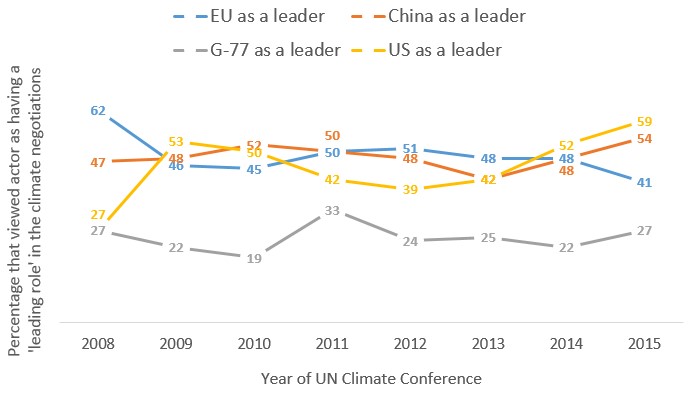

The EU has attempted to take a leading role in climate negotiations, but how effective has it been in shaping agreements? Charles F. Parker and Christer Karlsson present survey evidence from eight climate summits leading up to the Paris agreement in 2015. They highlight that although the EU’s perception of itself as a world leader was not shared to the same extent outside of the EU, it was still perceived to be one of the key leaders alongside China and the US.

On 12 December 2015, at the climate summit in Paris, 196 countries adopted a landmark climate accord, the Paris Agreement. In a recent study, we have examined the role of the EU’s leadership in this outcome. The EU’s attempts to realise its self-proclaimed bid for climate change leadership were scrutinised by investigating the extent to which the EU is actually recognised as a leader by potential followers and to what extent the EU has succeeded in achieving its negotiation objectives. To address these issues we utilised unique survey data collected at eight UN climate summits from 2008 to 2015 and evaluated the results of the UN climate negotiations particularly with respect to the Union’s goal attainment in Copenhagen and Paris.

In the eight years of our survey, the results show that, by a large margin, participants in the climate negotiations saw the EU, the US and China as the most influential leaders in these talks. However, based on this data we can see that the EU’s high self-conception of itself as a climate leader is not matched to the same degree by potential followers. The recognition of the EU declined from a height of 62% at the 2008 Poznan summit to 46% at the 2009 Copenhagen summit. After the disappointment in Copenhagen, EU diplomatic efforts to get a new negotiation mandate were recognised by the other participants and the EU returned to its status as the most recognised leader in Durban 2011 (50%), a position it held in 2012 and 2013 also. However, in 2014 at Lima and in 2015 at Paris it was replaced by the US as the most recognised climate leader.

Nonetheless, in every year of our survey the EU has been perceived to be one of the top three most influential leaders. However, the fact that no leader consistently was able to register over 50% support from potential followers, demonstrates that the world has lacked a single undisputed leader in the field of climate change. This is a situation that can be described as a fragmented leadership landscape and means the EU must adjust its leadership strategies in relation to other powerful actors, such as the US and China.

Chart: Percentage of participants in UN climate summits who viewed the EU, China, US, and G-77 as leaders in climate negotiations

Note: For more information, see the authors’ article in the Journal of European Integration

Six years after the debacle in Copenhagen, in which the EU’s leadership strategies failed to convince the world to support a binding treaty for top-down targets and timetables, the EU managed to forge enough of a leadership alliance with China and the US to achieve a universal deal designed to limit warming to below 2°C in Paris. A number of strategic changes by the EU contributed to this outcome. The EU became more flexible and realistic as to how a deal could be designed, agreeing to an institutional architecture that departed from the strict specified binding GHG emission reduction targets and timetables it pushed for in Copenhagen to a hybrid arrangement, which could be supported by the US and China, that had bottom-up, nationally determined reduction pledges combined with a rigorous international review of performance.

The EU also played a key role in the adoption of the Paris agreement through its efforts to create and build a High Ambition Coalition that pressured the major emitting countries to support an ambitious deal with concrete goals and a dynamic review process. This helped the EU to isolate potential veto actors, such as India, and allowed it to help gather the needed support that led to the approval of the Paris Agreement with a number of provisions that the EU worked hard to include. Namely, it has a stocktaking procedure that will take place every 5 years and a ratcheting mechanism that also requires countries to update their national climate plans to reduce emissions every five years as opposed to every 10 years as some countries wanted.

While the EU achieved many of its goals in Paris, the agreement has a number of shortcomings from an EU point of view. Although 185 countries in the run-up to Paris made commitments to reduce their GHGs (Intended National Contributions or INDCs), the caps on emissions are not binding and even if fully implemented will still result in warming of at least 2.7°C or more. Text on decarbonisation was removed and no date was given for fossil fuel use to peak and be phased out. Finally, not all of the agreement is legally binding, so future governments of the participating countries could try to wriggle out of the deal down the road.

Since the deal was struck two big developments have taken place. On the positive side, the Paris Agreement entered into force early on 4 November 2016, one month after 55 countries representing at least 55 per cent of global emissions formally joined the agreement. On the negative side, the 2016 election of Donald Trump means the continued participation of the US in the Paris Agreement or the UNFCCC is now uncertain. If the US drops out of Paris and withdraws from climate diplomacy and climate action, the EU will once again have to work hard to help fill the leadership void this will create and work to build on a constructive leadership alliance with China to help implement the agreement.

What do our findings mean more broadly for the EU’s ability to exert leadership as a global actor? Although our survey results and analysis suggest that while the EU may not be as influential as more structurally significant countries and while the EU’s positive role perception of itself as a world leader was not shared to the same extent outside of the EU, we can also demonstrate that the EU is far from the political pygmy some accuse it to be. Collective EU action in global affairs, particularly in the area of climate diplomacy, can be consequential in ways that could not be matched by the diplomatic engagement of any individual member state.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is based on the authors’ recent paper in the Journal of European Integration. It gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Charles F. Parker – Uppsala University

Charles F. Parker – Uppsala University

Charles F. Parker is Associate Professor of Political Science at the Department of Government and serves as a primary investigator in the Center for Natural Disaster Science at Uppsala University. His research has focused on climate change politics, the origins and consequences of the warning-response problem, and post-crisis learning and accountability procedures. His most recent publications include ‘Social Trust, Impartial Administration and Public Confidence in EU Crisis Management Institutions’ (with Thomas Persson & Sten Widmalm) in Public Administration, early view: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/padm.12295/full and ‘Complex Negative Events and the Diffusion of Crisis: Lessons from the 2010 and 2011 Icelandic Volcanic Ash Cloud Events’, (Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 97: 1 2015).

Christer Karlsson – Uppsala University

Christer Karlsson – Uppsala University

Christer Karlsson is Professor of Political Science at the Department of Government, Uppsala University in Sweden. He has published books, articles and book chapters in his principal research areas: climate change politics, European Union studies, constitutional politics and democratic theory. His work has appeared in journals such as European Law Journal, Global Environmental Politics, Journal of European Public Policy and Journal of Common Market Studies. He is currently doing research on political opposition in EU politics.