Refugee populations are rarely a perfect representation of the makeup of the country they have fled from. This is because refugees are often ‘self-selected’ in the sense that certain types of people are more likely to choose to leave or to have the opportunities to do so. Drawing on new survey evidence, Judith Kohlenberger, Konrad Pędziwiatr, Bernhard Rengs, Bernhard Riederer, Ingrid Setz, Isabella Buber-Ennser, Jan Brzozowski and Olena Nahorniuk provide a detailed overview of the key characteristics of Ukrainian refugees in Austria and Poland.

As of July 2022, almost six million Ukrainians, predominantly women, children, and elderly people, had fled the ongoing war to European host countries. Neighbouring countries like Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary, but also Western European countries like Germany and Austria, have accepted thousands of refugees and are providing shelter, as well as access to healthcare, labour markets, and education. Poland is currently hosting around 2.2 million Ukrainian refugees. Some 69% of these refugees live in the twelve biggest Polish cities. Numbers in Austria are smaller, with roughly 72,000 registered Ukrainian refugees by mid-June 2022, the majority being located in the country’s capital Vienna.

In order to coordinate both integration and potential return assistance, government agencies, humanitarian organisations, and civil society need reliable data on those individuals who have left Ukraine. Early insights from online surveys and qualitative interviews suggest high self-selection among Ukrainian refugees in Europe. Two large surveys conducted simultaneously between April and June in Kraków (Poland) and Vienna (Austria) now provide additional insights. This data was collected in numerous locations where Ukrainian refugees assemble to register, arrange documents, or receive help in Kraków, and at the official arrival centre of the City of Vienna.

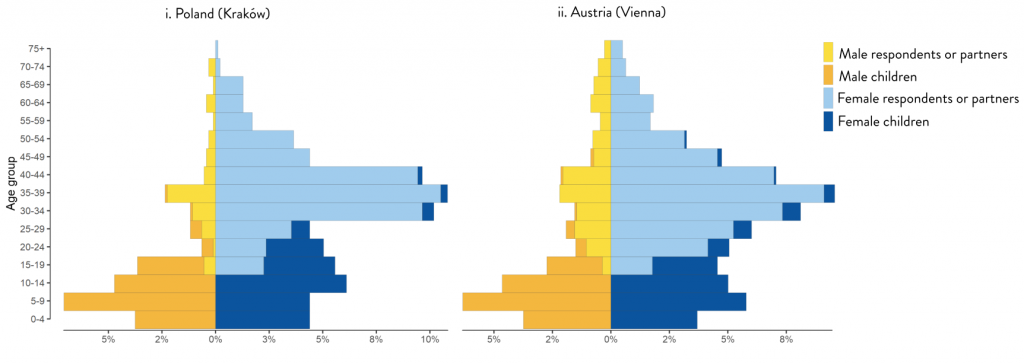

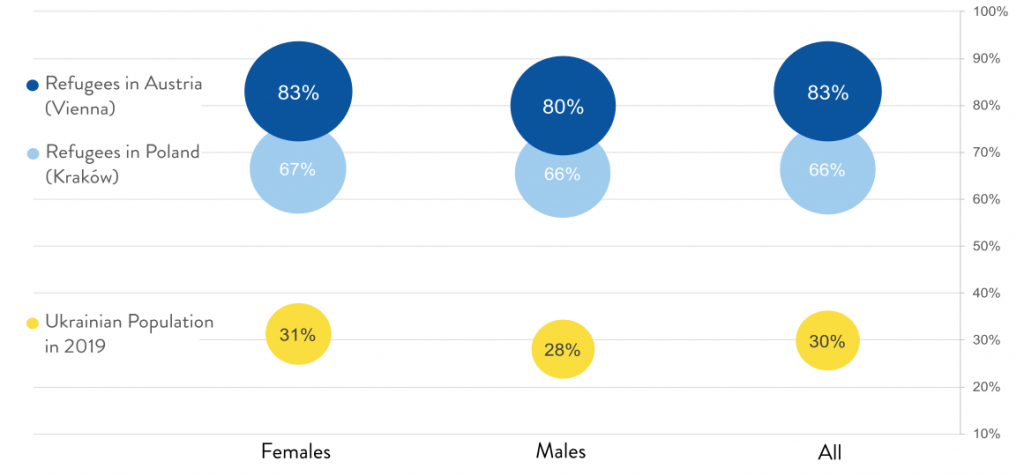

In terms of demographics, Ukrainian refugees substantially differ from the pre-war population of Ukraine. They are disproportionally female and in young or middle adulthood or children (Figure 1). The share of women arriving with their partners was much higher in Austria than in Poland by an unexpectedly high margin. Self-selection seems more pronounced with increasing distance from the home country. The share of tertiary educated is much higher among respondents in Austria than in Poland. In 2019, among the Ukrainian population aged 25 years and older, the share of those holding a bachelor’s degree or higher tertiary education was 30%. Among surveyed Ukrainian refugees and partners, this share amounts to 66% in Kraków and 83% in Vienna.

Figure 1: Age pyramid of Ukrainian refugees in Kraków and Vienna

Note: Age pyramids include children in Poland/Austria.

For Western European host countries, the inflow of highly educated refugees means that rapid recognition of academic degrees will be key for preventing stark mismatches between refugees’ qualifications and the jobs they end up working in. As de-qualification has been shown to be even more pronounced for women, the predominantly female refugee population from Ukraine should be supported with free childcare, on-the-job training, and flexible working hours, including a continuation of pandemic-related remote work.

Figure 2: Share of tertiary educated among male and female Ukrainian refugees aged 25+ in Kraków and Vienna

Note: Figure includes respondents as well as their partners if they stayed with them in Poland/Austria. Source of figures: State Statistics Service of Ukraine (2019). Social and demographic characteristics of households of Ukraine. Kyiv.

Echoing their high educational attainment, two thirds of responding refugees in Austria and one third in Poland report to speak English. Therefore, employers will need to display flexibility in recruiting well-qualified refugees who may not (yet) speak the language of the host country, but can adequately communicate in English. In light of the comprehensive labour shortage faced by many European countries, especially in elderly care, tourism, and catering, benefits will outweigh investments down the road.

A distinct picture also emerges regarding the socioeconomic status of refugee populations. While 30% of Ukrainian refugees in the Viennese survey are from Kyiv, the share is only roughly half of that in the Kraków sample. Conversely, the share of refugees who came from the Kharkiv, Dnipro, and Donetsk regions is larger in the Polish than in the Austrian sample. The fact that more than half of refugees in Austria consider themselves upper class or upper middle class again indicates self-selection.

The high degree of self-selection is also reflected by the refugees’ reasons for their choice of host country. Those who travelled farther than neighbouring countries could often rely on personal and professional networks for support. For Ukrainians moving to Austria, networks of friends, acquaintances, and colleagues (42% vs 16% respectively in Poland) were more relevant than family abroad (22%). Accordingly, incorporating existing diaspora communities in relief and integration efforts for Ukrainian newcomers should be part of Western European countries’ response to refugee inflows. The community effect for initial orientation and successful job searches for newly arrived refugees could be substantial.

Further reasons for choosing Austria as a host country include high quality of life, a well-functioning welfare state and support structures, previous stays as tourists or students, as well as German language skills. This degree of familiarity is unusual in the context of European host countries, where previous cohorts of refugees from the Middle East or the Global South, while still self-selected in terms of education and social status, displayed much less knowledge and active choice in terms of picking their host country. For policymakers and state agencies, active choice and familiarity can become assets for facilitating integration into host societies.

In accordance with their socioeconomic background, a high percentage of refugees in the Austrian sample are at least temporarily able to rent an apartment or rooms (60%). By comparison, a larger share of refugees in Poland live in private homes provided by Polish citizens (33%). This may constitute a challenge for Polish society in terms of durable voluntary support with accommodation. State subsidies for renting apartments and rooms going directly to refugees and not to Polish families for hosting them may became necessary. Additionally, subsidies may have to be extended beyond 120 days in view of an aggravating housing situation due to the decreasing availability of collective accommodation, such as dorms to which students will soon return from their summer break.

While long-term housing options will be crucial for some, a sizeable share of refugees (34%) in the Kraków sample state that they fled to Poland because of its proximity to Ukraine since they intend to return as soon as the war is over, despite feeling very welcome. Return intentions are less pronounced for those who travelled to Austria. In this group, roughly half plan to stay in the host country for the time being and a quarter are even unsure if they will return after the war. Some have no intention to return at all (7% in Poland, 8% in Austria).

This differentiated picture corroborates the OECD’s recommendation to implement dual intent policies. Ideally, Ukrainian refugees will receive support measures that assist with both integration in the host country and potential return and re-integration efforts in Ukraine. This appears intuitive for issues of employment and qualification, as research shows that long periods of unemployment lead to a lasting deterioration of refugees’ human capital and motivation, which may also affect the home country once return is possible.

The existing evidence suggests a highly self-selective migration from Ukraine to Europe has taken place, with implications for labour market integration in host countries. The farther Ukrainian refugees moved to the West, the higher their socioeconomic background, and the likelier their permanent re-settlement.

Active choice of and familiarity with the host country are largely unique to the Ukrainian displacement, whereas reliance on community networks and dependence on financial and social resources constitute well-documented effects of refugees’ self-selection into Europe. Host countries should be aware of these specifics and may want to adapt their integration policies accordingly, taking into account socioeconomic composition, intentions to return, and familiarity with the host society.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Konrad Pędziwiatr

Wouldn’t a better comparison be between Vienna and Warsaw, rather between the former city and Krakow? If someone is highly skilled, there would seem to intuitively be a greater chance they would head to the host country’s economically dominant city. That is unquestionably Warsaw in Poland, as it is equally unquestionably Vienna in Austria. One might guess that the correlations found in the study are influenced at least as much by the mismatch between a secondary and primary economic centre as they are by how far west a city happens to be.