Much of the response to Mario Draghi’s appointment as Prime Minister of Italy has focused on the technocratic nature of his government. Martin J. Bull argues that while Draghi may be a technocrat, his programme is already generating a significant realignment within Italian politics.

The new Italian government, led by Mario Draghi, former President of the European Central Bank and Governor of the Bank of Italy, received resounding votes of confidence in both the Chamber of Deputies and Senate on 17-18 February. This technocrat with no parliamentary experience, has put together a government that includes eight technical ministers and has the support of all the political parties except one, the far right ‘Brothers of Italy’, which has opted to stay in opposition.

Draghi the technocrat

Much is being made of the technocratic nature of this government of ‘national unity’ whose origins lie in the collapse, in January, of the second government of Giuseppe Conte and the subsequent failure of the parties to form an alternative. In view of the urgent challenges facing Italy on various fronts, the Italian President, Sergio Mattarella, rather than dissolve parliament and call elections, opted for a Draghi solution to see Italy through to its next scheduled elections in March 2023.

Draghi laid out to the Senate a comprehensive set of goals related to managing the pandemic, expanding the roll-out of the vaccine programme and finalising the use of the huge recovery fund (financed by the EU), in addition to tax, environmental and judicial reforms, alongside other measures to try and protect employment. The sheer scale of this reform programme (which Draghi dubbed ‘New Reconstruction’, echoing the early post-war governments) and its timeline makes this technocratic government stand out from its predecessors (Ciampi, Dini, Monti), which have tended to be more narrowly reform-specific and time-limited. Furthermore, in stark contrast with the last technocratic government (of Mario Monti, 2011-13) where the main task was, on the back of the Great Recession, administering severe expenditure cuts, Draghi’s chief purpose is to work out how best to spend Italy’s share of the EU’s recovery fund, a staggering 203 billion euros.

The politics behind Draghi

All of this changes somewhat the apparent technical nature of this government. Draghi himself refuses to be pigeon-holed and says that his is simply ‘the government of the country’, rejecting the idea that he is there because of ‘the failure of politics’, and insisting that none of the parties should compromise on their identities. Yet, Draghi’s very appointment already appears to be having a momentous impact on the parties, and we could, in the coming period, witness a realignment of Italy’s political competition, a trend which already began with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Prior to the pandemic, that competition had been dominated by a rising anti-establishment, anti-EU, anti-migrant populism, in the form of both the Five Star Movement and Matteo Salvini’s League, both parties seeming to reap the benefits of a latent rebellion against a decade of austerity imposed by the EU and the mainstream parties.

The high-water mark of Italian populism came with the 2018 national elections and the coming to power of a Five Star/League coalition under Giuseppe Conte. While the Five Star Movement’s popularity waned during its period in office, the League’s support took off, and it walked out of the government in September 2019 in the hope of forcing elections and reaping the benefits. To avoid that outcome, Conte replaced the League with the Democratic Party to form his second government. The League adopted a position of intransigent opposition, and from there on the spectre of Italy’s largest party in the polls (the League polling ten percentage points higher than either of the two parties of government) hung over Conte’s fragile coalition.

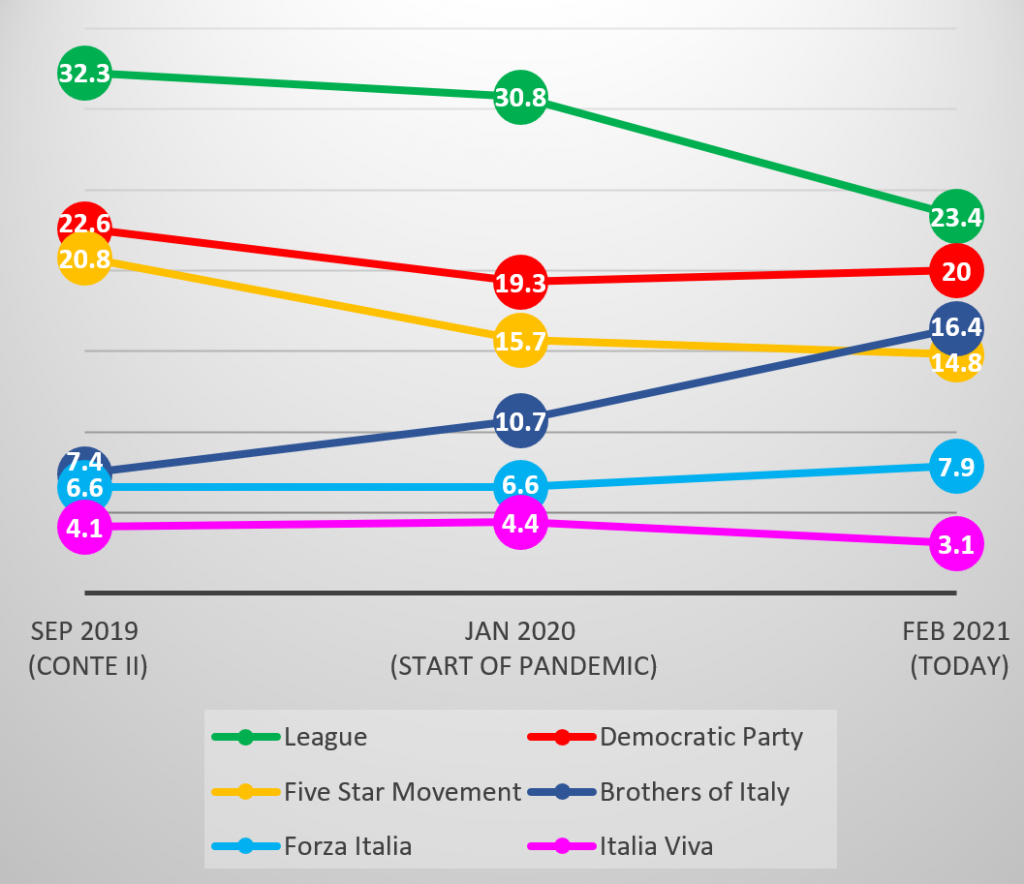

Figure 1: Support for the main Italian parties (2019-21)

Note: The chart illustrates how support for the main Italian parties has changed since the start of the second government led by Giuseppe Conte (September 2019) through the Covid-19 pandemic (January 2020) until today (February 2021). Source: Elaborated from ‘You Trend’ data.

The impact of the pandemic

Yet, all that changed with the pandemic. Despite the government confronting rather badly (in the first instance) the biggest public health crisis in peace-time Italy, the public rallied around Conte (the ‘lawyer of the people’), his personal ratings soared and support for the governing parties stabilised. The League meanwhile witnessed a steady slide in its support. Its anti-migration stance became redundant almost overnight as the flow of refugees stopped with the pandemic, and its anti-EU stance looked out of keeping once the EU forged a recovery fund from which Italy proportionately would be the largest recipient of all 27 nations.

Now today, the League is, with its former ally (the Five Star Movement), joining a government headed by the former Director of the European Central Bank, and we are hearing a different tune. Salvini argues that it is not the League that has changed its ideas, but Europe (in the sense of abandoning austerity and funding a real recovery programme). In reality, he wants to be around the table to influence decisions on how and when the funding should be spent. Yet, he may find it difficult to have his cake and eat it. When asked if he was now accepting the euro as inevitable, his retort was that the only thing inevitable in life was death. Draghi, in his speech to the Senate, pointedly made clear that, for anybody supporting his government, the euro was an ‘irreversible choice’.

End of a Eurosceptic era?

As nearly all the parties line up behind a European banker, where does that leave Italy’s renowned anti-establishment, anti-EU populism? Opposition to Draghi rests now with the right-wing Brothers of Italy, led by Giorgia Meloni. Yet, her opposition appears to be a more principled one, based on a rejection of technocrats to solve Italy’s problems. She is evidently hoping that, if things go badly for Draghi, the Brothers of Italy will reap the dividends and build further on their support, which has been rising during the pandemic.

Draghi, then, may be a technocrat brought in to design a programme of reform that sits above the parties. But his very appointment and his programme is already causing a significant realignment of the political forces behind him, bringing to an end Italy’s flirtation with ‘Italexit’, and laying the basis for a return of the country to its erstwhile position of being one of the most Europhile of all nations.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Presidenza della Repubblica (Public Domain)

Thanks Bully, that’s exactly what we want to hear, and what most of us hope is true. The country needs a move back to a more consensual centre and to stop behaving like cannibals at a bone fest.