As a large currency union, the euro area sits between the two extremes of the US – with its high labour mobility and fully fledged federal fiscal union – and China – with its low labour mobility and central fiscal capacity. Corrado Macchiarelli and Fotis Mitropoulos write that while the US is normally regarded as a benchmark for integration in the euro area, there are potentially lessons that can be learned from China’s experience, particularly on the question of whether labour mobility is a necessary condition for a currency union to work.

As a large currency union, the euro area sits between the two extremes of the US – with its high labour mobility and fully fledged federal fiscal union – and China – with its low labour mobility and central fiscal capacity. Corrado Macchiarelli and Fotis Mitropoulos write that while the US is normally regarded as a benchmark for integration in the euro area, there are potentially lessons that can be learned from China’s experience, particularly on the question of whether labour mobility is a necessary condition for a currency union to work.

Unemployment rates have now returned to levels comparable to before the financial crisis in most advanced economies, including in the US, China and the EU. There are significant differences in the volume and duration of these fluctuations across countries, however: looking at the EU in comparison to the US and China, at the end of 2018 while China’s unemployment rate fell to a 20-year low (3.8%), and the US exhibited lower unemployment rates than in the pre-crisis period (3.9%), the EU recorded its lowest rate since 2008 – 6.8% at the end of 2018, and 6.2% in August 2019 – still comparably higher than its peers. Diverging unemployment rates across EU countries and regions have become the sign of a dysfunctional labour market recovery and rising disparities within the Union.

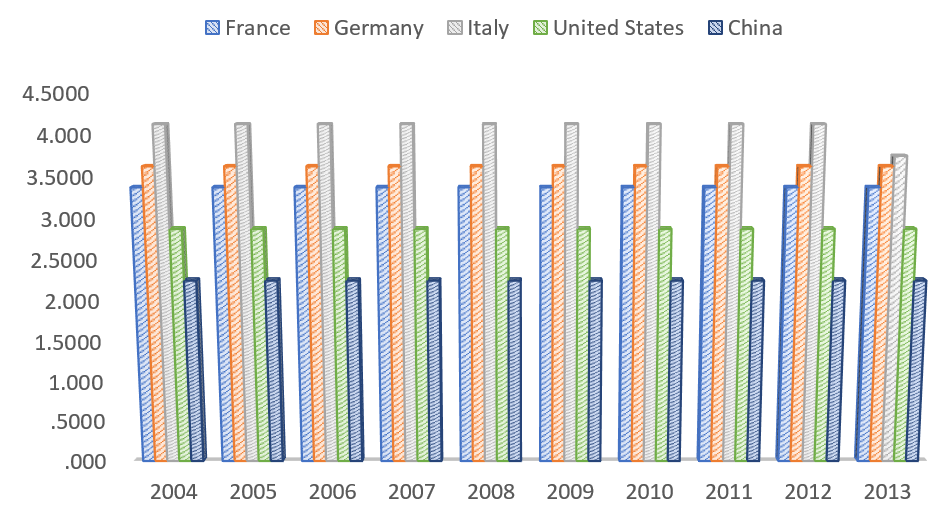

Figure 1: Strictness of employment legislation – collective dismissals

Source: OECD Stats

According to Optimum Currency Area (OCA) theory, a country should achieve a sufficient level of trade-openness, labour flexibility and synchronicity of business cycles for the benefits of its membership to exceed its costs. From a euro area perspective, the US is typically regarded as a benchmark as it presents high domestic mobility of labour and a fully federal fiscal policy. The decisive role of labour mobility and institutions in easing adjustments to Optimal Currency Area shocks have been extensively discussed in the literature. Particularly, in the absence of (or with limited scope to use) fiscal policy in Europe, it is advocated labour mobility should be at a sufficient level to compensate for adverse idiosyncratic shocks.* However, this is far from being the case and it is widely acknowledged that one of the symptoms of lower labour mobility in continental Europe is due to high employment protection legislation as measured by the OECD (Figure 1). The latter is, however, possibly a poor measure for regional mobility, rather capturing intra-sectoral flows and the extent to which people make transitions in and out of jobs.

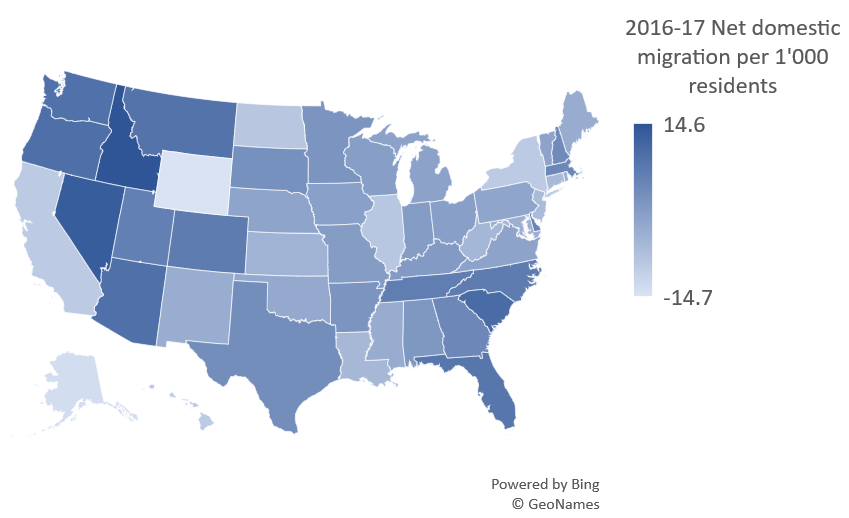

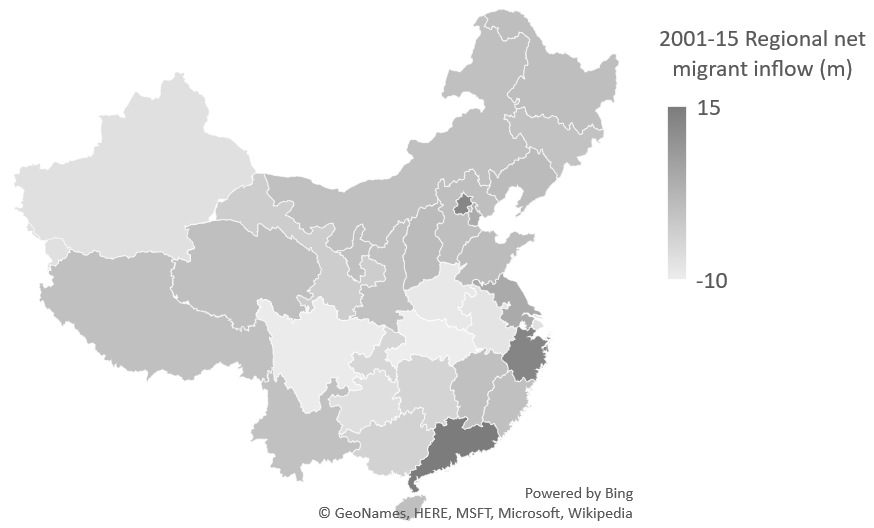

Many researchers have analysed the decline in movements in the US and the rapid rise in migration across Europe and China. For that, China represents a special case because the labour market is not fully geographically integrated and important restrictions on regional labour mobility exist. The labour market reforms implemented during the last 30 years have played a very important role: in particular, the shut down in 1997 of inefficient state-owned enterprises (SOE) with consequent lay-offs, and the Hukou reform in 2000 to facilitate rural-urban migration. As a result of these reforms, rural migrant workers in the cities increased rapidly (Figure 3). Over the period 2001-15, migrant flows were predominantly in the direction of eastern coastal provinces (Figure 2). According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, these historical migration trends are expected to shift in the future though, with a projected fall in volume in the net migrant inflows to eastern coastal provinces to around one-third of the level observed in 2001‑15.

Figure 2: Regional migration net flows

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit, Bruegel based on Eurostat, US Census Bureau

Figure 3: Urban population (% of the total population)

Source: Eurostat

By contrast, the US labour market adjustment process has been traditionally faster than in Europe and China due to higher labour mobility and the remaining lower barriers in the labour market. The role of migration in the economic adjustment process has thus played a role in the US. The US Census Bureau releases its population estimates for each of the 50 states: according to the data in Figure 2, the picture is consistent with historical population migration trends in the US: Northeastern and Midwestern states have lost population to domestic migration, whereas, Western and Southern states mostly saw net positive flows.

Previous studies have argued that migration between European countries increased after the introduction of the euro and the recent financial crisis. This said, however, the adjustment process in the EU is substantially different to the one in the US and China. The differences in cultural, language and institutional barriers are inhibitory factors to labour mobility. Divergence among countries and regions remain significant and, in the absence of explicit European labour market policies (euro-wide unemployment insurance or social security, which would – in turn – require fiscal backing), European countries, and those sharing the single currency in particular, are not well-equipped to react to asymmetric effects of demand shocks.

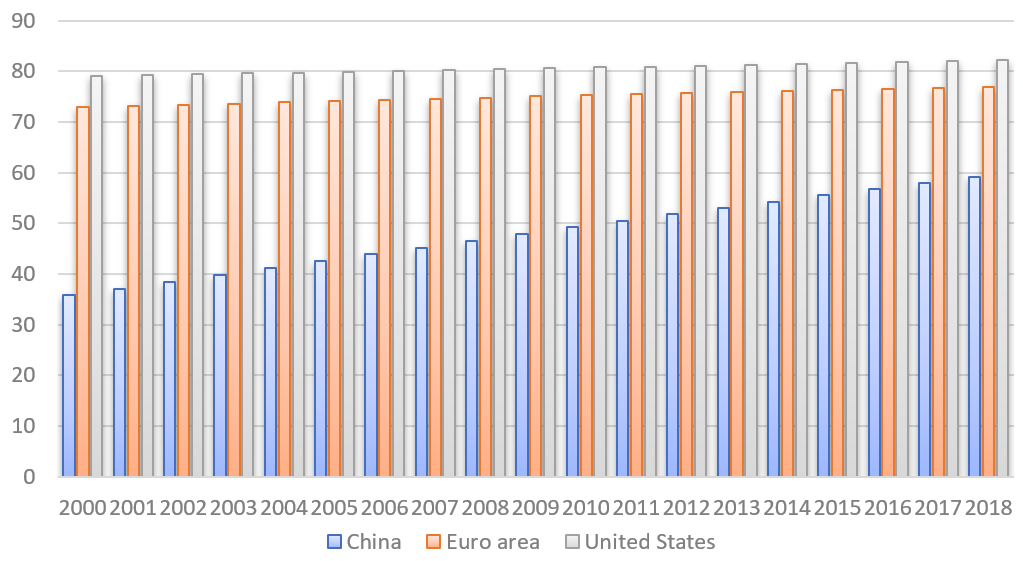

After the outbreak of the crisis, several programmes have been implemented with the aim of reducing rigidities in the labour market. Still, mobility remains competitively low (Figure 4; see also European Commission). According to the think tank Bruegel, after the crisis most of Southern Europe still experienced a cumulative net gain in intra-EU migration flows. However, over the most recent years, 2013-17, with a still-weak recovery on the way, the picture has changed for countries such as Spain and Italy, which are experiencing negative net flows. In contrast, Germany, the UK and, to a lesser extent, Sweden, seem to be making most of the gains (Figure 2).

Figure 4: EU mobile citizens of working age (20-64) by country of citizenship (% of their home-country resident population)

Source: Eurostat

China is less integrated as an Optimal Currency Area than the US, but at the same time, it is much more integrated than the euro area. Yet, at those two extremes, the US and China do not have the same problems as the euro area. The existence of multiple taxation systems, national sovereignty and different cultures slow down the economic and social deepening of the EU. China acts more as an OCA because it has historically overcome those problems.

With this said, however, China’s divergences among provinces are not negligible, as there exists inequality among poorer and richer provinces. Furthermore, the existence of provincial fiscal policy seems to have amplified provincial business cycles, thus increasing the degree of regional cyclical idiosyncrasies. As Chinese economic growth currently slows down, the implications of an adjustment programme become even more relevant for China, with many observers pointing to the need for a rebalancing process. The evidence regarding the process of rebalancing is in fact mixed: China has made significant progress in external developments while internal rebalancing still needs a faster pace of adjustment, possibly using a monetary-fiscal mix. On the other hand, labour market adjustment in China has started to react to the reforms of previous years. For the sixth consecutive year, the number of newly created jobs in urban areas passed the 13 million mark, amid moderate economic growth and external uncertainties.

It should be mentioned that different labour market features in China, Europe and the US are also linked to the power of union and labour protection and the degree of unionisation. Chinese unions were not independently established by workers and the government has recognised only recently the role of labour legislation by encouraging unions to play a significant role in the protection of workers’ rights and in the negotiation of collective contracts. Moreover, at the macro level, the unemployment rate has typically been more cyclical in the US over the last two/three cycles, while in the EU it has rather been tied to structural and country-specific features, with demand recognised to be lower and shocks thought to be comparatively more enduring and asymmetric. That certainly hinges on the possibility of an even labour market recovery in Europe. China, on the other hand, experienced economic progress over the last four decades mainly due to demographic expansion of the population and labour surplus. Nowadays, there is a consensus that the “unlimited” labour supply experienced after the boom years has been drastically reduced, with the main reason being a diminished supply of extra labour from the rural provinces that have traditionally provided it.

To conclude, Modern China could represent a useful example for Europe of a currency union with little labour mobility. Labour mobility in China is very limited, although not facing constraints such as institutional, cultural differences, but mainly due to a system with barriers to mobility. In a currency union such as China, labour mobility does not seem to be a necessary (nor sufficient) condition for the union to work. In China, political/fiscal union seems to be crucial instead: there is consensus that the reforms implemented in the previous years in China have been accelerated by the fiscal union.

The euro area delay in implementing any sort of fiscal consolidation certainly reduces the chances for internal rebalancing: one of the union’s major challenge will thus be to overcome its lack of a mechanism for fiscal transfers and risk-sharing among member states. While more regional migration is clearly desirable, one can speculate that achieving fiscal solidarity could be a more durable solution as China’s example would seem to suggest.

* Differently from other demographic factors, such as natality and mortality rates, net regional migration is zero-sum: e.g., for intra-EU flows, everyone who moves to a country from another EU country necessarily leaves its country of origin. This is recorded as a +1 in the recipient country and a -1 in the country of origin.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Images Money (CC BY 2.0)

_________________________________

Corrado Macchiarelli – Brunel University London / LSE

Corrado Macchiarelli – Brunel University London / LSE

Corrado Macchiarelli is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Economics and Finance, Brunel University London, and Visiting Fellow at the London School of Economics’ European Institute.

Fotis Mitropoulos – Democritus University of Thrace

Fotis Mitropoulos – Democritus University of Thrace

Fotis Mitropoulos is a Postdoctoral student on “Macroeconomic adjustments and Labour markets in the US, Europe and China” at the Democritus University of Thrace.

Are shocks and stabilisations worth to a locale economy? If China is generated as employment flux, what is the net worth of German, Swedish (etc.) assets to a down-sized sector of British economy. The last that China emerged as a world economy, employment levels equaled world production according to Mao Tse-Dong theory. Britain then abolished the corvee system and like Wilberforce began to extract large amounts of debt from their fiscal plans for an international system of state-owned reform (Malthus and Weber). Are there perfect regimes of capital? How can England downsize Hong Kong labour costs when the economic state in China is headed for an employment revolution? When is growth ideally going to diminish labour. Some issues of policy when China returns Communism as an urban deterrent to utopia.