Covid-19 has once again put EU solidarity to the test. Nadia Petroni writes that while much of the focus has been on the pandemic’s impact on healthcare and the European economy, it has also pushed states further apart on the issue of irregular migration.

Prior to the Covid-19 outbreak, the issue of irregular migration had been at the top of the EU’s political agenda for over a decade. At the same time, the governance of migration proved to be the most complex and problematic area of governance in the EU due to the multiplicity of interests within the Union which are in constant flux.

Disagreement between EU leaders was brought to the fore during the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ of 2015-17 when the EU received the largest influx of irregular migrants since the end of the Second World War. Consequently, EU institutions and member states were unable to forge a common approach to deal with the crisis. Indeed, rather than developing a long-term strategy, a series of short-term ad hoc measures were implemented, which ultimately failed to alleviate pressure on those member states facing high migration pressures.

The EU’s inability to develop a coherent response to the crisis resulted in political cleavages both between and within the national and supranational levels. This was primarily reflected in the deadlocked inter-institutional negotiations on the reform of the Dublin Regulation revolving around the question of whether to replace the ‘state of first entry’ rule with a mandatory relocation mechanism to distribute asylum seekers across EU member states. These cleavages were exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic which further exposed serious flaws in EU migration governance as well as the EU’s limitations in the face of crisis.

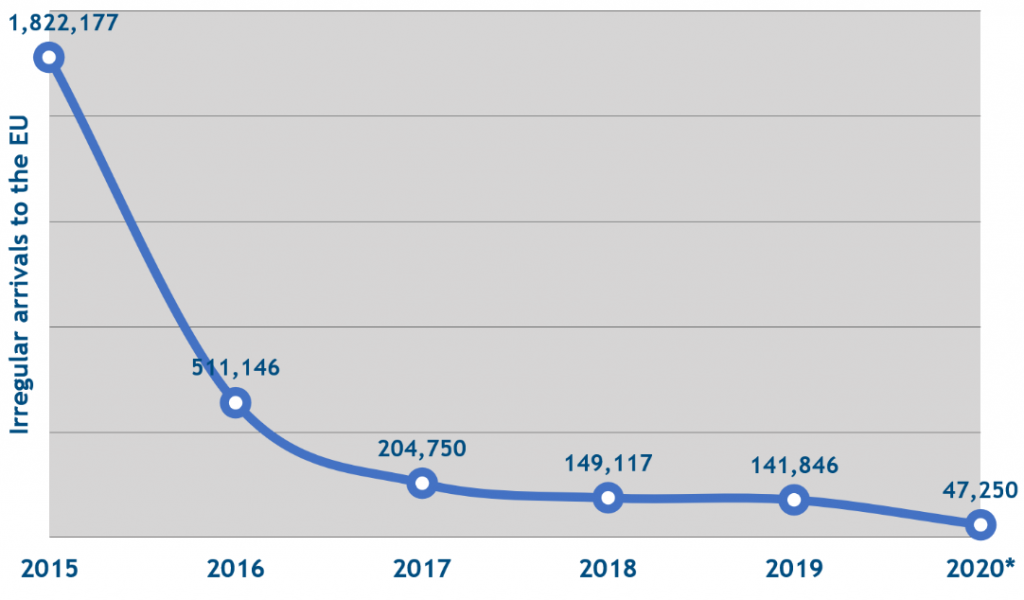

EU institutions and member states have similarly failed to overcome their differences and pull together in the spirit of solidarity during the pandemic. Even though, unlike the asymmetrical impact of the ‘refugee crisis’, the pandemic has affected all states bar none. Still, following the outbreak of Covid-19, divisions have grown deeper within the EU in terms of its approach to irregular migration, stemming from the fact that policymaking in this field continues to be dominated by national concerns. Accordingly, the pandemic has further strained intergovernmental relations in the EU. Against this backdrop, the EU remains as divided as ever in terms of its response to irregular migration, despite irregular arrivals to Europe decreasing in the aftermath of the 2015-17 crisis.

Figure 1: Detections of illegal border-crossings at the EU’s external borders (2015 to 31 July 2020)

Note: The figures for 2020 refer to the period until 31 July. Compiled by the author using data from the website of Frontex.

While the governance of migration in the EU is becoming increasingly fragmented, it is also becoming increasingly restrictive towards irregular migrants. In this regard, the pandemic has augmented the perceived threat of irregular migrants as they are being increasingly viewed as spreaders, resulting in the implementation of more restrictive migration measures in most EU member states. For instance, Italy and Malta have closed their ports to persons rescued at sea for the duration of the health emergency. Both governments later stated that migrants rescued in the Mediterranean would be quarantined at sea in order to prevent the spread of the virus, sparking criticism from NGOs advocating migrants’ rights.

Restrictive measures taken by other member states included reintroducing internal border controls within the Schengen Area to prevent irregular secondary movements of migrants from neighbouring states under the guise of protecting public health. Certain states, such as Austria, Denmark, France, Germany and Sweden, have had border checks in place since the outbreak of the previous crisis in 2015.

Given that the main migratory routes into the EU are across the Mediterranean, the southern EU members have been at the forefront in dealing with the issue of irregular migration and hence have assumed a much higher degree of asylum responsibility. Furthermore, due to their geographical proximity to main departure points for irregular migrants, they are disadvantaged by the Dublin rules, which in most cases assign asylum responsibility to the first EU state in which an asylum seeker arrives. Nonetheless, as in previous years, appeals for solidarity by the southern member states have largely fallen on deaf ears.

One such case in point is the Malta Declaration agreed upon by Italy and Malta together with France and Germany in September 2019 under the Finnish Presidency of the Council of the EU, whereby the five states declared their intent to develop a new scheme for disembarkation and relocation of migrants rescued at sea to ease pressure on Italy and Malta. The proposal, however, was rejected the following month by EU interior ministers in the Justice and Home Affairs Council.

The Covid-19 crisis is giving rise to a similar response from EU member states and the pursuit of national interests rather than common ones. More concretely, the pandemic has revealed the lack of solidarity and unity in the EU response to irregular migration even in an unprecedented situation.

Current European responses to irregular migration thus illustrate that the governance of migration is giving rise to suboptimal policy outcomes. In other words, the tightening of national migration policies has resulted in a ‘race to the bottom’ in asylum standards and rights across Europe. Moreover, the pandemic has exposed the unwillingness of EU leaders to act cohesively in the face of a major crisis. All of this increases the likelihood of the EU developing into an ‘ever looser’ Union, which could ultimately lead to the fragmentation of the European project.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Kripos_NCIS (CC BY-ND 2.0)

_________________________________

Nadia Petroni – University of Malta

Nadia Petroni – University of Malta

Nadia Petroni is a PhD Candidate in International Relations at the University of Malta. Her research interests focus on the diverse EU policy approaches to irregular migration and the resulting impact on EU asylum and migration policymaking.