Covid-19 has amplified the structural challenges that economies in Central Eastern and South Eastern Europe are facing. Áron Gereben and Patricia Wruuck write that the region needs to shift its approach to leave the threat of the middle-income trap behind and boost growth prospects in a post-pandemic world. Innovation, digitalisation, climate-change mitigation and a focus on skills should form the foundations for this new growth model.

The ‘old growth model’ of Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe, which drove convergence following EU accession, relied on exports, low labour costs, and capital inflows intermediated through foreign direct investment. This model has become less and less sustainable.

Productivity growth has slowed, while labour costs have increased. Lower capital inflows indicate the old growth model has reached its limits and it increasingly appears incapable of propelling the region’s convergence with the EU. In the absence of an alternative growth model, countries in the region may run the risk of getting stuck in the so called ‘middle-income trap’, where emerging markets that have experienced a rapid rise in growth nevertheless fall short of reaching the status of high-income economies.

We consider four elements to be key parts of a new growth engine for the economies of Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe. These four elements are domestic innovation as a key driver of productivity growth; investment in digitalisation; sustainable development toward a carbon-neutral economy; and the preservation and improvement of skills and human capital.

In a recent report, we examine the state of play in each of these four pillars, focusing on the private sector using firm-level data from the EIB Investment Survey (EIBIS). Based on this analysis, it is possible to address the challenges of transitioning towards the new growth model against the background of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Innovation

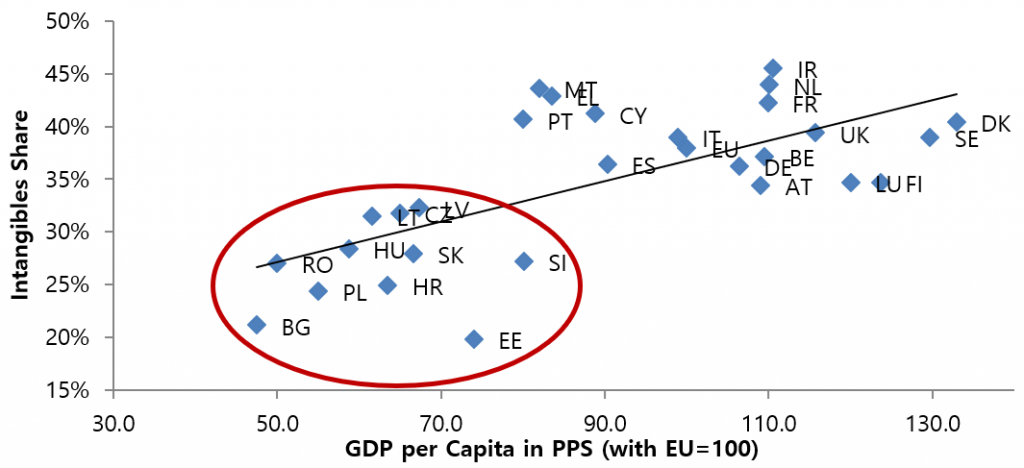

Technology adoption is still the main channel of improving productivity in the region, and domestic innovation plays only a minor role. Figure 1 illustrates the association between investment in knowledge and innovation – in the form of intangible assets – and the level of economic development. Innovation performance differs across different countries, however, as a group, the economies of Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe are still lagging behind the EU and innovation is happening mostly in large, foreign-owned manufacturing firms.

Figure 1: Correlation between GDP per capita and share of intangible investment in total corporate investment (2017)

Source: EIB Investment Survey, Eurostat

More private firms need to invest in intangible assets, particularly Research and Development, to translate research into innovation, strengthen innovation ecosystems and boost productivity. The key challenge remains reducing the share of firms neither actively advancing nor adopting innovation, which still amount to some 60% of the corporate sector.

The reasons behind this innovation gap include a lack of finance, as suggested by a study by the Vienna Initiative. Fostering capital market development and increasing the set of capital providers that are able to finance and support innovative companies is therefore key to supporting the innovation process. Beyond finance, limited availability of skilled labour often poses obstacles to innovative companies and start-ups. Strengthening the skill base is therefore a prerequisite for advancing the transition to a knowledge economy.

Digitalisation

Digitalisation reemphasises the case for investment in skills and human capital across the region. Digitalisation can contribute to innovation as an enabling factor. New technologies can also alleviate labour shortages. However, without adequate policy measures, it can add to the strains of the labour market by increasing skill mismatches and substituting workers with machines, thereby adding to social polarisation.

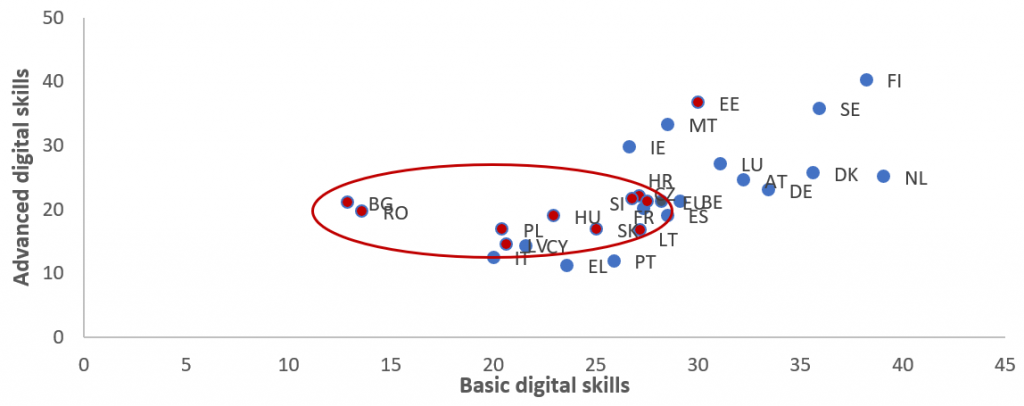

The development of basic digital skills is particularly important in determining the overall labour market impact of digitalisation as constraints in basic digital skills can skew firms’ investment in digital technologies towards the labour-saving type. While the region is home to advanced digital talent and skills in special areas, many countries are lagging behind in basic digital skills, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Basic versus advanced digital skills in EU countries

Note: The figure is based on the Digital Economy and Society Index published by the European Commission. The human capital dimension of the index measures ‘basic’ internet user skills (users with at least basic digital skills, above basic skills and basic software skills) and advanced digital skills and development (availability of ICT specialists and ICT graduates). The use of internet services scores are calculated as weighted averages of internet use, online activities and online transactions.

Policy support for digitalisation in the region is needed to strengthen both education and life-long learning systems, prioritising the acquisition of digital skills together with the acquisition of human-centric skills complementary to technologies. Initiatives focused on businesses should foster access to early stage funding and the creation of accelerators and incubators.

Green growth

As part of the EU’s agenda to achieve a net zero-carbon economy by 2050, the economies of Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe are shifting their energy systems and related infrastructure towards sustainability. Notwithstanding improvements in their carbon footprint over the last few decades, the energy intensity of these economies remains above the EU average.

However, the transformation towards carbon neutrality is bound to unlock new economic and business opportunities, for example in renewable energy production. Given the legacy of the region, strong policy action is needed to drive the transition and help mitigate possible adverse social impacts from the low carbon transformation. Yet, there are many ‘low hanging fruits’, as suggested in a study by the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership.

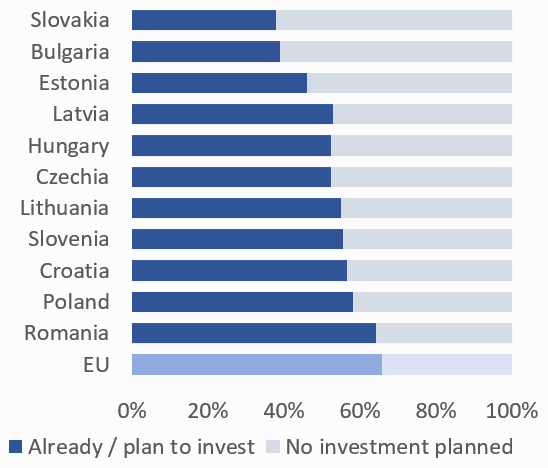

Figure 3: Share of firms with investment plans to tackle climate change impact

Source: EIB Investment Survey 2020

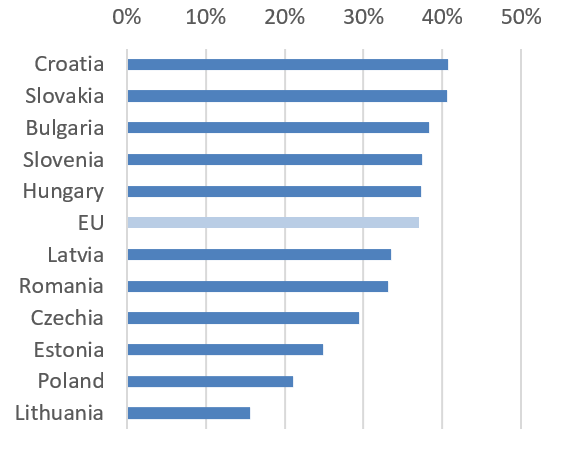

Figure 4: Average share of firms’ building stock meeting high energy efficiency standards

Source: EIB Investment Survey 2020

For instance, refurbishing buildings could reduce carbon emissions and improve quality of life. More innovative financing support is crucial to tap potential energy saving in the residential sector. Differentiated strategies, reflecting local geographical conditions, can help to strengthen renewable electricity generation. Transportation is another high impact area that could be targeted by upgrading pre-existing extensive public transportation systems and supporting accelerated electrification of the car fleet.

Skills – the key to the puzzle

Labour market shortages may temporarily ease due to the shock from the pandemic, but structural drivers, such as adverse demographics and emigration are likely to bring them back soon, adding to the risks to long-term growth. Active labour market policies can help ease shortages by improving job matching and bringing the inactive population to the job market. Moreover, they can help increase the availability of much-needed skillsets through support for reskilling and upskilling. Public financial support for job creation is also needed in the regions affected by the green and digital transitions.

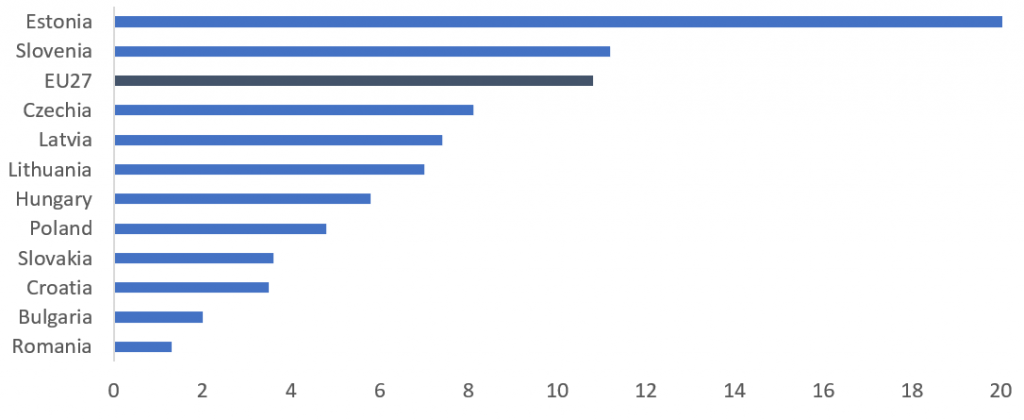

Figure 5: Share of the adult population participating in lifelong learning in 2019

Source: Eurostat

Central, Eastern and South Eastern European countries need to boost adult learning to deal with the pressures of digitalisation and decarbonisation on the labour market. Current participation remains low, as shown in Figure 5 above. Broadening firms’ investment into training is pivotal here, as many economies in the region have a high share of jobs at risk of being automated.

Boosting adult learning, including digital learning opportunities, needs to be combined with efforts to strengthen quality and inclusiveness in education. Beyond technical skillsets, strengthening the focus on communication, creativity, critical thinking and leadership skills should be prioritised, together with policies that foster inclusiveness to mitigate risks of early detachment from the labour market.

Strengthening the four elements of this new growth model together would bring benefits to citizens in the region. The goals of increasing innovation, digitalisation, making growth more sustainable and expanding skills are closely intertwined. While innovation is increasingly digital, the technologies (to be) developed can power a successful green transition. Skills underpin these processes and enable individuals to seize the opportunities of economic transformation.

The shock from Covid-19 has amplified the structural challenges the economies of Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe are facing. Lockdowns have demonstrated the critical importance of digitalisation for competitiveness and economic resilience. Moreover, they have showed that alternative, sustainable ways of working are possible. At the same time, the pandemic may result in the widening of inequalities and societal fault lines if the impact is not adequately addressed and countries in the region are slow to embrace structural transformations.

Recovery strategies centred on the four elements of this new growth model can lead to robust and sustainable growth, but leaving the bottlenecks unaddressed could jeopardise longer-term competitiveness. National recovery plans to set out key public investment projects and reforms should reflect these considerations.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying Working Paper published by the European Investment Bank

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Sushobhan Badhai on Unsplash