Economically powerful individuals are assumed to have greater capacity to influence politics than those with lower incomes. This might imply that as economic inequality increases, we should see a growing representation gap between rich and poor. Yet as Derek A. Epp and Enrico Borghetto explain, previous research has produced a mixed picture, with lobbyists that have the most financial backing often failing to secure policy victories. Drawing on a new study, they suggest the influence of inequality may be more visible when it comes to keeping issues off the political agenda: they find evidence that higher levels of inequality are associated with less legislative attention being directed toward the policies most likely to generate a downward redistribution of wealth.

Economically powerful individuals are assumed to have greater capacity to influence politics than those with lower incomes. This might imply that as economic inequality increases, we should see a growing representation gap between rich and poor. Yet as Derek A. Epp and Enrico Borghetto explain, previous research has produced a mixed picture, with lobbyists that have the most financial backing often failing to secure policy victories. Drawing on a new study, they suggest the influence of inequality may be more visible when it comes to keeping issues off the political agenda: they find evidence that higher levels of inequality are associated with less legislative attention being directed toward the policies most likely to generate a downward redistribution of wealth.

How does money influence democratic politics? This age-old question has taken on a new urgency as economic inequality has grown in democracies around the world. One idea is that by mobilising their capital resources, wealthy elites can tip the scales of policymaking in their favour, often at the expense of labour or those with less. For example, in the wake of the 2008 recession, after embarking on costly bailouts of insolvent financial institutions many governments attempted to balance budgets through austerity measures. Commentators noted that these measures received little support from economic scholarship and speculated that they became popular mainly because policymakers were hesitant to alienate the financial institutions many deemed responsible for the crisis.

Intuitively, the idea that economic disparities translate to political ones makes sense. At the very least, money can buy you time to pay attention to politics. Thus, as inequality increases, so too would the political “representation gap” between the rich and everyone else. However, studies on lobbying and campaign donations in the US paint a more complicated picture. Often, lobbyists with the most financial backing fail to procure meaningful policy victories. Moreover, candidates and political parties mostly receive donations from their natural allies. That is, from groups or individuals that already agree with them politically. Is it the donation that is driving subsequent political action or does the causal arrow flow the other way? It’s hard to say and it appears that only in rare circumstances can political spending be clearly identified as a key factor in lawmaking.

The “second face” of power

Has the importance of money and inequality to politics been overstated? Probably not, although we may be looking in the wrong places. We argue that it is less about the policies that are passed and more about the ones that are not.

This is actually an old idea. Foundational theories in policy studies concerned the nature and distribution of political power. A major insight from this tradition was that power can be exercised through non-decision making. If direct power is the ability to put an issue on the policy agenda and get your solution approved, then at least as important is the power to do the opposite, which came to be known as the “second face” of power. This process can occur directly by lobbying against the inclusion of a particular issue on the agenda or, more implicitly, by crowding an issue off the agenda by assigning it lower priority. The chief distinction is that while the first face of power occurs openly, the second is more surreptitious as it consists of strategic gatekeeping decisions that reinforce the rules or institutional norms that prioritise some issues over others.

We investigate how the second face of power might shape legislative agendas during periods of heightened economic inequality. We argue that economic elites act as agents of inaction and non-decision, shaping the course of policy agendas to direct legislative attention away from issues that they find overly disruptive and to protect the status quo. This means keeping policies that would create downward redistributions of wealth off the agenda.

Measuring legislative agendas

To test this hypothesis, we assemble data on the legislative agendas of Denmark, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Belgium, and the United States over variable lengths of time but spanning multiple decades for each country. The source of this data is the Comparative Agendas Project, which uses a uniform coding system to track the amount of legislative activity surrounding different policy areas over time. Researchers from each country code activities into only one policy category and it is therefore possible to compare trends in political attention to different issues both cross-nationally and over time. We focus on activities deriving from two distinct stages of the agenda: bills introduced for legislative consideration and public laws. We group legislation relating to the affordability of health care, unemployment, social welfare programmes, pension plans, workforce development, labour unions, and public housing together into a “social safety-net” group. Our logic is that these are the policy topics most likely to generate downward redistributions of wealth.

The question then is a simple one: how does legislative attention to redistributive policies relate to economic inequality? Plausibly, inequality could generate more attention to these issues. After all, these are the policies most likely to mitigate inequality and the public appears concerned. A 2014 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center found that 65% of US respondents agreed that the gap between the rich and everyone else had grown, and 69% thought government should do something about it. Meanwhile, Pew’s 2014 Global Attitudes survey revealed that 60% of Europeans see inequality as a “very big problem” and another 31% see it as a “moderately big problem.” We might therefore expect legislative attention to be drawn toward the types of redistributive solutions that would alleviate public concern.

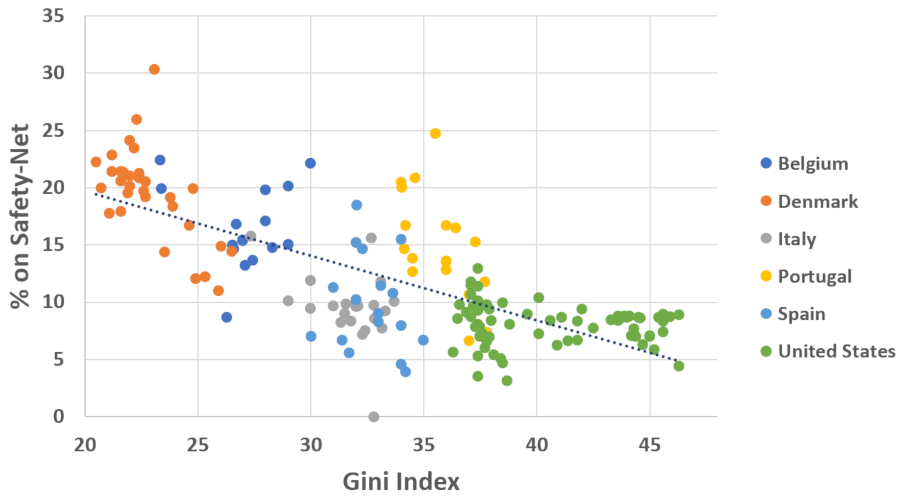

This is not what we find. Figure 1 shows the percentage of total bills introduced in a legislative session on safety-net topics juxtaposed with the Gini Index, which is a common measure of economic inequality. Higher values on the Gini Index indicate a greater concentration of income. The correlation is strongly negative, meaning that higher levels of inequality correspond to less legislative attention going to safety-net policies. Figure 1 plots data from all six countries together, but the relationship for each country individually is also negative, so it is not simply an artefact of the aggregation.

Figure 1: Relationship between legislative attention to safety-net topics and inequality

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of European Public Policy

Of course, we might anticipate that countries that neglect safety-net policies would experience higher levels of inequality. We find, however, that the relationship shown in Figure 1 is highly robust to time trends, political and economic factors, existing levels of social spending, and different governing structures. Using regression models to control for all these things, we still find that an uptick in inequality predicts a decrease in attention to safety-net policies. This is true for bill proposals and for public laws.

Inequality and the policymaking environment

If policymakers are interested in combating inequality, then it is plausible that attention would gravitate toward safety-net policies when and where inequality is more acute. In reality, our results point in the opposite direction: higher levels of inequality are associated with less legislative attention to those policies most likely to generate a downward redistribution of wealth.

What could produce such a pattern? With existing data we can’t say for certain, but it is certainly consistent with the longstanding idea that economic elites constrain the scope of decision-making by crowding out certain policies from the agendas of policymakers. Thus, the empirical evidence supports our hypothesis and, chiefly, demonstrates the importance of considering not only policy enactments but also how the agenda-setting landscape more broadly responds to economic stratification. What is more, we show that these broad agenda-setting trends apply both in US and European context, thus responding to a recent appeal in the literature on the politics of inequality for more comparative work.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of European Public Policy

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Derek A. Epp – University of Texas at Austin

Derek A. Epp – University of Texas at Austin

Derek A. Epp is an Assistant Professor in the Government Department at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on agenda-setting, criminal justice, and economic inequality.

Enrico Borghetto – Nova University of Lisbon

Enrico Borghetto – Nova University of Lisbon

Enrico Borghetto is currently a Research Fellow at the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (IPRI) and the Interdisciplinary Centre of Social Sciences (CICS.NOVA), Faculty of Social and Human Sciences, Nova University of Lisbon. His research has focused on the Europeanisation of national legislation, legislative studies and agenda-setting.