The Covid-19 pandemic is a global crisis, but it has had a highly varied impact on different regions across Europe. Marta Angelici, Paolo Berta, Joan Costa-Font and Gilberto Turati argue that while centralised decision-making can help solve collective action problems like border closures, the management of the response to a health emergency is often more effective when it is implemented at the local level. They highlight that decentralised health care governance helps explain why mortality rates were lower in Italy than in Spain during the first wave of the pandemic.

Issues of territorial governance have been at the centre of policy responses to new virus outbreaks in the past, such as the emergence of Sars in 2002, the Mers outbreak in 2012, and the Ebola outbreak in 2013. The balance of power between a highly centralised form of governance and more decentralised solutions has played a central role in these cases.

Although the fight against Covid-19 is a global one that requires coordination at the highest possible level – for which Europe is still not prepared – crucial local knowledge about how best to address the challenges posed by a pandemic might not be used when decision-making is completely centralised. This is of particular relevance in many healthcare systems in the European Union where health policy takes place at different levels of government. While coordination across borders is required at a Europe-wide level to face the pandemic, regional reactions might respond better to idiosyncratic needs; hence, a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach might not always be the most efficient solution, especially when the impact of policies is highly uncertain, as in the presence of a completely new virus.

Centralised governance entails a uniform response to counteract adverse effects of territorial self-interest (e.g., not sharing timely information, or circulating essential protective equipment). In contrast, advocates of decentralisation put forward the role of innovation and low-cost experimentation when the optimal policy reaction is unknown, such as when a new virus is surrounded by uncertainty.

Decentralised governance can still allow for some degree of coordination, for instance via pandemic plans within and even between countries. Coordination via these plans allows for a swift exchange of information on the characteristics of the pathogen, alongside the set-up of common standards to track its evolution and collect comparable data, and regulations to manage the actions of infected patients and prevent the spread of the disease further (including border closures and quarantines).

In the UK, the Coronavirus Act 2020 conferred new powers on devolved ministers. This has allowed devolved administrations to make new regulations to tackle the pandemic. Although reactions were originally similar across the UK, Scotland and Wales have implemented different policies with regards to restrictions on movement. The Scottish government has even introduced additional legislation, the Coronavirus (Scotland) Act. However, coordination has also taken place, with the first ministers of the different countries participating in meetings of the Civil Contingencies Committee chaired by the prime minister. The main outstanding quarrels have been around the implementation of the tier system and funding across regions.

Comparing Italy and Spain

In a recent study, we compare the national and sub-national reactions to Covid-19 in Italy and Spain during the first wave of the outbreak, when countries had to decide what to do rapidly to protect the health of their citizens with almost no information on the potential impact of specific policies.

Italy and Spain share common institutional backgrounds, including decentralised health care systems, but they each differed in the governance of the first wave of the pandemic. While the Spanish government centralised the purchase of health care equipment and imposed coordination at the central level, the Italian government did not enforce full coordination among the regional governments. As such, a comparison of the two countries helps inform the discussion surrounding the optimal balance between a highly centralised and a more decentralised solution.

Central level coordination can amplify the effect of a policy when it succeeds but also when it fails. Hence, if a uniform response across an entire national territory is not the most effective, the country as a whole will suffer. In contrast, experimentation might be important when countries are in search of an optimal solution. If regional governments can identify their own policy solutions to tackle the virus, which prove effective, then other regions can adopt the same solutions and the negative consequences of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ policy are avoided. This is precisely what occurred in the Veneto Region in Italy. Despite bordering the Lombardy Region, Veneto experienced fewer than 20,000 cases in comparison to the roughly 80,000 cases in Lombardy during the first wave of the pandemic.

Cross country differences

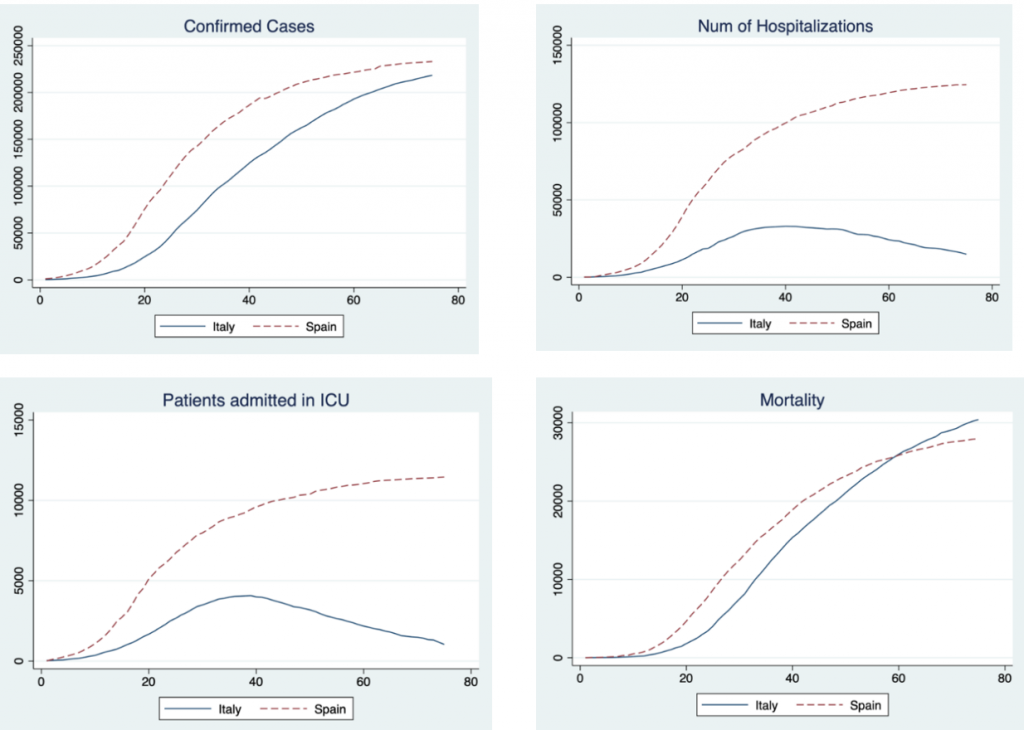

Figure 1 displays the cross-country comparisons. The figures reveal a consistent picture: despite Spain having a population of about 47 million people compared to the roughly 60 million people in Italy, Spain recorded a higher number of confirmed cases, hospitalised patients, patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) and deaths, although the Italian curve crosses the Spanish one at the end of the period analysed here. More strikingly, whilst hospitalisations and admissions to ICUs tail-off after 30 days in Italy, they continue growing in Spain.

Figure 1: The first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in Italy and Spain

Note: The figures cover a period of 75 days corresponding to the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. The time series for each country is paired based on the date at which they both exhibited the same number of hospitalised patients: the starting point for Italy is 25 February 2020 and the starting point for Spain is 7 March 2020.

The key conclusion from this analysis is that decentralised government offers an advantage when responding to a pandemic. More specifically, we document a significant gap in the trends in cases, hospital and ICU admissions, and mortality in Italy and Spain, both at the national and at the regional level. Our analysis indicates that the strong localisation of the pandemic in Italy and the existence of regional autonomy explain the differences between the two countries.

Coordination does play a role in solving potential collective action problems such as border closures. However, our evidence indicates that regional autonomy, via experimentation and local knowledge, can make a difference in the number of lives saved, as well as in avoiding unnecessary hospitalisations. The experience of the UK also suggests that regional autonomy is not at odds with coordination.

A system that encourages regional cooperation, but that relies on regional autonomy, might therefore be beneficial for meeting the challenges posed by pandemics. This approach allows for the emergence of good practices compared to more centralised approaches, especially when regional needs and knowledge are largely heterogeneous. This lesson was ultimately learned in Spain, as in the later waves of the pandemic the country did not pursue such a centralised response, which helped improve health and social care outcomes.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying working paper

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Ministero Difesa (CC BY-NC 2.0)