Over the last decade, the economist Guy Standing has written on the emergence of a new class of citizens – the ‘precariat’ – who lack economic security and stable occupational identities. But can the concept of precarity also help explain the success of populist parties? Drawing on a new study, Lorenza Antonucci, Carlo D’Ippoliti, Laszlo Horvath and André Krouwel assess how precarity affects support for populist parties in France and the Netherlands.

Since 2016, scholars have been discussing the economic and cultural origins behind the rise of populist and radical voting in Europe – the so-called ‘Brexit effect’. A popular idea in this debate has been the suggestion that labour market insecurity generates support for anti-system politics.

However, labour market insecurity has been operationalised in limited ways, often looking at specific types of contracts (short-term/part-time) and without including multidimensional measures of insecurity. To advance the debate, we transpose the sociological notion of precarity popularised by Guy Standing to populist voting. This allows us to expand our understanding of populist voters beyond the ‘left behind’ to capture the insecure ‘squeezed middle’ which faces declining work and living conditions.

Our team has been working since 2016 to create a multidimensional understanding of precarity in voting research. Our contribution is both theoretical and empirical: we wanted to translate a sociological concept into political voting by creating new survey measures of precarity, identify different potential dimensions within the broad definition of precarity, and test whether precarity can explain voting. We ran a first test of our precarity indicators in France and the Netherlands during their national elections in 2017.

Our findings do show a positive association between electoral support for radical populist parties of the right and left and precarity in the two countries – as well as a negative association between precarity and voting for the traditional parties (Christian democrats and social democratic parties). Our work also highlights that one overlooked aspect of precarity is particularly relevant for explaining voting: the subjective insecurity of work conditions (precarity at work). Before moving to the findings, it is worth discussing how we expanded the measurement of precarity in voting.

Creating ‘precarity items’ in political research

The first step was to construct a comprehensive measure of precarity that fully reflects the multidimensionality of this concept. In addition to survey questions measuring the perceived likelihood to be dismissed, we introduce new measures of precarity from the job quality literature that had not been used before in relation to voting. You can find more information on the origins of these dimensions in our accompanying paper, which is available open access. These are able to capture new elements of precarity such as autonomy at work, satisfaction with job advancement, work-life balance, and cognitive employment insecurity, among others.

It is essential to include this multidimensional understanding of precarity: the sociology of work literature shows that, especially after the euro crisis, quality of work is the most diffused issue in European labour markets, even over the diffusion of tenure precarity (i.e. the spread of temporary contracts), which still affects a relative minority of workers. By including more items, we were able to explore the insecurity experienced by individuals that are generally assumed to be secure (the so-called labour market insiders), thereby expanding our understanding of populist voting by the ‘losers’ of globalisation.

Through exploratory factor analysis we extracted two main factors that denote the two distinct dimensions of precarity: a dimension called ‘precarity at work’ grouping items about subjective insecurity in working conditions; and a dimension that we identified as ‘precarity of tenure’ as it groups items measuring insecurity in the tenure of work. Table 1 contains a list of items and the two dimensions.

Table 1: Items for each dimension of precarity

Why would precarity be associated with populist voting? Relying on previous work by Noam Gidron and Peter A. Hall, we assume that two types of mechanisms lie behind this dynamic. An instrumental mechanism for which voters pull out from parties that have supported flexible labour market policies (Christian democrats and social democrats) and pull in to support radical populist right parties and radical left parties. Radical populist right parties have adopted a political agenda of welfare nativist statism that directly speaks to voters’ work insecurity, while radical left parties propose to address insecurity through changes that reverse the trend of ‘flexibilisation’ that has occurred over previous decades.

However, we don’t presuppose that this process is purely the product of full rational decision-making by voters: as highlighted by Gidron and Hall, there is also a symbolic process that makes voters move towards anti-establishment options in the presence of heightened insecurity.

The association between precarity and voting for the populist right and the radical left

Data collection was conducted shortly before and during the legislative elections held in the Netherlands and in France, consisting of 31,800 and 6,992 observations. Our findings show a relationship between precarity and voting for radical parties, but the effect varies across the two countries and depends on the specific dimension of precarity (tenure or precarity at work) and the type of radical support (radical populist right or radical left).

Firstly, in both countries precarity is associated with voting for radical populist parties (the Front National in France and Partij voor de Vrijheid in the Netherlands) and radical left parties (such as La France insoumise in France and the Socialistische Partij in the Netherlands). Our findings also show that voting for the two parties of the establishment (centre-right and centre-left) is negatively associated with precarity in both France and the Netherlands; the same negative effect is true for the newcomer in France, La République En Marche, which is aligned with a flexible labour market agenda.

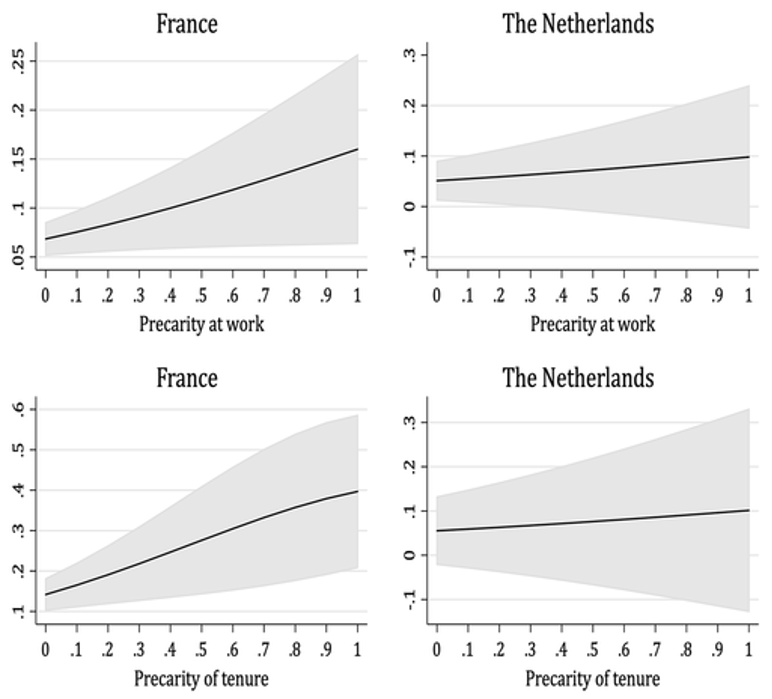

Figure 1: Estimated marginal impact of precarity at work and precarity of tenure on the probability of voting for radical populist right parties in France and the Netherlands

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Sociological Research Online.

Secondly, analysing the results by type of precarity and by type of radical support, precarity at work has effects on the odds of voting for both the radical populist right (Figure 1) and the radical left (Figure 2). In both countries the odds increase by a factor of two to three.

Precarity of tenure increases the odds of voting for the radical right in particular. This effect is particularly pronounced in France, where precarity of tenure increases the odds of voting for the radical right by a factor of 7.5. We interpret the relative higher importance of precarity at work over precarity of tenure in explaining voting in the two countries as an indication that issues of quality at work are widespread in both countries.

Figure 2: Estimated marginal impact of precarity at work and precarity of tenure on the probability of voting for radical left parties in France and the Netherlands

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Sociological Research Online.

These findings reveal that the policy trend of flexibilisation – and the related declining quality of work experienced by workers in France and the Netherlands – has political effects. In our framework, both radical populist right parties and radical left parties are able to attract the increasing subjective insecurity experienced by voters indirectly (framing themselves as anti-establishment) or directly through their agendas – with radical left parties proposing an anti-austerity solution to labour market insecurity and radical populist right parties proposing a form of chauvinist labour market protection for citizens.

Even if temporary contracts may still affect a minority of workers, insecurity of work conditions is a mainstream issue in European labour markets. This means that the precarity of work conditions could also potentially explain populist voting in other European countries. Future European-wide comparative studies could clarify this puzzle.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Sociological Research Online

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Benjamin Davies on Unsplash