The Netherlands will hold a general election on 17 March. Matthew E Bergman presents a comprehensive analysis of what the main parties’ manifestos indicate about the country’s current electoral dynamics.

Voters in the Netherlands head to the polls in just over a month. A childcare allowance scandal brought down the previous government and in recent weeks there have been protests over the imposition of a curfew as a Covid-19 mitigation measure. Despite this, the polls have stabilised. The People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), led by current Prime Minister Mark Rutte, is set to gain seats when compared to the last election in 2017. The opposition nationalist Party for Freedom (PVV), led by Geert Wilders, is also set to gain seats.

Issue diversity in the Dutch party system

After taking over as party leader in 2006 and serving one term in opposition, Rutte has helped establish the VVD as the most popular party in the Netherlands. Although the VVD sits with the liberals in the European parliament, political scientists place the party on the right side of the political spectrum on both economic and social issues. In 2012, Rutte formed a coalition with the Labour Party, then the nation’s second largest party. The 2017 election campaign, which was notable for the increasing salience of immigration, resulted in Wilders’ anti-immigration PVV taking second place. Since that election, the Dutch party system has been characterised by competition between the two largest parties, as well as five mid-sized parties and several smaller parties.

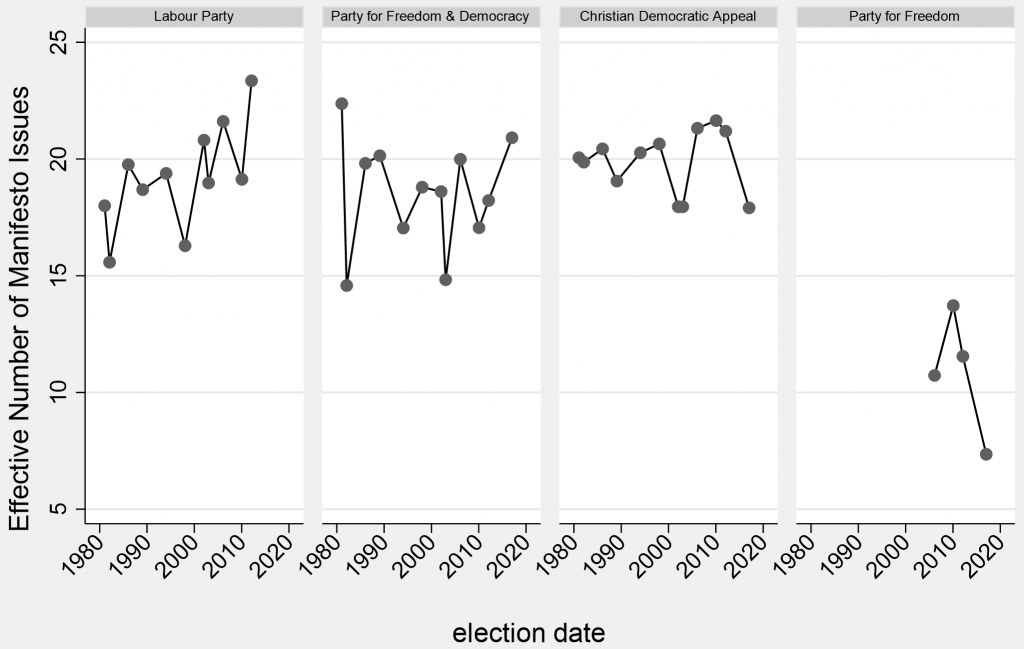

While several studies focus on the positions that parties take, my research focuses on the number and types of issues that parties campaign on. Typically, green, nationalist, ethno-regional and agrarian parties focus on only a few issues, which often leads to them being designated as ‘niche parties’. In contrast, mainstream parties such as social democratic, conservative, liberal and Christian democratic parties generally address a broad array of issues. Figure 1 uses comparative manifesto data to trace the number of issues (up to a maximum of 42) that the major Dutch parties have addressed in recent elections.

Figure 1: Number of issues contained in the manifestos of major Dutch parties (1980-2017)

Note: Graphs by CMP party code.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the Dutch case fits expectations about niche and mainstream parties. The nationalist Party for Freedom typically addresses only a small number of issues in its manifestos, particularly when compared with the mainstream parties. In fact, the party’s manifesto in 2017 was just one page long.

Previous research I have conducted with Henry Flatt demonstrates that nationalist parties with a focused agenda have much to gain from broadening the number of issues they discuss. If they were to discuss other conservative social issues, for instance, they could potentially gain votes from conservative parties. Alternatively, if they were to discuss economically centrist or leftist issues, they could potentially gain working class supporters. When broadening their agenda, nationalist parties are unlikely to lose their core nativist voters. On the other hand, if other niche parties, like green or ethno-regional parties begin to discuss other issues, their core supporters might accuse them of selling out.

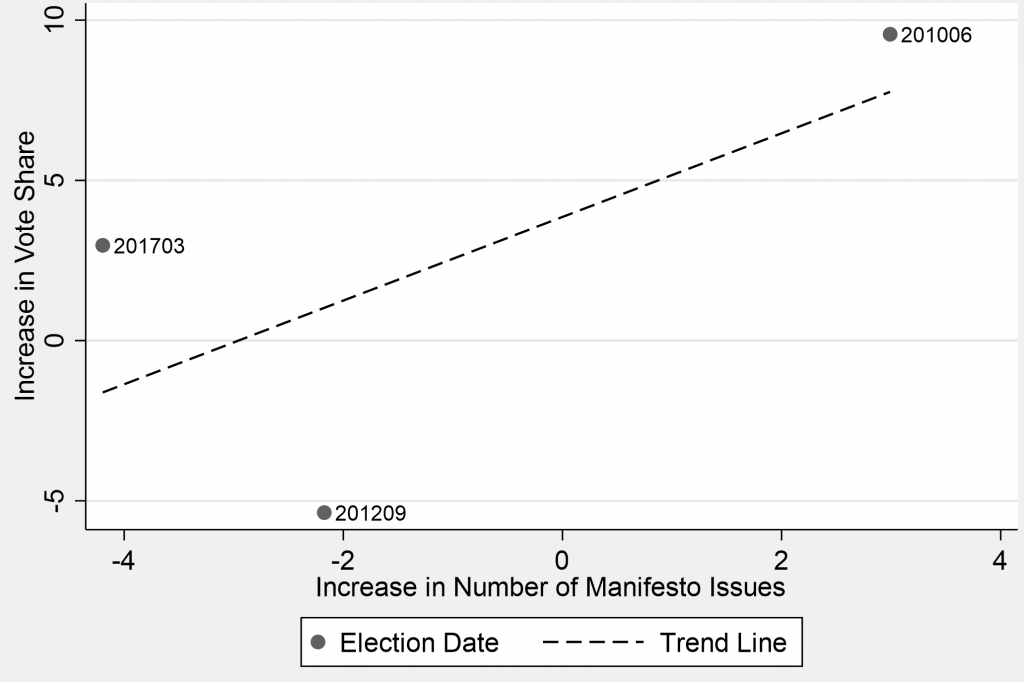

We substantiated these claims by analysing data from 206 elections across 23 countries. Figure 2 isolates the election dynamics of the Party for Freedom. Although the PVV has only participated in four elections, the party tends to gain more votes when it expands the number of issues it addresses. Given that 2017 represented a low point in terms of the breadth of issues addressed by the PVV, it has much political space to expand into.

Figure 2: Relationship between the Party for Freedom’s vote share and the number of issues contained in the party’s election manifestos

Note: The points shown in the figure indicate the dates of general elections held in the Netherlands.

In follow-up research, we performed a similar analysis with respect to mainstream parties. We argue that centre-left parties are cross-pressured when it comes to expanding the number of issues they address. If these parties focus on environmental issues, for instance, they may lose the support of voters more concerned about welfare state provisioning. If they address immigration issues, they may lose the support of core voters who are concerned about equality or progressive social causes.

The centre-right does not face this dilemma. Research has suggested that voters are likely to identify with the right if they hold either conservative economic or social positions, while identifying with the left requires both liberal economic and social positions. Centre-right parties can therefore gain votes by addressing new economic or social issues without fear of losing their core supporters.

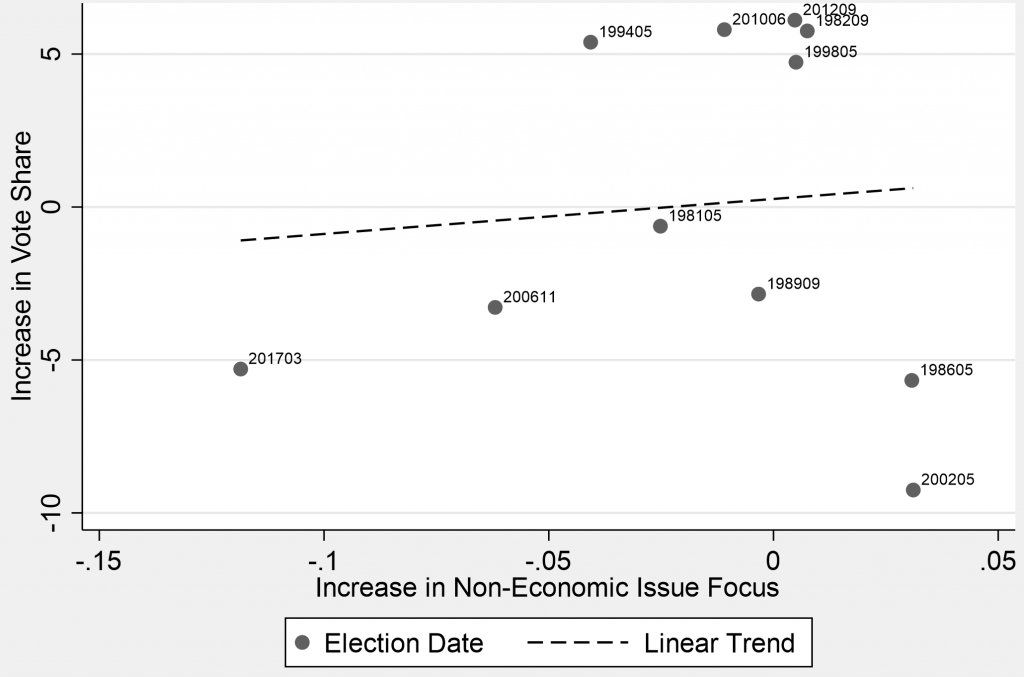

We verify this claim using the same 23 country dataset mentioned above. Figure 3 isolates the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy’s election dynamics. The VVD tends to increase its vote share when it places greater emphasis on non-economic issues (i.e. environmental, European Union, regional or nativist issues) in its campaigning. This was evident in 2017 when the party reduced its focus on non-economic issues and subsequently lost around 5% of the national vote share. Thus, the VVD also has room to expand its issue diversity.

Figure 3: Relationship between the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy’s vote share and the party’s focus on non-economic issues

Note: The points shown in the figure indicate the dates of general elections held in the Netherlands.

With its 2021 campaign manifesto, the VVD seems to be taking advantage of the privileged issue position that centre-right parties enjoy. The party is trying to attract socially conservative but economically centrist voters with a focus on the public sector, healthcare, increasing the minimum wage, and tax cuts for full-time workers. Unlike its 2017 strategy, the VVD has placed greater emphasis on non-economic issues including introducing environmentally conscious road pricing, a quota for refugees, and requiring immigrants to learn Dutch. Almost all polls suggest the VVD will gain seats this March.

As mentioned above, the PVV focused its campaign in 2017 on its core anti-immigration and anti-Islam platform. For the 2021 election, the PVV has outlined a fifty-page manifesto – a marked contrast to the single page it produced for the last election. While the new manifesto continues to focus on nationalist issues, the party has certainly broadened its agenda. Three pages are dedicated to climate issues, while centre-left economic issues also play a prominent role, with the party now advocating a rise in the minimum wage, as well as increased housing and assistance for the elderly, together with a reduction in medical fees and the retirement age.

The PVV has also stated that the three largest parties after the election should automatically enter into discussions to see if a coalition is possible. According to recent polling data, this is likely to be the centre-right VVD, nationalist PVV, and Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA). These three parties previously had a coalition agreement between 2010 and 2012, under which the VVD and CDA formed a government with support from the PVV. Should a three-party coalition be formed again, these are the only parties that are likely to win enough seats to do so.

The current government is a coalition of four parties led by the VVD. The other three parties are the CDA, the left-libertarian D66, and the smaller Christian Union party. Junior coalition partners tend to lose votes in subsequent elections as voters hold them accountable for failed promises. D66, for example, is polling lower than in 2017 – the party’s initial opposition to the Covid-19 curfew, which it subsequently rolled back on, is likely to be fresh in the minds of voters. On the other hand, the CDA, led by health minister Hugo de Jonge, has not suffered a drop in the polls. A majority of the Dutch population is supportive of the government’s approach to the pandemic and the CDA is now emphasising regional representation issues in its campaign.

If the incumbent centre-right parties’ broader appeals convince enough non-conservatives to vote their way (and if they agree again to cooperate), then another four-party coalition could form. If, however, the PVV convinces enough mainstream voters that they are best placed to tackle economic issues, then Wilders could block such a coalition from materialising, requiring negotiations between five parties to form a majority (something that has not been seen in the Netherlands for fifty years) or an agreement between the VVD, PVV and CDA.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council

What are the r^2 values for those regression lines? 0.1 and 0.2?