The decline of social democratic parties in Western Europe has received substantial academic attention, but there remains little consensus on how these parties might reverse their electoral fortunes. Drawing on a new study, Matt Polacko argues that in an age of rising inequality, social democrats stand to benefit from shifting to the left on the economy.

The SPD’s victory in the 2021 German federal election notwithstanding, the decline of social democratic parties has been one of the most important trends in European politics over the last few decades. Much of the associated debate has revolved around these parties’ rightward policy shifts, which have allegedly turned social democrats away from their founding principle of equality in an age of increasing inequality.

In a recent study, I find income inequality to be a key mechanism moderating social democratic policy offerings and their support. Based on data from 22 countries between 1965 and 2019, my analysis shows that when social democratic parties shift to the right on the economy, they experience a lower vote share under higher levels of income inequality or when this shift is combined with rightward socio-cultural positions. These findings provide an important explanation for the party family’s pronounced electoral decline.

Inequality and support for social democratic parties

Social democratic parties tend to benefit if welfare state issues are salient during electoral campaigns. Despite this advantage, analyses of party manifestos confirm a gradual movement of social democrats towards the ideological centre through the abandonment of many traditional leftist positions.

The key elements in this transition have been these parties embracing the market, increased financialisation, privatisation, and deregulation, as well as reductions in tax and the welfare state. The result is that social democratic parties have become much less egalitarian during a period of rising inequality. Initially, this ‘Third Way’ party strategy seemed to bring strong electoral benefits in the late 1990s and early 2000s. However, social democratic parties across Europe have since witnessed a substantial decline in their vote shares as many traditional supporters have increasingly embraced challenger parties.

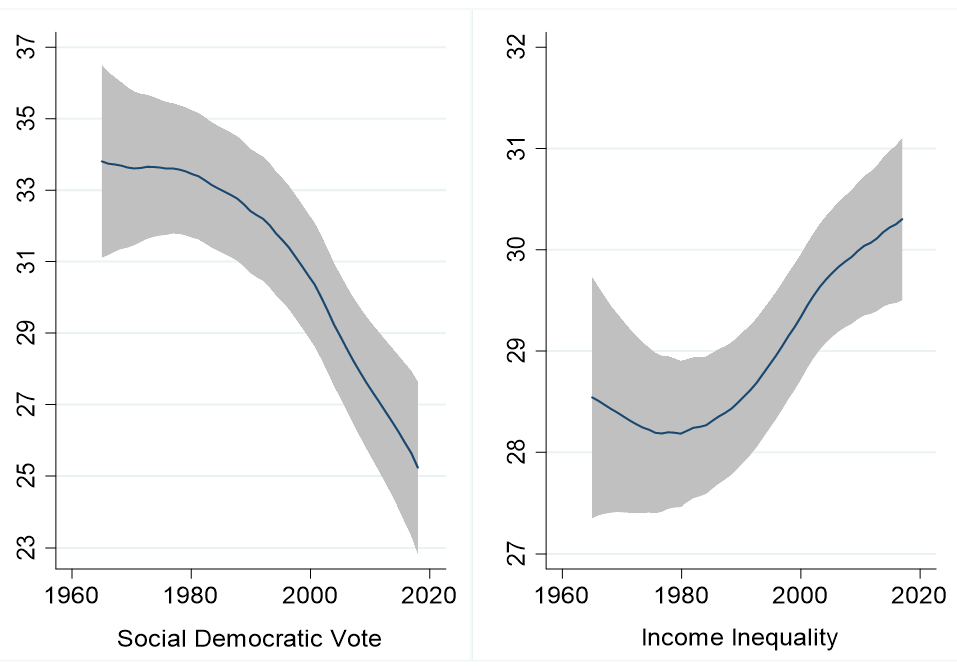

Figure 1 (left) illustrates this trend by plotting the combined vote share of 22 social democratic parties since 1965. The vote share for these parties held steady until the 1980s at roughly 34 percent, but then began to decline before falling dramatically from 31 to 25 percent in recent years. Correspondingly, income inequality (Figure 1 right) has risen by nearly 10 percent since the 1980s.

Figure 1: Trends in support for social democratic parties and income inequality

Note: The figure shows local polynomial smoothing of the vote share for social democratic parties (left) and the Gini index (right) between 1965 and 2019.

According to conflict theory, social democrats should benefit electorally from rising inequality, but in both individual- and aggregate level analyses, I find that they only do so if they offer clear leftist economic positions as party supply needs to meet citizen demand.

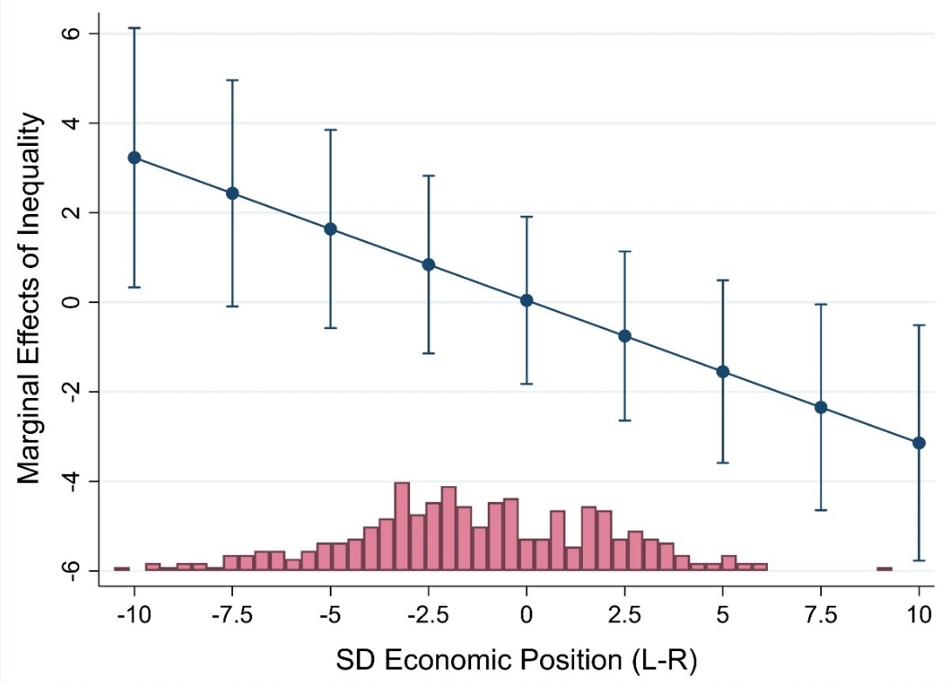

Figure 2 displays the average marginal effects of an interaction between inequality and the economic positions of social democratic parties on the vote share for these parties at the aggregate level. It shows that the effect of inequality is positive when social democratic parties are economically leftist and that their vote share is substantially dampened the more economically right-wing the parties become. In substantive terms, when standardised one deviation, the average marginal effect of inequality is associated with a roughly 1.5 percentage point increase in social democratic vote shares at a left-wing position, and a 0.5 percentage point decrease at a right-wing position.

Figure 2: Relationship between inequality, the economic positions of social democratic parties, and the vote shares for these parties

Note: The chart shows average marginal effects of inequality by the economic positions of social democratic parties on the vote share for these parties with 95% confidence intervals.

Additionally, the populist far-right has made substantial inroads among the working-class base of social democrats in recent years, which some believe is occurring because voters are increasingly being mobilised via identity rather than distributive politics. This has prompted a heated debate as to whether social democrats would reap electoral gains if they offered more restrictive immigration policies by pursuing a so-called accommodation strategy. I test for this using Comparative Manifesto Project (MARPOR) data, but do not find evidence that it is a winning strategy for social democrats. Nor is moving leftwards on the social-cultural dimension alone. However, I do find that adopting socio-cultural rightwards positions is substantially detrimental to social democrats when combined with rightward economic positions.

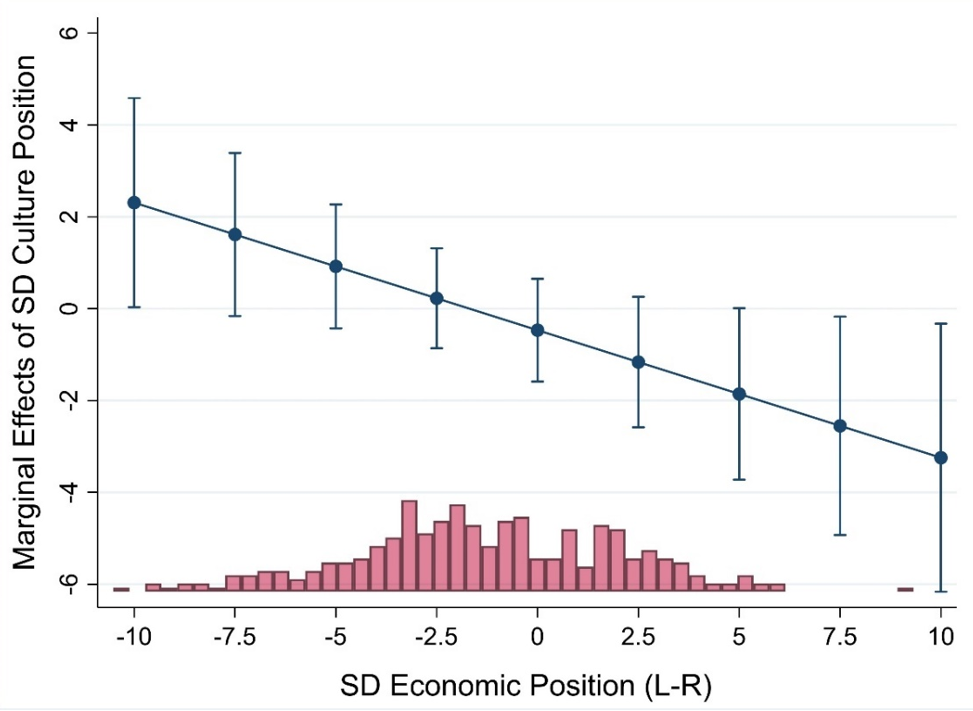

Figure 3 provides an illustration by displaying the average marginal effects of an interaction between the socio-cultural position of social democratic parties and their economic position on the vote share for these parties. It shows that the effect is roughly zero when social democrats are at their economic and socio-cultural mean. However, there is a significantly positive effect when the parties are left-wing on both dimensions and their vote share is dampened the more right-wing the parties become on both dimensions. In substantive terms, when standardised one deviation, the average marginal effect of a leftist socio-cultural position is associated with a roughly 1 percentage point increase in vote share, and a 1 percentage point decrease at a right-wing position.

Figure 3: Relationship between inequality, the socio-cultural positions of social democratic parties, and the vote shares for these parties

Note: The chart shows average marginal effects of inequality by the socio-cultural positions of social democratic parties on the vote share for these parties with 95% confidence intervals.

These findings have notable ramifications for party strategy. The rightward shift of social democratic parties has diluted the party family’s distinctive historical profile and left social democrats unable to fully take advantage of increased discontent stemming from the financial crisis, austerity, and rising inequality. Consequently, as voters are unable to spot much differentiation in the mainstream parties economically, political competition has moved to socio-cultural issues where parties on the right have an advantage.

My findings also shed light on why so many of the working class have abandoned social democratic parties. When social democrats shift rightward on redistribution, they alienate both their traditional base and much of the middle class and subsequently lose support. Labour market precarity and unemployment have spread into the higher skilled middle class and flexibilisation stemming from the deregulation of non-standard employment has created downward wage pressure among low- and middle-income insiders while benefitting top earners.

The brand dilution suffered by social democratic parties from engaging in reforms that conflict with the party family’s traditional image as protectors of the welfare state does not seem to have been counteracted by gains made from progressive movement on the socio-cultural dimension. Attempts to cultivate an image of economic and fiscal responsibility by moving to the right have also failed to compensate for the loss of traditional supporters.

Current polling suggests there is substantial support in West European countries for left-wing economic policies. Meanwhile, rising income inequality shows no sign of slowing and has only become more salient during the pandemic. Even if social democratic parties are only interested in stemming their own electoral decline, there is reason to believe they may benefit substantially from offering voters more redistributive policies. For example, recent elections in Norway and Germany where social democrats moved left on the economy (in Germany the SPD’s most leftist in decades), returned both parties from the political wilderness back into power.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying open access paper in West European Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: PES Communications (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)