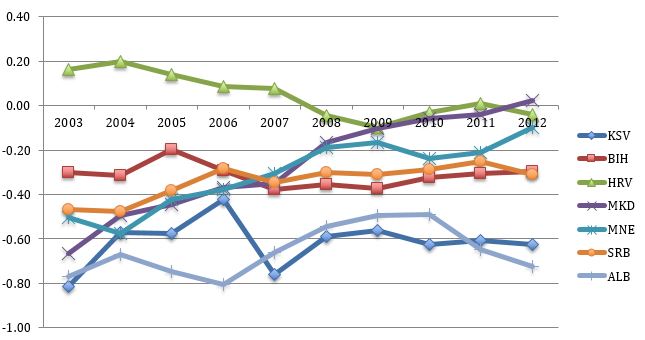

In the next few weeks, for example, the EU will have to decide whether to extend or terminate the mandate of its rule-of-law mission, named ‘Eulex’. The most innovative and important part of its mandate was to repress political corruption and organised crime. At its peak, the mission employed three times as many officials as the eleven other extant (CSDP) missions combined. Yet the available indicators – summarised by Figure 4 – suggest that in Kosovo corruption has marginally risen, not declined, between 2008, when the mission was deployed, and 2012, when its powers and staff began a steep reduction.

Figure 4: Control of corruption

Source: World Bank (Worldwide Governance Indicators)

Maintaining this remarkably ineffective mission – with an overall cost that far exceeds €1bn: more than EU aid to Ukraine, for example, in per-capita and per-year terms – is highly likely to continue to damage both Kosovo’s and the EU’s interests. Indeed, the same EU report that judged that corruption is ‘omnipresent’ in Kosovo argued, correctly, that the mission should be either reformed or withdrawn. But reforming it in such a way that it may plausibly begin pursuing its original mandate seems a daunting task, for the mission would have to end the mutual non-aggression pact it struck with Kosovo’s leadership, mirroring the West’s preference for short-term stability over governance reform, then regain the executive judicial and police powers it has ceded to Kosovo’s institutions since 2012, and considerably increase, and carefully vet, its staff.

It is true that the EU mission has just launched a corruption investigation involving one of those ‘key personalities of organised crime’. But the circumstances of the case and past practice suggest caution before concluding that the mission has adopted a more determined crime-repression policy (for instance, only one of the eight well-documented cases discussed here has been pursued; yet all concern equally or more prominent suspects, and far greater economic interests: in one case alone, that of a highway, the amount of public money lost can be estimated at €400 million, or 10 per cent of the then GDP).

So the case of this mission nonetheless suggests that the West is unlikely to be willing, or able, to change its policy, strengthen its intervention, confront Kosovo’s leadership, undermine the unhealthy foundations of its power, and expose it to political competition (while favouring, to the extent possible, the emergence of a broad-based alternative political coalition, whose pluralist character may ensure that the political system remains open). This would be regrettable, as the international intervention in Kosovo was well designed and could have opened promising developments for the practice of state and peace-building. Indeed, as I suggested at the outset, it probably was the ideal experiment for a new approach to state-building. But if the implementation of those good ideas has deformed them to the point that the state-building intervention is beyond reform, as seems to be the case, the experiment should be brought to an end, in both Kosovo’s and Europe’s interests.

Left to its domestic dynamics, Kosovo’s evolution will remain uncertain, between the consolidation of an authoritarian regime, which might perhaps ensure greater order than the current hybrid regime does, its gradual opening, or a more abrupt or disorderly transition (Montenegro and more recently Macedonia seem to be moving in that direction). Nothing guarantees that Kosovo’s evolution will not take an undesirable trajectory: but at least the West will not continue acting as an obstacle to positive change.

Protecting Kosovo’s minorities

Western powers cannot withdraw entirely, however, at least in the medium term. In the blueprint for Kosovo’s independence, the so-called ‘Ahtisaari plan’, the West and the new state promised to the country’s minorities a very high degree of protection, which was duly translated into laws and constitutional provisions. Yet, as the rule of law is very weak these protections remain largely on paper.

If it judges that it cannot strengthen the rule of law – and therefore withdraws from Kosovo, as I suggest – the West should nonetheless guarantee at least a basic degree of security to Kosovo’s minorities, which remain marginalised and whose members appear to be more vulnerable than the average citizen. Suffice it to say that a report by the US State Department on respect for human rights counted in 2015 ‘more than 254 incidents’ involving violence against members of the Serb minority (whose size may be estimated at 80,000, or 4.5 per cent of the population).

And an illustration – anecdotal, certainly, but indicative – of the conditions of the Roma minority is the death, a few months ago, of a small child: killed by a dog, which probably saw him as a competitor in the search for edible remains in a rubbish dump on the outskirts of Kosovo’s capital. So the remaining international presence should be aimed only at the protection of Kosovo’s minorities (including, I suppose, the Albanian minority in Serb-dominated North Kosovo). Integration and social cohesion will come together with the rule of law, an open democratic system, and higher incomes, if Kosovo will evolve in this direction.

The advantages of government by discussion

This reading of the situation in Kosovo may well appear pessimistic and overly simplistic. In particular, the West’s withdrawal from Kosovo will require a far more thoughtful, sophisticated policy than can be articulate here. But it is important to challenge the widespread assumption that Kosovo’s leadership can be encouraged to develop along the lines the West expects: the only function of this belief is to delay the moment at which western actors will have to explain to their domestic constituencies why the state-building process established in Kosovo has failed, and why we now need to facilitate an open discussion on what to do next.

Had it been subjected to a public and reasoned debate before Europe’s electorates, the policy to support a predatory, unaccountable, and often irresponsible leadership in Kosovo would most probably have been discontinued long ago. This suggests that greater democratic accountability might benefit not just Kosovo, but also the conduct of EU foreign policy. Western actors might also wish to study the Kosovo experiment carefully, for the lessons that can be drawn from it could prove useful in the cases now appearing over the horizon – such as Ukraine and potentially Libya and Syria – though none of these cases presents conditions as favourable as Kosovo did.

Kosovo’s citizens should now choose for themselves whether they prefer to cement the current ‘semi-consolidated authoritarian regime’ to establish a greater level of order throughout the country, or whether they prefer to open up the political system and thereby have both order and democracy. The sooner this choice is laid out in front of them, the better.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1W8fmBb

_________________________________

Andrea Lorenzo Capussela

Andrea Lorenzo Capussela

Andrea Lorenzo Capussela holds a PhD on competition policy. After a few years in the private sector, he served as the head of the economics unit of Kosovo’s international supervisor, the International Civilian Office, in 2008–11, and, in 2011–13, as the adviser to Moldova’s economy minister and deputy prime minister, on behalf of the EU. He is the author of State-Building in Kosovo: Democracy, EU Interests and US Influence in the Balkans (London: I.B. Tauris, 2015), and, together with Vito Intini, he is writing a book on Italy’s political economy for Oxford University Press.