In Resist: Stories of Uprising, editor Ra Page brings together contributors to offer an anthology of short stories and critical essays that narrate a rich counter-history of resistance in the UK, spanning from the Boudicca Rebellion to the protests in response to Grenfell Tower. Positioning fiction as a radical medium, this is a valuable book that will be of particular interest to participants and scholars of social movements, writes Chris Waugh.

Resist: Stories of Uprising. Ra Page (ed.). Comma Press. 2019.

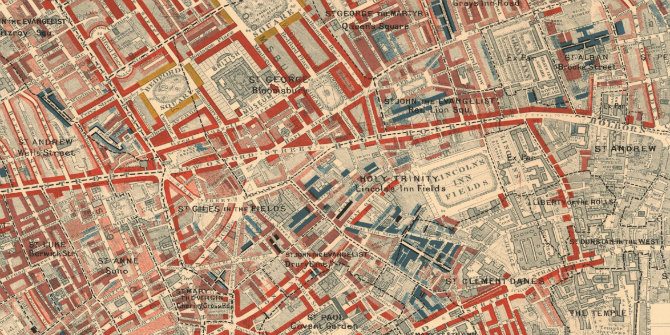

Writing towards the end of his life, Michel Foucault identified the importance of ‘counter-history’ as a tool for radicals. Counter-history refers to ‘the ability to identify omissions, to listen to silences, to play with discursive gaps and textual interstices as a crucial part of our critical agency for resisting power/knowledge frameworks’ (José Medina, 2011, 6) – that is, to draw attention to, and learn from, the aspects of a collective history that are overlooked, and provide resources and knowledge for contemporary strategies of resistance. With this in mind, Resist: Stories of Uprising, an anthology of short stories and critical essays about resistance in the UK, is an excellent example of such a counter-history. The book not only draw conceptual links between seemingly disparate occurrences of political uprising throughout the history of the British Isles – from Boudicca’s rebellion via the Cato Street Conspiracy to the protests in response to Grenfell Tower – but also offers a sense of historical and collective solidarity for radicals today.

Writing towards the end of his life, Michel Foucault identified the importance of ‘counter-history’ as a tool for radicals. Counter-history refers to ‘the ability to identify omissions, to listen to silences, to play with discursive gaps and textual interstices as a crucial part of our critical agency for resisting power/knowledge frameworks’ (José Medina, 2011, 6) – that is, to draw attention to, and learn from, the aspects of a collective history that are overlooked, and provide resources and knowledge for contemporary strategies of resistance. With this in mind, Resist: Stories of Uprising, an anthology of short stories and critical essays about resistance in the UK, is an excellent example of such a counter-history. The book not only draw conceptual links between seemingly disparate occurrences of political uprising throughout the history of the British Isles – from Boudicca’s rebellion via the Cato Street Conspiracy to the protests in response to Grenfell Tower – but also offers a sense of historical and collective solidarity for radicals today.

In Ra Page’s excellent and concise introduction, he makes the prescient point that throughout history, protesters are ‘othered’. Media narratives have fixated on peculiar specificities about protesters – ‘the strangeness of [their] clothes, their hairstyles, or other aspects of their lives’ – and positioned protesters outside of the bounds of acceptable society: the protester is always seen as ‘outside the law’, an alien entity or an intruder. One can see this clearly in contemporary politics in the panicked discourse around Antifa movements, with the often-repeated anti-Semitic myths of ‘Soros-funded’ protesters: that is to say, permanent outsiders unwilling to participate in some vaguely defined ‘social contract’. Dominant powers will, according to Page, always seek to portray protesters as un-relatable and dangerous figures. Similarly, across the years, times of insurrection are accompanied by a fetishisation of law enforcement, and an increasing willingness to take decisive measures against those ‘other’ figures – protesters included. Thus, protesters and activists become excluded from the ‘social contract’ – and their motivations, their narratives and their stories become lost.

The blend of fact and fiction in this volume (or, as the sleeve make it clear, ‘well researched, historical fiction’) offers a useful consideration of the role of narratives in radical politics. Scholars of social movements have, over the years, identified the position of narratives and storytelling in protest movements. Stories in movements tend to concern past examples of insurrection, of interactions with law enforcement, of past splits and attempts at a united front – yet these stories are not simply for entertainment value. As Mattias Wahlström (2011) put it:

Storytelling is thus an important mode of social control in the maintenance of conformity. When told to other movement participants, narratives and protests, and responses to the behaviour of authorities are no exception […they] prescribe the appropriate frames and vocabularies of motive to use.

Activist stories, in this sense, help shape activist mentalities, frame systems of value and contextualise the struggles of today. However, as Francesca Polletta (2006) has argued compellingly, narratives and stories of protest are not exempt from being co-opted, misused and utilised by dominant powers – especially media and state powers – against the movements who authored them – against their own writers and protagonists if you will. Thus, any movement that tells stories will risk those stories being used to damn them, as illustrated by the example Page gives of protesters being ‘othered’.

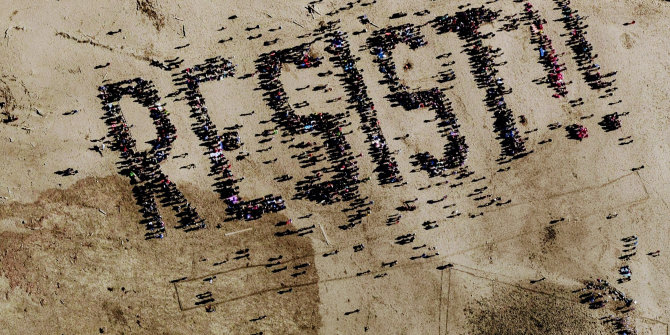

Credit: Tim Gouw on Unsplash

The utility – and also precarity – of activist narratives is precisely what makes Resist such a valuable book to social movement participants and those of us who study movements. Against a dominant narrative about the apathy of British people, the volume draws together a rich counter-history of resistance from the Boudicca Rebellion to the response to Grenfell Tower. Each story, followed by a brief historical and analytical essay about the events it describes, blurs the boundaries between politics, sociology and history. Indeed, the stories themselves are of a consistently high literary quality, and more importantly, do vital work in finding the human element in mass protests and key historical moments of insurrection. Martin Edwards’s excellent retelling of the Peterloo Massacre, ‘The Cap of Liberty’, for example, not only captures the hope, dreams and despairs of those who assembled in St Peter’s Field in Manchester in 1819, but also functions as a gritty, visceral narrative of revenge and intolerance of intolerance. Similarly, Karline Smith’s ‘The Whistling Bird’ tells a touching love story against the backgrounds of racial tension and the Notting Hill Riots of 1958. In this sense, Resist fits into its own radical tradition of William Morris and others: the use of fiction as its own form of radical medium.

While the literary efforts are excellent throughout, some of the critical essays fall short. Chris Cocking’s essay on the 1996 Newbury Pass protests offers a scant political and historical analysis of an overlooked incidence of resistance, instead focusing more on the author’s own involvement in the protests. This is not to say that activist-scholar narratives aren’t useful – in some cases, extremely useful – but Cocking appears to have overlooked the scholar side of the identity. This is a shame, especially since his essay follows the beautifully told ‘198 Methods of NVDA’ by Gaia Holmes.

Of equal value in the volume is the foregrounding of the idea that what is ‘radical’ is a relational idea, tied to the value system of the current historical moment, as Giorgos Charalambous and Gregoris Ioannou (2019) have compelling argued elsewhere. At the time of writing, the British media is preoccupied in many quarters with the idea that the Labour Party lost the 2019 General Election because it was ‘too radical’; yet Resist draws attention to the fact that for many centuries, the idea of the working class voting, of trade unions, of interracial relationships and so on, were also once ideas considered radical and their proponents subject to verbal abuse, imprisonment and police violence.

The final story of the volume is a retelling of the scandalous and devastating fire at Grenfell Tower in 2017 – a matter which, to this day, has resulted in no criminal prosecutions; many of the families affected by the blaze are still, two years later, in temporary accommodation. That this continues to be a site of resistance and ongoing struggle serves to confirm to the reader that radical battles are still being waged. In many ways, the volume seeks to remind its activist readers that with many of the struggles and insurrections we fight today – issues which are seen as radical to our era of right-wing populism and nativism – we are never asking the earth. Indeed, future generations will in all likelihood look back on us and wonder why our demands were ever subject for debate.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is provided by our sister site, LSE Review of Books. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Chris Waugh – University of Manchester

Chris Waugh is a Doctoral Researcher at the School of Sociology, University of Manchester. His research focuses on masculinity, militancy and misogyny within UK socialist groups.