The decision to go to university can have a major impact on an individual’s financial future and quality of life. Yet we know relatively little about how these decisions are made and adapted within different contexts. Drawing on a new study of East German students following German reunification, Ghazala Azmat and Katja M. Kaufmann show how the education plans of young people are shaped by their environment.

Whether to go to university or not is an important decision with fundamental long-term implications. Higher educational attainment has consequences for individuals’ later economic success and general well-being and, from a more macro perspective it is the key to understanding the emergence, development and persistence of inequality. Young people make college plans and shape human capital investments accordingly. Yet despite the importance of these decisions, little is known about this process – what influences educational plans and whether (and how fast) they adapt to a changing environment.

Individual decisions are generally made in the context of specific sets of social norms, rules, values and worldviews. A central challenge to measuring university plans is that the environment in which these plans are formed and adjusted is co-determined with the individuals’ characteristics. This makes it difficult to disentangle the effect of the environment on outcomes. In a new study, we overcome this challenge by exploiting a large shock to the environment to estimate the impact on the university plans of adolescents and to understand which factors determine these plans and how they are adjusted as a result of a shock.

German reunification

We use the ‘quasi-experiment’ of German reunification in October 1990 to study the impact on the educational plans of young people in East Germany. The fall of the Berlin Wall marked a period of profound change that swept through Eastern Europe. East Germany, instead of experiencing a change of government within its borders or newfound independence, as did other countries in this area, transitioned from a socialist system with a planned economy to the democratic-capitalistic system of West Germany.

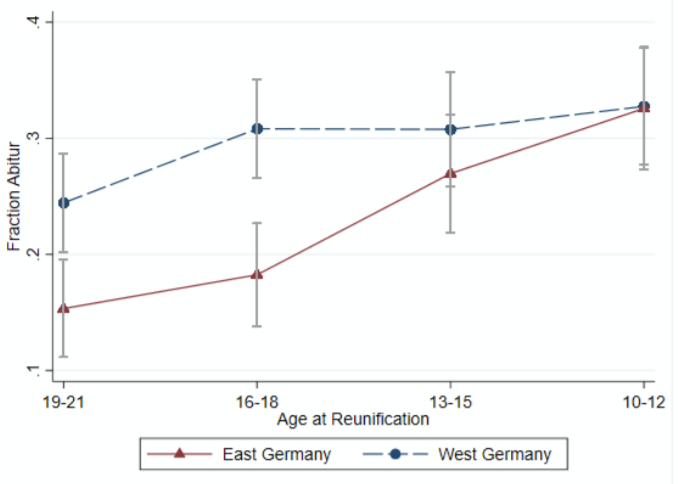

What impact did this have on young people? Looking at Figure 1, we see that the long-standing educational gap in completion of the ‘Abitur’ (the certificate that is a prerequisite for entering university) between East and West Germany closed entirely approximately one decade after reunification.

Figure 1: Abitur completion rates in East and West Germany

Note: The figure displays Abitur completion rates (college entrance certificate) for different cohorts of youths in East and West Germany. The dots represent the average fraction of individuals that completed the Abitur for different cohorts (by age at reunification) and the grey bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

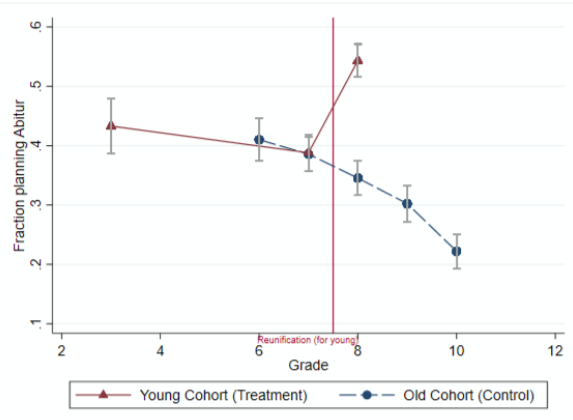

Using detailed annual-longitudinal data on different cohorts of East German students, we can see that the switch in regime induced an immediate and sharp increase in university plans, which, several years later, indeed translated almost entirely into an actual increase in going to university among these youths. Students are repeatedly asked about their education plans and, in particular, whether they plan to undertake the Abitur. Figure 2 plots – across different academic years (grades) – the means and confidence intervals of education plans of two cohorts of students.

Figure 2: The effect of reunification on Abitur plans in East Germany

Note: The figure displays Abitur plans for a ‘young’ and an ‘old’ cohort in East Germany and how they evolve across grades. The dots represent the average fraction of youths planning to obtain the Abitur and the grey bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

We focus on the plans of the ‘younger’ cohort, aged 13 at the time of reunification, and compare them to the evolution of plans of an ‘older’ cohort over the same grades (before reunification). The older cohort serve as a counterfactual trend for what would have happened to university plans between the same grades without reunification. Superimposing, by academic grade, the education plans of the older cohort on those of the younger cohort shows that in the pre-reunification period, there is no significant difference in the level nor in the development of Abitur plans. However, reunification induced a large structural break in plans. The likelihood of undertaking the Abitur increased by 22% for the younger cohort.

Expected returns, preferences, and the adjustment process

What drove this change in education plans? A standard education model tells us that there are three main factors that determine education decisions: expected (monetary) returns, preferences for education, and constraints. Data on each component is usually not readily available, which makes it difficult to understand the importance of the different factors and how adaptable they are to changing circumstances. In our study, however, we can separately analyse these factors to examine the mechanism behind our main findings. Investigating the motives behind the change in young people’s plans, we show that a leading explanation is that, even at a young age, adolescents understood that the economic implications of going to university changed and they reacted to this.

The German reunification implied a sizeable increase in the returns to education for East Germans. For instance, previous research by Alberto Alesina and Nicola Fuchs-Schündeln has shown the average net income of individuals with a university degree in the East was only 15% higher than that of a blue-collar worker, compared to 70% in the West. We show that reunification did indeed increase students’ expected returns from education and this change happened soon after reunification. When we link this change to university plans, we see that plans increased the most among those whose perceived returns increased more.

Turning to economic, social and political preferences, some important changes followed reunification. Most notably, students became more ‘individualistic’ and converged in their preferences with those of the West. Moreover, the individuals whose preferences adjusted the most are those who updated their university plans the most. There is a growing body of literature that seeks to understand the role of culture in preference formation and while these values are likely to persist, they can adapt to a new status quo, especially at certain formative ages.

In fact, when we explore the role of the age (or educational stage) at which individuals are affected by a macro shock, we see that it is key. Slightly older individuals who were closer to a critical education juncture at the time of reunification adjusted their plans to a much lesser extent than the younger cohort, consistent with the fact that they exhibited a slower adjustment in their preferences, while they updated expected returns from education in the same way.

From a policy perspective, it has been well established that early investments in children are critical for long-run economic success. Our research helps to uncover the link between early education planning and later education decisions and outcomes, offering insights into the black box of the education decision process. It is crucial to understand the role played by beliefs of the labour market; how education plans depend on family background, skills, beliefs, preferences and constraints; the malleability of plans and whether they can adjust to new circumstances.

For more information, see the authors’ CEP discussion paper Formation of College Plans: Expected Returns, Preferences, and Adjustment Process

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Redd on Unsplash