Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine have all held elections in October and November. Clara Volintiru and Sergiu Gherghina write that while the elections broadly represented a success story for the EU’s efforts to promote democratic values in the region, they also showcased the continued importance of clientelistic practices in the three states.

This autumn has been election season in the Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries. Local elections in Ukraine, which began with a first round of voting on 25 October, were followed by presidential elections in Moldova on 1 and 15 November, where Maia Sandu defeated the incumbent pro-Russian President, Igor Dodon. Meanwhile in Georgia, two rounds of parliamentary elections were scheduled for 31 October and 21 November, resulting in a majority for the ruling Georgian Dream party.

The elections have provided important information about future dynamics in the region. Broadly, they have signalled the relative success of the EU in promoting democratic values in its strategic periphery, but this should not be regarded as an irreversible process and continued support for reform-oriented actors will be necessary.

Push and pull factors

In recent years, the EaP countries have gradually distanced themselves from a position of strong economic dependence on Russia and have increased their economic interactions with the EU. This has particularly been the case since Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine signed Association Agreements with the EU in 2014. The EU’s single market has effectively become the largest trading partner for these states. It accounts for half of total trade in the case of Moldova and Ukraine, and a quarter of total trade in the case of Georgia. Technical assistance programmes and transatlantic aid programmes are equally important pull factors.

Maia Sandu meeting with Donald Tusk in 2019, Credit: European Council

Members of the diaspora play a key role in the national economy of Moldova, where almost a third of the population currently lives and works abroad, by providing economic remittances. Maia Sandu stood in the recent presidential election on a pro-European, anti-corruption and anti-poverty platform, and support from the diaspora was vital to her success. Moldova’s turn to the West has been motivated in part by the lure of economic growth: the EU accounts for around 60% of Foreign Direct Investment in Moldova and has provided technical assistance programmes of almost 800 million euros over the past decade. If this constitutes the ‘pull’ factor then the ‘push’ factor stems from endemic corruption at the national level, which culminated in the theft of approximately 7% of the country’s GDP from its leading banks in 2014.

In Ukraine and Georgia, external financial assistance has followed a similar pattern. Approximately 1.5 billion euros have been allocated to Ukraine via EU technical assistance programmes. Much of this funding has had an electoral impact. The EU-assisted process of decentralisation that has been implemented in Ukraine, for instance, was an important contextual factor in the country’s recent local elections. Georgia, for its part, has received over 700 million euros in EU technical assistance programmes.

Political parties and clientelism

While civil society actors are important, it is domestic political actors that have the largest impact on institutional reform. It is especially at local and regional levels that efforts should be concentrated to prevent corruption and promote high standards. In a recent study, we tested the extent to which some of the most important political parties in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine engaged in informal practices such as clientelism, which further erode the rule of law in their countries.

Our study was based on data from an original expert survey that included a total of 171 experts (academics, representatives of civil society organisations and journalists) from each of the three countries. The research covered the main political parties that have been in power for the last decade, so did not include newer parties like Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s Servant of the People, or the Action and Solidarity Party of newly elected President Maia Sandu in Moldova.

Clientelism is a much broader phenomenon than corruption as it not only involves the use of public resources for private gains – a frequent practice in EaP countries – but also the consolidation of networks of loyal supporters who help secure electoral victories. It is also intrinsically linked to quality of governance, as poor performance in office can lead to a reliance on clientelistic exchanges.

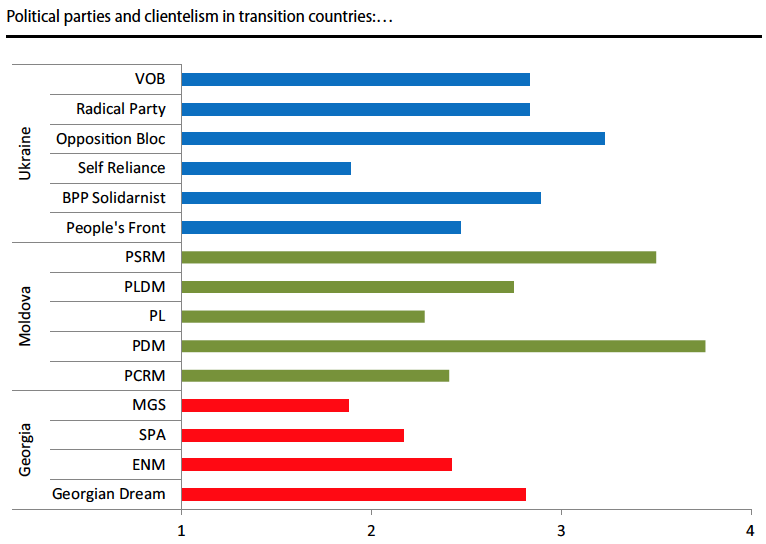

Our findings indicate that organisational characteristics of parties – territorial coverage and the reputations of local leaders – are a key driving force behind clientelism. Private funding is also an important source for clientelism, with parties engaging in the practice in Ukraine in particular. While these three variables play an important role in shaping the decisions of parties to use resources toward such goals, there are important differences between countries. We also found that in each of the three countries the exchange of goods and services for votes had different drivers. In Georgia, the reputation of local politicians mattered most. In Moldova, territorial coverage had the strongest effect, while in Ukraine the most important factors were private funding and poor performance in office. Our findings are illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: The extent of clientelistic practices by selected parties in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine according to expert survey responses

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Acta Politica.

There are variations between countries with many Moldovan and Ukrainian parties oriented more towards clientelism than those in Georgia. There is also great variation within the same country. The Ukrainian parties appear to form quite a homogenous group with regard to the extent to which they practice clientelism. Parties of leading figures in Ukrainian politics over the past decade – Yulia Timoshenko’s Fatherland (VOB), Petro Poroshenko’s European Solidarity (BPP Solidarnist) or the pro-Russian Opposition Bloc (now in different local splinters) – were all found to employ clientelism heavily to fuel electoral support.

In Moldova, the ruling party of the former president Igor Dodon (PSRM) and its coalition partner, the Democratic Party of Moldova (PDM) are considered to employ clientelism to the largest extent. Among the Georgian parties, both the governing Georgian Dream and the opposition United National Movement (ENM) use more clientelism compared to the other two parties included in the analysis.

Our study emphasises something important for politics in the eastern periphery of Europe: money is not enough to win an election, you also need roots in society. Failed attempts by local oligarchs have proven this point over recent years – from the demise of Vladimir Plahotniuc or the political struggles of Balti mayor Renato Usatii in Moldova, to Ihor Kolomoyskyi’s or Andriy Palchevskiy’s electoral failures in Ukraine.

Clientelism relies on both resources and networks and is extensively used by incumbents. Across the region, parties that do not seem to rely heavily on clientelism – such as the Self Reliance Party in Ukraine, the Party of Communists (PCRM) and the Liberal parties in Moldova, or Industry Will Save Georgia (MGS) in Georgia – have all experienced poor electoral performances in recent years. In short, resources matter more when they come from the public coffers, and particular attention should be devoted to the use of public spending both from within and outside the borders of these countries.

Finally, while clientelism is detrimental to democratic accountability, its capacity to mobilise supporters is not a silver bullet for incumbent parties. Reforms also matter, and without them clientelism can only achieve so much. For example, the survival in power of Georgian Dream during this year’s elections was partly built on extensive clientelistic linkages, which have secured the party a remarkable level of political stability. However, Georgian Dream has also been credited with the effective management of the Covid-19 pandemic and has pursued a steady path towards western integration. In contrast, Igor Dodon’s surprise defeat in the Moldovan presidential election came despite his party (the PSRM) displaying high levels of clientelism in our analysis.

Supporting the rule of law and democracy

Internal party politics is often muddled by electoral volatility, the clientelistic mobilisation of supporters, and ambiguous commitments to reforms. A better understanding of the actors on the ground is needed, at both national and local levels, to build better, stronger democratic alliances.

The EU’s commitment to promoting democracy and the rule of law in its strategic periphery is clearly outlined in a variety of financial instruments, and this approach is expected to continue in the coming years. Additionally, the US could and should become an equally important player in the region, with a new and enhanced international assistance agenda for democracy promotion.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council