The SPD’s victory in the German federal election on 26 September would have seemed unthinkable in the early stages of the campaign, with the party languishing in the polls. Yet as Mark A. Kayser, Arndt Leininger and Anastasiia Vlasenko write, the result was only partially surprising for election forecasters. Drawing on the outcome of the election, they illustrate why structural models for predicting a party’s long-term electoral potential often do a better job than analyses based on opinion polling.

The 2021 German federal election on 26 September was unprecedented in many ways. For instance, it was the first time in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany, which knows no term limits, that an incumbent chancellor was not running for re-election. It was also the first time three parties – the ruling Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU), the German Social Democrats (SPD), and the Greens – fielded candidates for the chancellorship. And, of course, it was the first time that voters were called to vote nationally after the Covid-19 pandemic had hit Germany.

The results saw the SPD beat outgoing chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU, with the Greens coming in a distant third place. A few weeks earlier, hardly anyone would have expected such an outcome as both the CDU and the Greens were polling well ahead of the SPD. However, scientific election forecasters were only partially surprised.

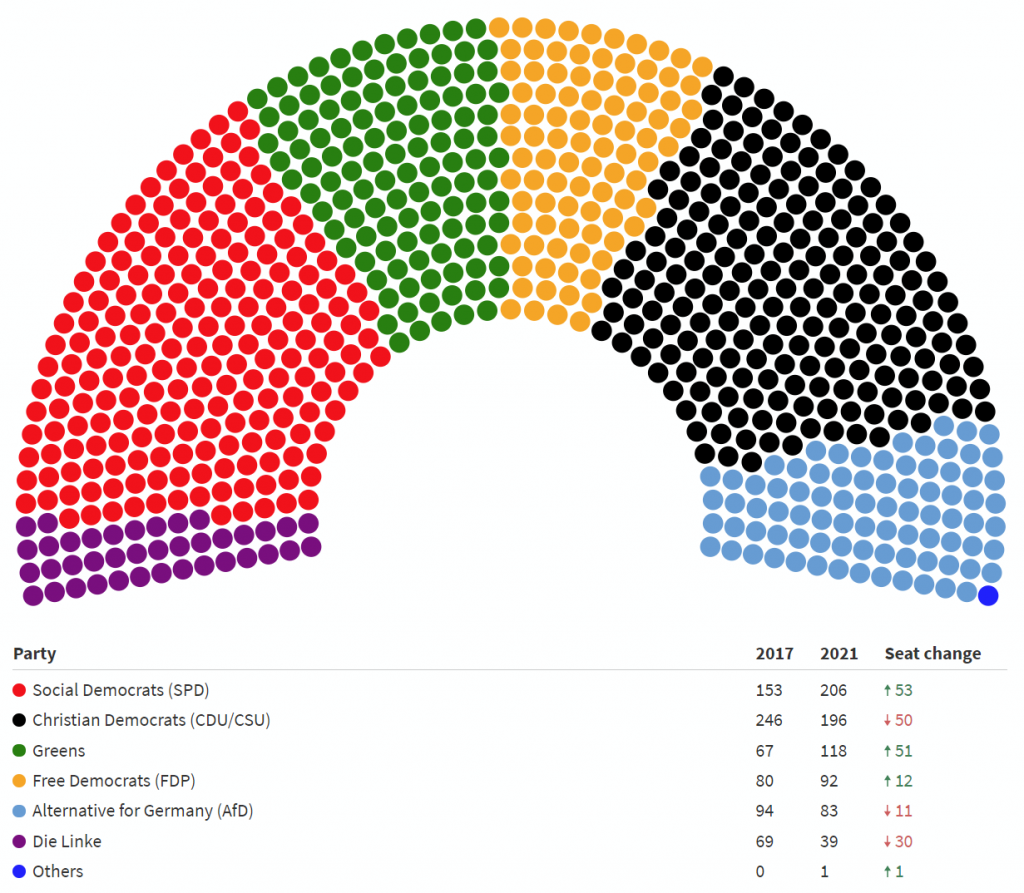

Figure 1: Provisional seat totals in the 2021 German federal election

Note: Figure created with Flourish. Data source: Bundeswahlleiter

When the parties first nominated their candidates – between August 2020 and April 2020 – several teams of political scientists were busy preparing their forecasting models and papers for submission to a symposium aimed at predicting the outcome of the election. We were among the six teams. We estimated and submitted our forecast in late June of this year. Like a number of other authors in the symposium, we developed a so-called structural model.

The specific design of a structural model derives from the theories and empirical findings from electoral studies. Following the so-called Michigan model of electoral decision-making, many election forecasting models take into account a mixture of short- (for example, the economic situation in the quarter before the election), medium- (for example, the popularity of the country’s leader), and long-term factors (for example, past election results).

Our ‘Länder-based model’, which we developed for and first applied to the 2017 German national election, was based on a dataset of election results for the six major parties in all 16 German states in all national elections since 1961. Using a statistical model, we estimated the relationship between national election outcomes, past national election outcomes, outcomes of mid-term elections in Germany’s federal states, the state of the economy, and government tenure and extrapolated into the future. Our model derives its name from the fact that we incorporated election returns from elections in Germany’s 16 states (Länder in German).

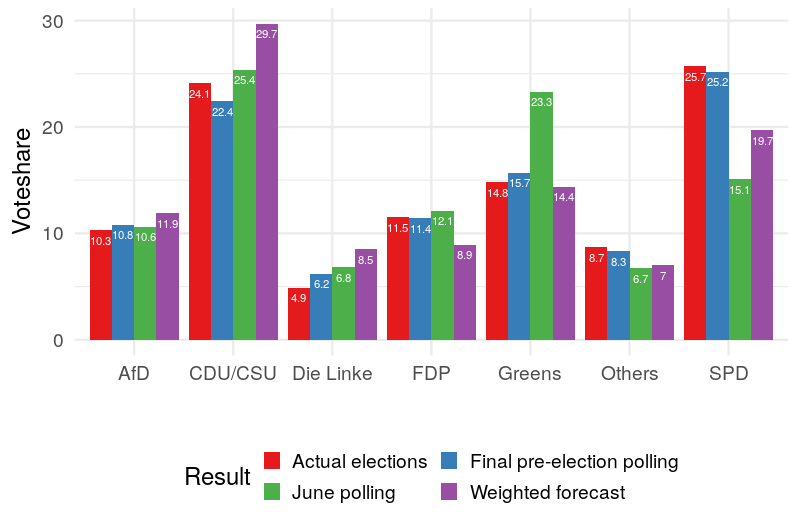

Figure 2: Election result, polling projections and structural model forecast

Note: Compiled by the authors.

Using our model, which does not require polling data, we were able to issue a forecast of the election outcome in June, well before the parties’ campaigns went into full swing. With our forecast of 14.3% for the Greens, who were still above 20% in the polls at the time, we were pretty close to their final result of 14.8%. For the SPD, we predicted 19.7% at a time when the party was still polling at 15.9%. Hence, we at least partially anticipated the party’s upward trend.

However, as did all other forecasts, we ended up missing the outcome for the CDU/CSU. Its election result of 24.1% was considerably lower than the 29.9% we predicted. We also overestimated Die Linke (a forecast of 8.4% vs. 4.9% in the election) and slightly underestimated the FDP (8.9% vs 11.5%). Our forecast for the far-right AfD and the residual category ‘others’, incorporating parties that failed to clear Germany’s 5% electoral threshold, were on point.

One can view this as a mixed result. However, we should highlight that our forecast, just as in 2017, represented a more accurate prediction of the election outcome than those based on vote intention polls conducted at the time we issued our forecast. In 2017, we issued our forecast in March of the election year and also beat polls conducted at that time in terms of accuracy – we were only a percentage point less accurate than the final pre-election polls in September 2017.

Why forecasting models work

If populations in established democracies are becoming ever more diverse and electorates ever more volatile, as indicated by a secular decline in party identification, how can a forecast calculated months ahead of the election be almost as accurate as final pre-election polls?

Andrew Gelman and Gary King addressed this question in a seminal paper on election predictions in the United States. In the paper, they argued that forecasting models work not despite but because of the election campaigns. Election campaigns provide voters with information on the so-called fundamentals that many election forecasting models such as ours rely on. This includes the state of the economy or the competence of the head of government.

As campaigns progress and citizens gather more information, polls become more informative of actual voting behaviour in the election. In contrast, vote intention polls are a relatively poor predictor of actual behaviour when the election is still far away and few respondents are thinking about politics. Hence, there is also a more general lesson to be drawn for voters and the media, namely that prediction models are not only better predictors when the election to be forecast is still far away, but that they, unlike polls, are also actual forecasts.

Furthermore, it should be noted that forecasting models such as ours can still be useful even if they are sometimes off the mark. Structural models perform the vital function of setting expectations against which actual election outcomes can eventually be compared. Election forecasting models basically predict how an average candidate with an average campaign and opposition will do in the election. Thus, forecasts help us identify what is extraordinary about an individual election.

Hence, our forecast bears important lessons for the political parties. For one, the CDU must admit that it has fallen far short of its electoral potential. Our forecast and all other forecasts in the symposium we contributed to predicted that the party should have obtained at least 29% of the vote.

In contrast, the SPD can take credit for having exceeded its long-term voter potential, thanks in part to its campaign, which successfully portrayed their candidate Olaf Scholz as the rightful heir to Angela Merkel, and someone who is capable of delivering the stability that Germans so desire. The party outperformed all forecasts.

In contrast, the Greens should come to realise that mid-term vote intention polls might reflect the current political mood but are not realistic estimates of their electoral potential. Of course, their campaign, which was perceived by many as weak and error-prone, might not have helped them either.

However, this is now their third disappointing election in a row after 2013 and 2017, in which they underperformed relative to poll results weeks and months before the election. These good mid-term polls for the Greens in recent years reflect societal change: climate change has become an important issue for many citizens and the Greens are less demonised by the conservative media and political opponents. But this does not mean that they could obtain these numbers at an actual election.

Hence, a second conclusion flowing from forecasting models of the German federal election is that they represent better estimates of a party’s long-term electoral potential than vote intention polls.

For more information, see the accompanying symposium published by PS: Political Science & Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council