Spain held a general election on 26 June, just over six months after the last election in December failed to produce a governing coalition. The vote saw Mariano Rajoy’s People’s Party gain the largest share of seats, but not enough for a majority in parliament. Anwen Elias writes that the result demonstrated the resilience of the country’s two mainstream parties in responding to the challenge from Podemos and Ciudadanos, but that the next government will still need to be based on untried coalition partnerships which will require a high level of compromise.

Spain held a general election on 26 June, just over six months after the last election in December failed to produce a governing coalition. The vote saw Mariano Rajoy’s People’s Party gain the largest share of seats, but not enough for a majority in parliament. Anwen Elias writes that the result demonstrated the resilience of the country’s two mainstream parties in responding to the challenge from Podemos and Ciudadanos, but that the next government will still need to be based on untried coalition partnerships which will require a high level of compromise.

There has been much talk in Spain recently of a fundamental transformation of the country’s politics. The two-party system that has characterised Spanish politics in the post-Franco period appears to be giving way to a new multi-party politics. Evidence for this is found in the fact that many established political parties have lost substantial electoral support to new and previously marginal political actors advocating a radically different way of doing and talking about politics.

The extent of this electoral shift is reflected in the declining appeal of Spain’s two largest parties in recent years. The combined vote-share of the left-wing Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) and the right-wing Partido Popular (PP) increased gradually throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, and reached a high of 83.81% (and 323 parliamentary seats out of 350) in the 2008 general election.

By the December 2015 general election, this had fallen to an all-time low of 50.71% (213 out of 350 seats). This was largely as a consequence of the spectacular electoral growth of two new parties: Podemos (winning 12.67% of the vote and 42 seats) and Ciudadanos (13.93% and 40 seats). This new balance of electoral forces, and their divergent (and ultimately irreconcilable) political priorities, contributed to the failure of government formation negotiations six months ago and paved the way for new elections on 26 June.

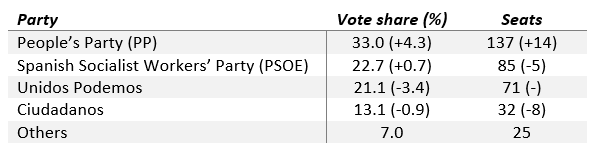

Table: Result of the 2016 Spanish general election

Note: Vote share rounded to one decimal place. Changes from 2015 are shown in brackets. For more information on the parties see: People’s Party (PP – Partido Popular), Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE – Partido Socialista Obrero Español), Unidos Podemos, Ciudadanos (C’s).

What does this latest electoral contest tell us about Spain’s transition to multi-party politics? Firstly, there is evidence of the resilience of Spain’s historically dominant political parties. The combined vote-share of the PP and the PSOE recovered slightly to 55.69%, mainly as a result of the former’s success in clawing back some of the support lost six months previously. The PP thus remains the largest party in the Spanish parliament by some distance, with the PSOE in second place having (only just) fended off the left-wing challenge from the Unidos-Podemos alliance (an alliance between Podemos and two other parties – United Left and Equo). It is clear that the ‘old’ is not about to give way to the ‘new’ without a fight.

Secondly, yesterday’s election represents an important set-back for the new political challengers’ aspirations for political transformation. Ciudadanos’ centrist strategy – presenting itself as a ‘pivot’ between (and potential coalition partner for) the PP and PSOE – lost, rather than won, the party votes and seats (from 13.93% and 40 seats in 2015, to 13.05% and 32 seats in 2016). For Podemos, the new electoral alliance with the United Left (as Unidos Podemos) polled fewer votes than did both organisations separately in 2015; it failed to replace PSOE as the second largest political force, thus making it impossible for it to lead the formation of a new left-wing coalition in Madrid. Both parties thus failed to meet their strategic goals, and with it their ambition to completely transform Spanish party politics.

Thirdly, Spain’s politics has always been more plural than the ‘two-party system’ characterisation suggests. There has always been a broader range of political voices represented in the Spanish parliament, reflecting ideological positions ranging from socialism to liberalism, republicanism to monarchism, and independence to centralisation. The electoral fortunes of these different forces have waxed and waned over time, and numerically these parties have always been too small to challenge the PSOE and PP for central government office.

But on several occasions they have been important in granting the latter governing majorities in Madrid. And whilst these smaller parties are also being challenged by new electoral rivals, there is as yet no evidence that they are being squeezed out of political competition. This is the case, for example, for nationalist parties in the Basque Country and Catalonia: in yesterday’s contest, these parties almost all held on to the votes and seats they won six months previously. Like their established state-wide counterparts, these parties seem to be adapting, rather than giving way, to new dynamics of electoral competition. The result is an even more plural and complex politics than previously existed, rather than a qualitatively different kind of politics.

So Spain’s party politics has never been just about two parties. Nor are we seeing the inevitable end of the old and the straightforward consolidation of the new. At the same time, however, yesterday’s general election may still require decisions about government formation that are unprecedented in the Spanish context. The parliamentary arithmetic means that a country that has long been accustomed to single party governments, and the routine alteration of the PP and PSOE in office, may for the first time be on the verge of untried coalition partnerships. The coming weeks will see all these options explored. A compromise solution – a fundamental requirement of multi-party politics – will need to be found if Spain is to avoid going to the polls again.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: Mariano Rajoy (public domain).

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/294HbtX

_________________________________

Anwen Elias – Aberystwyth University

Anwen Elias – Aberystwyth University

Anwen Elias is Reader in Comparative Politics at Aberystwyth University.