When appearing in the media, interest groups carefully frame their messages, but to what end? Anne Skorkjær Binderkrantz provides a cross-country comparison of the frames used by interest groups in the UK and Denmark. She focuses on the extent to which they portray their demands as furthering the interests of their own members, other societal groups, or whether they attempt to appeal to the public instead.

When appearing in the media, interest groups carefully frame their messages, but to what end? Anne Skorkjær Binderkrantz provides a cross-country comparison of the frames used by interest groups in the UK and Denmark. She focuses on the extent to which they portray their demands as furthering the interests of their own members, other societal groups, or whether they attempt to appeal to the public instead.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the British Bankers’ Association condemned the so-called ‘banker bashing’ and argued that the UK’s economic recovery would be impeded by a regulatory overhaul of the banking sector. Rather than emphasise the consequences of regulation to their members, the association instead sought to enlarge the issue by pointing to the effects such a course would have on the national economy. Similarly, Danish school teachers fighting a proposed rise in the number of class hours taught per teacher argued that this would adversely affect the quality of education. Again, the group chose to frame its concerns not by referring to the teachers but to the children and society.

Political actors carefully choose the way they present arguments, in the knowledge that fraiming affects the way the public perceive concerned positions and who decision-makers will support. But do groups focus on their membership, or try to frame their positions as being good for others or for society at large? To examine this question, I compare the arguments made by organised interests in Danish and UK newspapers.

There are compelling reasons to expect groups to point beyond their own members when making political appeals. The prominent US scholar E.E. Schattschneider argued that: “public discussions must be carried out in public terms” and that groups can mobilise support by making broad public demands. Still, interest groups are also membership organisations and their survival depends on maintaining and attracting members. This may require them to point out directly how the group works for its membership – also when appearing in the news media, where group members are likely to pay more attention than citizens at large. Interest groups can therefore be expected to balance these different logics when choosing how to present their messages.

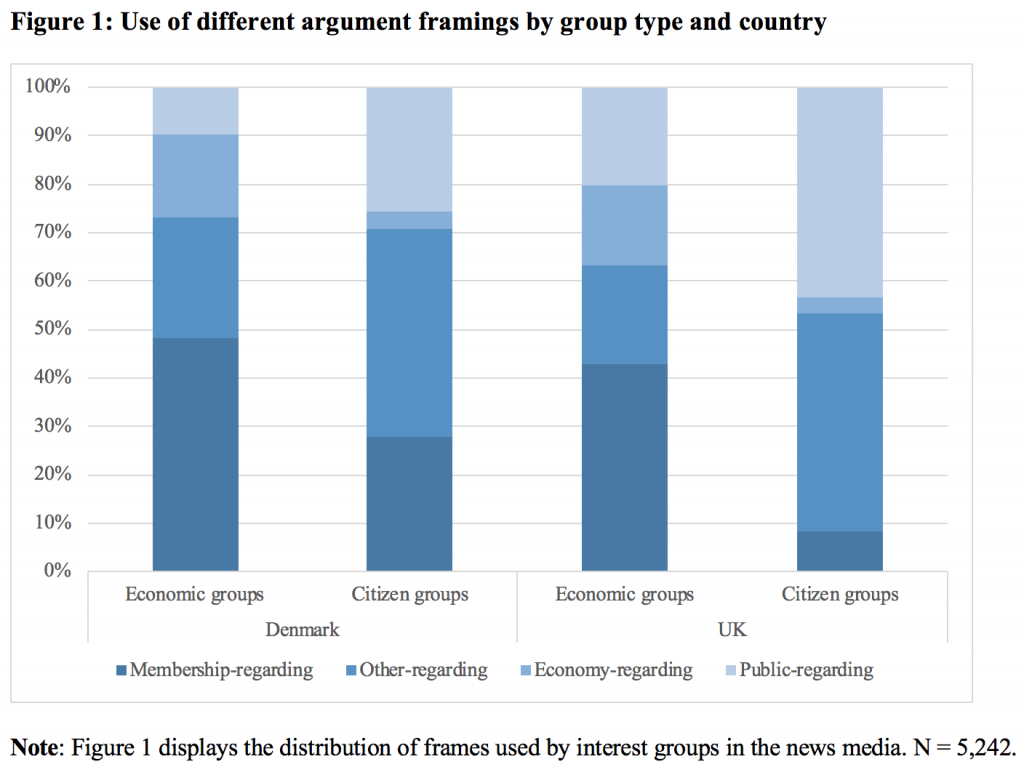

To shed light on how groups balance these concerns, the study tracks interest groups appearing in two major Danish and two major UK newspapers. Group messages were coded as focused on their own membership, other societal groups, the national economy or broad societal concerns. In total, the study includes more than 5,000 media appearances by groups in the two countries. Figure 1 displays the patterns of frame used across the two countries and economic groups vs. citizen groups.

It is notable that different types of frames are indeed at play, but also that variation is present across groups. For economic groups – for example business organisations and trade unions – it is most popular to focus on their own members. These groups are also prone to argue that their positions will strengthen the national economy. In contrast, citizen groups are more likely to point to consequences for other societal groups or society at large.

Interestingly, Danish and UK groups differ in their political communication. Danish groups – with a particularly large difference for citizen groups – are more likely to frame their concerns as being about their own members, while UK groups are more prone to point to broader aspects of their claims – as exemplified by the British Bankers Association above. Why is this the case? The most likely explanation is that it reflects different traditions for interaction between the state and organised interests – historical patterns of interest representation that affects present-day mobilisation and communication.

Denmark and the UK have very different political systems and traditions of interaction between interest groups and policymakers. Denmark is considered a corporatist political system with interest groups seen as representative of particular societal groups whose views they are expected to advance. In this type of system, the basic logic is that representatives of different interests are incorporated in public policymaking.

In contrast, the UK is a pluralist system, where the interest group system is relatively unstructured and different groups often compete to represent the same societal subgroups. The number of relevant participants in political processes is often high and power is less concentrated than in corporatist systems. Interest groups operating in pluralist countries can therefore not expect to be involved in public policymaking based on a representative monopoly, but instead need to argue convincingly that their viewpoints are worth supporting. In these different settings, it is not surprising that groups frame their arguments differently when they partake in policy debates.

More generally, this study shows how public debates are not always carried out in public terms. In fact, many groups focus on their own members when appearing in the national news media. It is also evident that media debates are framed differently in different countries. While Danish groups often talk about their own membership interests, their UK counterparts are more likely to frame their views with respect to other societal groups or broad, public interests. Future studies will show to what degree this affects the way policy debates are carried out in a broader sense.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying article in the Journal of European Public Policy

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article originally appeared at our sister site, British Politics and Policy at LSE. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain)

_________________________________

Anne Skorkjær Binderkrantz – Aarhus University

Anne Skorkjær Binderkrantz – Aarhus University

Anne Skorkjær Binderkrantz is Professor in the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University.