Germany will mark the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November. Martin J. Bull writes that alongside the sweeping changes that occurred in central and eastern Europe, the end of the Cold War also had a lasting legacy for western European states. While the demise of western Europe’s communist parties after 1989 appeared to signify the passing of a burnt-out cause, it acted as a catalyst for change in the political space to the left of social democracy, generating new ideas and configurations that continue to shape politics today.

Germany will mark the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November. Martin J. Bull writes that alongside the sweeping changes that occurred in central and eastern Europe, the end of the Cold War also had a lasting legacy for western European states. While the demise of western Europe’s communist parties after 1989 appeared to signify the passing of a burnt-out cause, it acted as a catalyst for change in the political space to the left of social democracy, generating new ideas and configurations that continue to shape politics today.

On 9 November, the world will celebrate the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the most potent symbol of the end of the Cold War. The main focus of that anniversary will likely be on the changes that have occurred in the politics of the former communist states. Yet, the impact of this monumental event was as great in the west as the east, with many changes so profound that we are still living with them today.

One of these has been the little-noticed fate of the non-ruling West European Communist Parties, a distinctive ‘party family’ (known as WECPs) that was born out of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the split in the social democratic movement it entailed. WECPs had, for over 70 years, been dedicated to the overthrow, or at least transformation, of western capitalist societies ‘from within’, their heyday being the years of so-called ‘Eurocommunism’ when – for a brief time in the 1970s – the Italian, Spanish and French communist parties enjoyed a rise in their electoral fortunes on the back of a partial alignment of their programmes for government.

Yet, it never happened, and the 1989 revolutions in central and eastern Europe brought an abrupt end to western communism – at least as we knew it. Surely, the argument went, there was no further purpose these parties could serve, no further rationale for their continued existence and no further reason for the historic social democratic/communist split – was there? In one sense – the immediate short-term – developments appeared to respond to the conventional rationale. Western communist parties immediately after 1989 became, in the parlance, ‘post-communist’ parties, the individual parties themselves became divided in their responses to the end of the Cold War, and the WECP family quickly ‘died’ in the early 1990s.

Yet, at the same time, few of the parties that had comprised that party family were prepared simply to accept ‘social democracy’ as their new reference point, if only because social democracy was confronting its own difficulties in the late 1980s and did not escape what was an existential crisis for all left-wing parties (and politics) in 1989, tarnished in the public image as they were by domestic programmes and international policies widely seen as out of date if not dangerous, and confronted with a phase of increased hostility from neo-liberalism and its variants.

Most of the former western communist parties and their successors, therefore, saw the fall of the Berlin Wall and the disappearance of the suffocating embrace of the Soviet Motherland less as a reason to fold than to experiment with something new. They were determined to keep ‘radical’ left-wing politics alive, transforming the political space to the left of social democracy. In doing so, they ‘joined’ two other traditions which had pre-dated the fall of the Berlin Wall and which had attempted to challenge the monopoly of western communist parties in the previous two decades: the (primarily extra-parliamentary) ‘New Left’ movement of the late 1960s and 1970s and the ‘New (or Green) Politics’ movements of the 1970s and 1980s. The destruction of western European communism as a party family, therefore, acted as a genuine catalyst to the overall transformation of the political area to the left of social democracy.

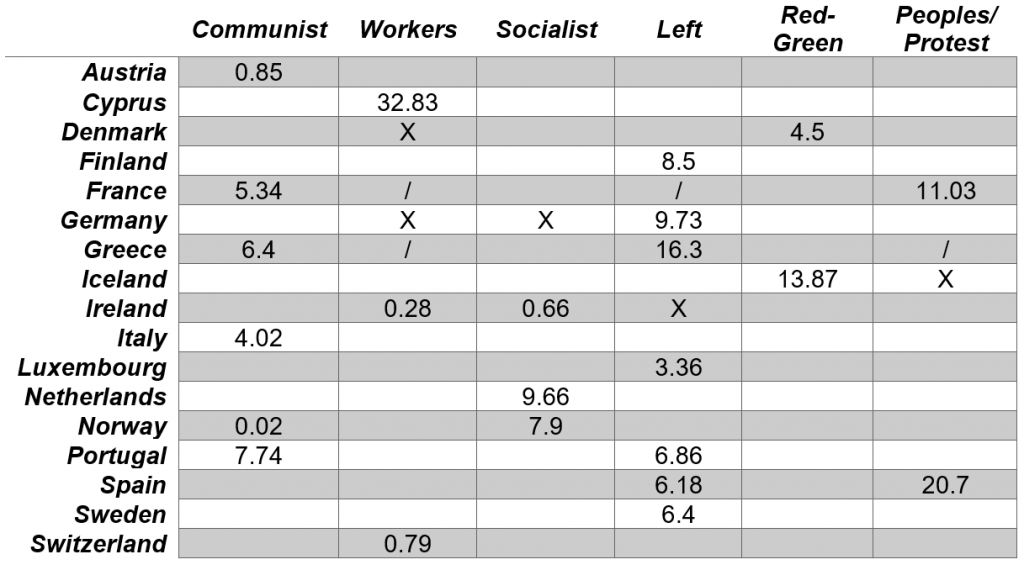

Thirty years on we can observe an extraordinary diversity of radical left parties across Europe in terms of their sociological origins and nomenclature (communist, Proletarian, worker, socialist, left, Red-Green, Peoples/social protest), characterised by a rich array of programmatic stances (some of which go beyond the traditional left-right spectrum), diverse organisational forms and a willingness to enter into coalition with other parties – all of which makes them stand out from their western communist forbears, even where the communist name lives on (in Austria, France, Greece, Italy, Norway and Portugal) (see the table below).

Table: Radical left parties in Europe since 1989: Indicative electoral size by nomenclature and country

Note: The figures show indicative electoral size for each party (the average share of the vote in the lower house from 2000-2015); X = radical left party or parties in existence after 1989 but now defunct; ̸ = Radical left party or parties in existence, but not having presented candidates for lower house. Source: Derived from M. J. Bull, ‘The radical left since 1989: Decline, transformation and revival’ in E. Braat & P. Corduwener (eds), 1989 and the West, Western Europe since the End of the Cold War (Routledge, 2020).

The electoral performance of these parties, moreover, has seen a revival in the past decade which would never have been anticipated in the first twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Those years were characterised by an electoral decline under the apparent exhaustion of the Marxist project and the concomitant roll out of the neoliberal, globalisation agenda. The radical left’s rejection of the ‘inevitability’ of that agenda only began to see fruit after the economic crash of 2008 and the widespread imposition of austerity measures by national governments and the European Union. Radical left parties in Greece, Denmark, the Netherlands, Portugal, Germany and Finland have all witnessed a rise in their electoral and political fortunes, based, it seems, on a curious alliance between their traditional, Eurosceptic supporters and those who are pro-EU but are increasingly dissatisfied with the EU’s imposed austerity drive. In that sense, anti-austerity politics has also given these parties a ‘big idea’ or a ‘meta-narrative’ around which to identify and act as a magnet for support.

Of course, there is much work for these parties still to do. Frontal opposition to austerity politics is not, in and of itself, a foundation for long-term sustainability. But radical left parties can, on 9 November, look back with some pride at their achievements. Thirty years ago, their western communist forebears had been widely viewed as the ashes of a burnt-out cause. But western communist parties had never comprised the entirety of the experience of radical left politics, and their passing acted as a catalyst to a veritable sea change in the political space to the left of social democracy, generating new ideas and configurations that are still present – and reverberating – today.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Mike (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

_________________________________

Martin J. Bull – University of Salford

Martin J. Bull – University of Salford

Martin J. Bull is a Professor of Politics at the University of Salford and author of ‘The radical left since 1989: Decline, transformation and revival’ in E. Braat & P. Corduwener (eds), 1989 and the West, Western Europe since the End of the Cold War (Routledge, 2020).