Fratelli d’Italia emerged as the clear winner from Italy’s general election, but what explains the party’s success? Giovanni de Ghantuz Cubbe highlights the key factors that led to the result.

Fratelli d’Italia’s victory in the 2022 Italian general election was long predicted, however the key factors that produced the result remain uncertain. Although comprehensive statistical data and precise analyses of voting determinants are not yet available, a number of potential explanations can nevertheless be put forward.

First, the fact that Fratelli d’Italia was the only one of Italy’s main parties to remain in the opposition group during Mario Draghi’s government undoubtedly played a role in its success. This allowed the party to present itself as the only viable alternative, even at the expense of its ally, the League (Lega).

The League’s leader, Matteo Salvini, claimed as much at the end of the campaign, noting that Fratelli d’Italia had better ‘starting conditions’ compared to his own party, which as a government partner was ‘forced’ to cooperate and compromise with other political players. This was admittedly something of a convenient line for Salvini as it offered a ready-made excuse for his party’s declining support.

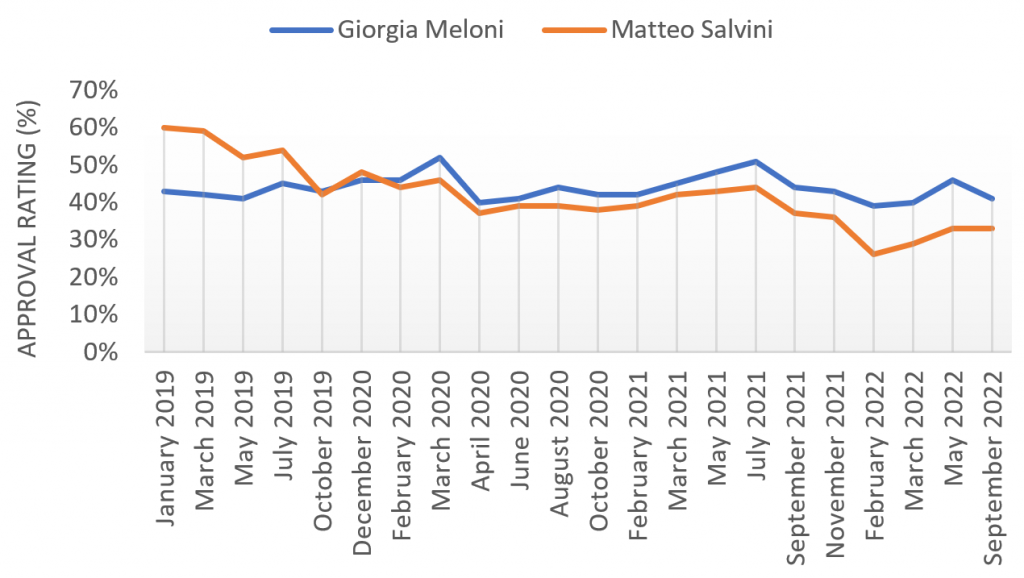

Second, the success of Fratelli d’Italia can be attributed to the popularity of its leader, Giorgia Meloni, who has been upstaging Salvini since the end of 2019. Figure 1 below illustrates this trend, which only became more pronounced during the leadup to the election. A few days before the election, 41% of Italians gave a positive rating to Meloni, while only 33% approved of Salvini.

Figure 1: Approval ratings for Giorgia Meloni and Matteo Salvini

Note: Compiled by the author using data from Demos & Pi.

Third, it is possible that Fratelli d’Italia successfully convinced parts of the Italian electorate that it has the capacity to get Italy’s economy back on track and that it can address the concerns of families and firms who are currently at risk from the energy crisis.

Using rhetoric that is typical of the League, Meloni presented herself as a defender of the less well-off. It is significant that just a few days before the election, some 93% of the party’s voters listed “the strengthening of financial support for families in difficulty” as a priority the new government should pursue (all other options in this poll fell under 90%).

One can also assume there is a link between the success of Fratelli d’Italia and the anti-immigration attitudes of a share of Italian voters. An example concerns the arrivals of immigrants and asylum-seekers via the Mediterranean route: in August this year, 53% of Italians agreed with turning back rescue boats at the border, while 46% wanted to take them in. Fratelli d’Italia and Lega voters were overrepresented in the former group. However, the role of the immigration issue, in contrast to 2018, should not be exaggerated. A few weeks before the election, only 5% of Italians mentioned immigration as one of the two most important challenges facing the country.

Finally, Fratelli d’Italia’s victory can be situated within a broader populist resurgence in Italy over the last decade, which is linked to long-term-causes. The rising importance of Italy’s ‘many populisms’ in 2013 (Five Star Movement), 2018 (the League) and 2022 (Fratelli d’Italia) is closely related to four factors: the weakness of Italy’s traditional parties; their ‘resignation’ in favour of technical (Mario Monti in 2011) and semi-technical governments (Mario Draghi in 2021); the general instability of the party system; and the ‘endless transition’ that it has experienced since the 1990s.

In short, Italian populists have been able to present themselves as a political alternative capable of addressing the deep structural weaknesses of the country. However, the extent to which they classify as a real alternative is debatable. They are in fact both a product and catalyst of the country’s structural malaise.

Finally, it cannot be ruled out that the success of Fratelli d’Italia indicates a genuine ideological shift of the Italian electorate to the right. While suggestions the election result represents a return to fascism are entirely overblown, the growing general acceptance by the public of political actors who have flirted with fascist rhetoric and symbolism is undoubtedly concerning.

Future scenarios

The new government will have the potential to bring about important changes both within Italy and with respect to the country’s relations with Europe. Much will depend on the government formation process that will take place in the coming days and weeks. A decisive factor will be whether the coalition chooses to present itself as a centre-right government or instead gives more space to the ideas of the radical right.

The internal stability of the coalition will also play a central role. We will soon find out whether Matteo Salvini is willing to accept his position as a subordinate ally of Meloni and what price he will demand in return. The more solid the governing majority is, the more extensive its future measures could be. It remains to be seen whether Meloni will try to implement the ‘sea blockade’ she announced during the campaign, but we may see a revival of Salvini’s ‘security decrees’ and other measures concerning refugee and migration policy.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Niccolò Chiamori on Unsplash