The latest efforts to deepen Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union have produced limited results, with Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker recently highlighting the role of Austria, Germany and the Netherlands in opposing reforms. Drawing on a new study, Silvana Tarlea illustrates the dynamics that underpin negotiations over Eurozone reforms. She explains that financial sector exposure has informed member state preferences for further European integration: the more exposed their financial sector was, the more likely countries were to support reform solutions leading to more European integration.

The latest efforts to deepen Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union have produced limited results, with Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker recently highlighting the role of Austria, Germany and the Netherlands in opposing reforms. Drawing on a new study, Silvana Tarlea illustrates the dynamics that underpin negotiations over Eurozone reforms. She explains that financial sector exposure has informed member state preferences for further European integration: the more exposed their financial sector was, the more likely countries were to support reform solutions leading to more European integration.

In a recent interview, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker accused Austria, Germany and the Netherlands of preventing Eurozone reform. But is this an accurate portrayal of the intergovernmental negotiations that took place during the financial crisis? What explained individual countries’ positions during these negotiations?

In a recent paper as part of the EMU Choices project, we narrowed this issue down to a few precise answers. Member states’ preferences were driven by economic self-interest. We collected and analysed data on negotiation positions from each EU member state on European monetary reforms between 2010 and 2015. We tested whether domestic politics dominated these negotiations or whether economic considerations mattered more. Our results show that financial sector exposure informed member state preferences for further European integration. The more exposed their financial sector was, the more likely countries were to support reform solutions leading to more European integration.

The data

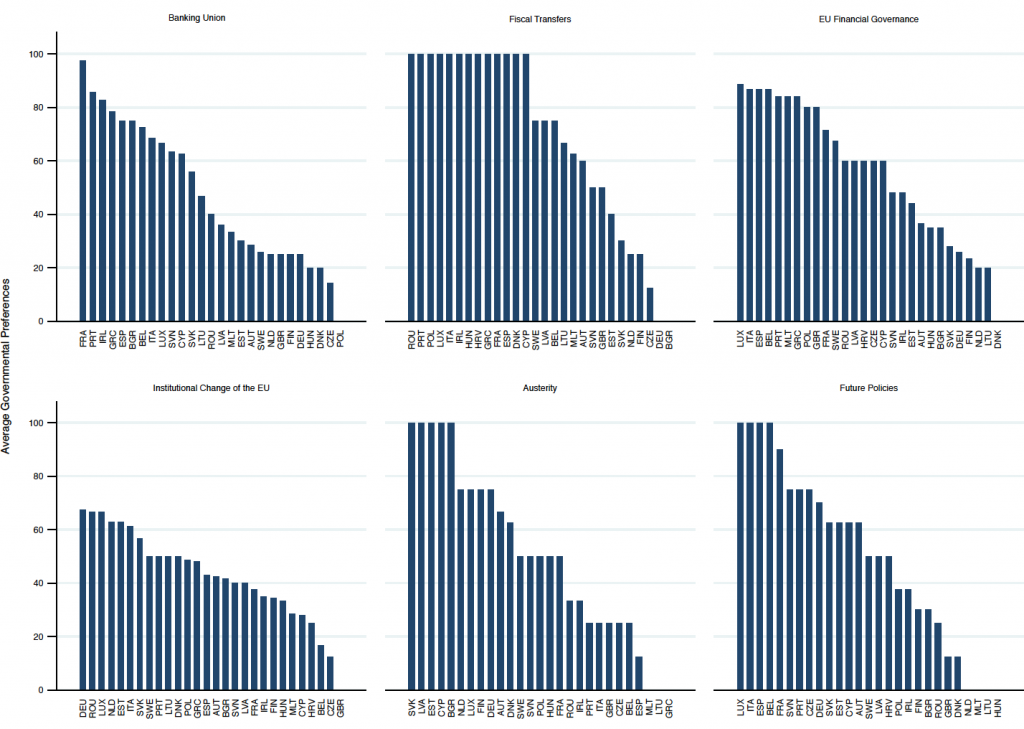

Within the project, scholars from nine countries collected systematic data based on documents and interviews on more than 40 issues that were discussed at EU level. The issues were scaled from 0 – representing the least ambitious reform proposals – to 100 – representing the most ambitious reform proposals leading to more European integration. The drivers of countries’ preferences during these negotiations were analysed by grouping these issues into six reform packages pertaining to the Banking Union, Fiscal Transfers, EU Financial Governance, Institutional Change of the EU, Austerity and Future Policies.

Figure: Average governmental preferences

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying article in European Union Politics (co-authored with Stefanie Bailer, Hanno Degner, Lisa M Dellmuth, Dirk Leuffen, Magnus Lundgren, Jonas Tallberg and Fabio Wasserfallen).

The figure above shows that with regards to the banking union, France was supportive of more power delegation to the EU, while Germany, Austria and the Netherlands were indeed less supportive. Similarly, regarding fiscal transfers, Greece was a full supporter of increased fiscal transfers, while Germany opposed more power delegation to the EU. In the last group on future policies, including the Five Presidents Reports and the Eurobonds, Luxemburg was supportive of the policies put forward by its former prime minister Juncker. Furthermore, when analysing these positions, we found that the greater a country’s financial sector exposure, the more likely this country’s government was to prefer more power delegation to the EU.

Financial market exposure shapes governmental preferences

More European solutions shaped as either more redistribution or a stricter regulation of national budgetary and fiscal policies can be considered a form of European integration. Our findings highlight that more economic interdependence in the Eurozone contributed to a stronger alignment of preferences. Moreover, domestic and European party politics played a smaller role than expected.1

We argue that governments act as risk minimisers, particularly during a crisis, and that they were mainly driven by national economic considerations when deciding on European monetary reforms. During the Eurozone crisis, different countries witnessed different degrees of economic vulnerability due to an uneven exposure of their banks to debtor countries. Seeking to minimise the risk of costly bailouts, countries with highly exposed financial sectors were more likely to support solutions involving high degrees of European integration. In contrast, political factors had no systematic impact.

When the bubble burst during the crisis, both debtor and creditor countries ended up with a related problem: debtors had to pay back their debts, while creditors were concerned about the ability to reclaim their assets. For the creditor countries, this entailed the risk of needing to bail out their heavily exposed banks and thereby significantly threatening their own budgets, possibly with major systemic impacts. In order to avoid such scenarios, both creditors and debtors had an interest in finding solutions at the European level.

In other words, the crucial question regarding a country’s preferences was not whether it was a creditor or a debtor country but rather the degree to which it was financially exposed to other EU countries by registering high claims or liabilities. Our findings reinforce the results of Armingeon and Cranmer that also show that economic structure, not political variables, explains variation in preferences.

European financial reforms are far from over. The tensions between the Italian government and the EU Commission about the Italian budget deficit in 2019 testify for this. We expect economic vulnerabilities to dictate future negotiation outcomes. Furthermore, if structural economic factors are relevant, one would expect financial de-risking to induce preference convergence and enable reform progress rather than different political actors in power.

-

We use a measure of the total non-consolidated financial sector liabilities as share of gross domestic product (GDP) in percent (Eurostat, 2017, see the Online appendix) to measure the liabilities incurred by private financial institutions in every member country of the EU. This indicator shows that the European sovereign debt crisis was first and foremost a private sector crisis (except for Greece).

For more information, see the author’s accompanying article in European Union Politics (co-authored with Stefanie Bailer, Hanno Degner, Lisa M Dellmuth, Dirk Leuffen, Magnus Lundgren, Jonas Tallberg and Fabio Wasserfallen)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Minister-president Rutte (CC BY 2.0)

_________________________________

Silvana Tarlea – University of Basel

Silvana Tarlea – University of Basel

Silvana Tarlea is a Senior Research Fellow (Oberassistentin) in Political Science at the University of Basel. She has a DPhil in politics from the University of Oxford, Nuffield College.

1 Comments