We are now in the final weeks of campaigning before Italy’s constitutional referendum on 4 December. As part of our coverage of the referendum, Mattia Guidi makes the case for why Italians should support the proposed reform. He argues that much of the criticism of the reform is unfounded and that it would ultimately bring Italy closer to the parliamentary systems used in other European countries.

We are now in the final weeks of campaigning before Italy’s constitutional referendum on 4 December. As part of our coverage of the referendum, Mattia Guidi makes the case for why Italians should support the proposed reform. He argues that much of the criticism of the reform is unfounded and that it would ultimately bring Italy closer to the parliamentary systems used in other European countries.

Interested in other points of view? Check out EUROPP’s full coverage of Italy’s constitutional referendum.

The referendum on the constitutional reform approved last April by the Italian parliament, to be held on 4 December, is polarising Italy’s party system and Italian society like few other issues have ever done before. Most political parties, on the left and on the right, are against the referendum. Even within the party that more than any other has contributed to the reform, the Democratic Party, there are important groups that are campaigning for a no vote. If the referendum had to be decided only on the basis of what parties suggest, the no vote should obtain a landslide victory.

For the time being, the situation appears more balanced: a slight majority (around 52-53%) of those who intend to vote are apparently willing to reject the reform, but the final result is still uncertain. In this piece, I intend to briefly summarise the content of the reform and then discuss some of the most common criticisms. My aim to is to show that the reform, despite its inevitable compromises, is a step forward because it would bring Italy closer to most parliamentary systems used in other countries without endangering the democratic nature of our Constitution.

What the reform contains and why criticism is wide of the mark

The content of the reform can be summarised in a few points:

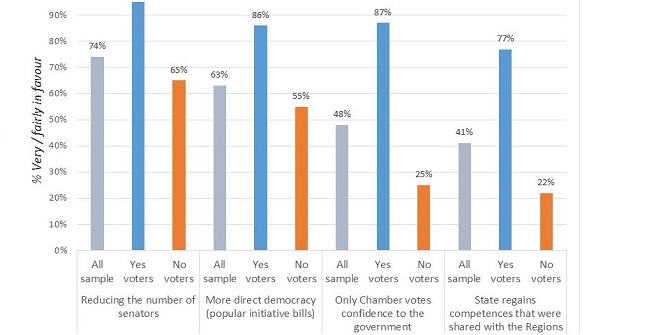

- The unique form of bicameralism used in Italy, with two chambers that are both directly elected, have to pass motions of confidence for the government to enter into office, and must agree on every piece of legislation, will be reformed. The lower chamber remains directly elected and keeps a ‘confidence relationship’ with the executive. The Senate becomes a chamber composed of members of regional assemblies and mayors, which will not vote on motions of confidence and has significantly reduced powers in passing legislation.

- The government will be given the capacity to ask the lower chamber to examine draft bills in a relatively short period of time (85 days). However, at the same time, the government’s power to pass decree-laws will be constrained.

- Instruments of direct democracy (referendums and popular legislative initiative) will be strengthened: if referendums to abrogate laws are supported by more than 800,000 voters, the quorum for their validity will be reduced to 50%+1 of the voters at previous general elections; referendums to pass laws will become possible; and the discussion of bills proposed by the people will become mandatory for the parliament.

- A number of competences which had been devolved to regions in 2001 are set to be returned to the state.

Critiques of the reforms come in various shapes and sizes. For instance, many opponents argue that Italy’s current form of bicameralism is necessary to maintain a system of “checks and balances”: if the reform passes, the government risks becoming too powerful. This criticism ignores that Italy is the only system in the world in which both chambers can carry out votes of confidence in the government and must agree on every bill. The reform would bring the Italian system closer to other bicameral systems, in which only the lower chamber retains a confidence relationship with the government, and the other chamber (almost everywhere indirectly elected, like the reformed Italian Senate) has more limited legislative powers.

Another common criticism concerns the nature of the new differentiated procedures for passing bills. Opponents of the reform criticise the complexity of the article describing these procedures. Obviously, stating that both chambers must agree on every bill is quicker than specifying differentiated procedures. But this argument clearly disregards the fact that differentiated legislative powers require constitutions to specify precisely which procedures are applied for specific types of laws, and how the procedures themselves work (for a comparative assessment, see, for example, Articles 76, 77 and 78 of the German Constitution).

It is also argued that the new legislative process would be less efficient and would generate confusion over the two chambers’ competences. Yet the reform would give the lower chamber the last word on almost every bill. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that the Senate would exercise its power to examine bills on every new piece of legislation. It would most likely focus on the limited number of bills for which it has full competence and on bills whose impact is crucial for the regions.

Regarding the government’s power to ask the lower chamber for a ‘fast track’ procedure for important bills, this is often criticised as an intolerable increase of the executive’s power. But looking closely at the text, we can see that the government would just have the power to ask the chamber to vote on a bill within 70 days, which can be extended to 85.

A few things must be noted here. First, 85 days would be almost three months to examine a bill. Second, the lower house can refuse to comply with the government’s request. And third, the parliament is free to amend the bill as it wishes (it is not a vote on a text drafted by the government, as in the case of France’s vote bloqué). All in all, it would be nothing more that the government declaring a bill important and asking the parliament to examine it relatively quickly. This is not exactly the death of parliamentary democracy. Moreover, the government’s power to pass decree-laws would also be reduced at the same time.

A more formal argument against the reform regards the majority that supported it in parliament. It is often argued that this majority was ‘slim’ and therefore inappropriate for a reform of this kind, which would require broader majorities. But is this a real point of concern? In the drafting of the reform all parties in parliament were involved (even the Five Star Movement which nevertheless refused to participate). In particular, Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and the Northern League significantly contributed (Forza Italia even voted for the reform at the first reading in the Senate). The majority in favour of the reform, in both chambers, has never gone below 56% of members – and let us remember here that, in the Senate, Renzi’s Democratic Party has only 33% of the seats.

The Constitution itself allows constitutional amendments to be adopted by an absolute majority of members (instead of two thirds) of each chamber, making it possible to hold a referendum in that case (which is exactly the present scenario). In a fragmented and polarised parliament like ours, these majorities are not easily achievable, and will be even more difficult to reach in the future. Passing the reform has required long negotiations and a process that has lasted almost two years (let alone the fact that most of these modifications have been discussed, and unsuccessfully attempted, for decades). Presenting the reform as a take-it-or-leave-it package that has been passed thanks to party discipline is greatly misleading. There has obviously been discipline in the parties involved, but this has been possible because many aspects of the reform have been amended during the process. This is evident if we simply look at the modifications introduced in the constitutional reform process. Ultimately, parliament has worked a great deal on the text that was agreed.

Great emphasis is also placed by the no campaign on the electoral system, which is considered too rigid and likely to transform electoral minorities into artificial majorities in parliament. Part of the criticism of the electoral law is well motivated. However, the electoral law is not part of the reform. It is an ordinary law, which can be modified by the parliament at any time with no special procedures, and which can also be partly cancelled through referendum. On top of that, the Constitutional Court will examine the new electoral system next January, and it will rule on its compliance with the Constitution.

What is more, the reform that opponents reject would allow one fifth of MPs to ask for a preventive judgment from the Constitutional Court on every new electoral law (and, exceptionally, on the current electoral law as well). Last but not least, there is an explicit commitment of the Democratic Party to change the electoral system. Presenting the electoral system as a ‘building block’ of the Constitutional reform is simply not correct, and it does not help in making a fair assessment of the reform. Rejecting a reform that has required many years, qualified majorities, and six readings to be passed because of disagreement on the content of the electoral law (which can be changed in a few weeks) is a decidedly odd approach to take.

Finally, and more generally, critics complain that the reform would create a kind of de facto presidential system. This is also an odd accusation given the reform mandates that the prime minister cannot appoint or dismiss ministers autonomously; the prime minister cannot even ask to dissolve the lower chamber; a vote of no confidence can be passed without requiring the chamber to propose a new prime minister (there is no constructive vote of no confidence); and the government’s only power vis-à-vis the lower chamber is that of being allowed to ask the lower chamber for a vote on a bill within three months. If these accusations were true, we would be obliged to say that countries like Spain, the UK, and Germany are already de facto presidential systems, since the prime ministers in these countries are already more powerful than what the Italian prime minister would be after the reform.

In conclusion, the reform has a significant positive contribution: it effectively differentiates (in composition and functions) between the two parliamentary chambers. This is a long awaited reform which was extremely hard to achieve − considering that directly elected senators have voted to suppress their own body − and would most likely not be achievable for a substantial period of time if the reform is rejected.

The reform ultimately makes the Italian institutional structure less eccentric and more similar to that of other parliamentary democracies, getting rid of an absurd bicameral system which neither contributes to the quality and speed of legislation nor to government stability. It is normal to have reservations over particular aspects of a package of reforms − when such a comprehensive reform is passed, with such a complex procedure and several compromises in parliament, inconsistencies are unavoidable − but the overall result is that we would get closer to more ‘normal’ parliamentary systems. If the reform is rejected, we remain outliers. This is why I believe we should approve it.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Palazzo Chigi (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2fV1id8

_________________________________

Mattia Guidi – LUISS University

Mattia Guidi – LUISS University

Mattia Guidi is a post-doctoral fellow at the Department of Political Science and at the School of Government of LUISS University, Rome. He works on EU institutions and politics, competition policy, and independent regulatory agencies.

Here is my blog of 2008 that clarifies very similar points on Italy’s Senate:

http://cep.rhul.ac.uk/cep-blog/2008/3/13/the-italian-senate-a-case-for-reform.html

Thank you Mattia for a useful summary of some of criticisms and counter-arguments. I have one question left regarding the changes to the powers of regions and the central government. Could you explain why this is necessary or even desirable? As a general rule, I believe Italy needs more decentralisation, not less.

In the 2001 reform, the number of competences devolved to the regions was huge. Even in policy areas like energy, infrastructures, ports and airports, regions had the competence to legislate while the state could only determine the general principles. This has led to an enormous conflict between state and regions, which have contested each others’ legislative acts. The Constitutional Court has had to resolve these conflicts, and it has been overloaded by them. So, the reform tries to reduce this conflict by taking several competences back to the state (which I think is fine, given that these are strategic national policies, in which the state must have a final say) and introducing a “supremacy clause” by which the national parliament can legislate in matters reserved to regions if this is necessary to preserve the unity of the country. Will it work? We don’t know to which extent the conflict will be reduced, but I’m pretty sure it will. And we must consider that this re-centralization is accompanied by a role for regional legislators in the national parliament, in the new Senate.

I regret that this article neglects to mention that the constitutional changes would reserve the right to cancel EU treaties to the Italian Senate, which is not (directly) elected to the Italian people, and all but surely make it at best far more difficult to renegotiate or cancel Italy’s participation in the increasingly controversial treaties related to the euro and migration. It is for Italians, and only Italians, to decide these matters, but in my estimation this aspect is highly important.

I couldn’t talk about every aspect of the reform. However, I fail to see how that would be a scandal. The Senate would be almost directly elected (because the regional councilors that would become senators would be indicated by the voters – so the Senate would have in general a proportional representation of the population), and that the whole parliament has a say on EU treaties’ reforms is really the minimum degree of democratic accountability that we can grant for such important supranational decisions.

International treaties would normally be approved by the lower chamber only. The reform recognized that EU treaties are different, and requires the Senate to be involved. The rationale is that EU treaties’ changes are equivalent to Constitutional changes – and I think that’s pretty accurate.

I had lunch a few days ago with an Italian friend of mine who does’t live there but was back home recently. He’s not political – but is truly Italian.

He made two points straight away which tell me the referendum will fail. First Renzi was never elected by the Italian people, making him an undemocratic leader who has never lead a national election. The last election in Italy according to my friend put Berlusconni in power, who then resigned and the President has been appointing ever since. Having never run a national campaign before Renzi perhaps fails to see he is regarded as illegitimate. And anything he wants, it therefore follows, is illegitimate. He should have held a national election first, gotten a mandate and then proposed changes to the constitution. Not this way around.

Second point of my friend: Italy has lots of problems. Changing the rules of how the senate / parliament works does not have any immediate affect on the number of garbage collectors on the street, pot holes filled, etc etc. A quote from this article, “the reform that opponents reject would allow one fifth of MPs to ask for a preventive judgment from the Constitutional Court” illustrates that point exactly. My friend’s point – fix Italy’s problems first – then the constitution, not the other way around. Italians are worried about their jobs, their retirements, out-of-control immigration and their ability to put food on the table. Tinkering like this is wasting precious time.

As my friend is from a generally liberal profession I suspect Italians generally feel as he do, even without the usual Northern League / 5Star protest. I prediect 60 / 40 for ‘No’. Polls haven’t been close this year yet – they aren’t going to start now!

Mattia,

The United States initially had the same system, wherein the Senators were chosen by parliaments (in this case the Parliament of each respective state), and it proved to be so unpopular – the senators were seen as being puppets of vested interests – that they amended the constitution to allow direct election of the senators. If you exclude the Bill of Rights, which was added 2 years after the Constitution was promulgated and whose amendments were an organic part of the process of writing the Constitution, the Constitution has been amended 17 times in the last 227 years, with 6 or seven of the amendments stemming from two short bursts immediately after the civil war and in the 1960s, and 2 amendments, banning and repermitting alcohol, cancelling each other out. 8 isolated unrelated amendments in 227 years, almost all of them clarifying trivial administrative procedures, should give you an idea of how rare it is for this to happen, and how unsatisfactory the previous arrangement must have been.

Given the Americans’ experience and how controversial the euro has become in Italy, and how many people blame the euro for a good part of Italy’s economic problems, I – as an outsider- ask myself whether Italians will be happy with this proposed new arrangement.