Modern Turkey was built on the foundations of the Ottoman Empire, but how has this legacy shaped Turkish economic development? Drawing on new research, Michael Cottakis and Gözde Yilmaz demonstrate how patterns of uneven regional development across Turkey reflect the country’s complex past.

In Turkey today, there continues to exist great regional variation in indicators of economic development. While the GDP per capita of Istanbul and Izmir is comparable with Belgium and Portugal respectively, regions such as Ordu or Diyarbakir compare more closely with the economies of Lebanon or Armenia. If one considers GDP in nominal terms, the disparities are greater still.

This phenomenon is well-known to economic historians of modern Turkey, with causes often ascribed to the structural characteristics of the Turkish economy, including its size and the asymmetrical allocation of financial resources. Yet this approach does not consider important micro-economic aspects, such as entrepreneurship, in its explanation.

Nor does it explain why variation appears to persist across time, with only modest changes in relative economic development during the period of the Republic. An historical, socio-spatial perspective might offer a useful additional explanation for this phenomenon, rooted in the upheaval of the transition from an Ottoman to a Turkish national economy.

Historical entrepreneurship in Anatolia

Like GDP per capita, rates of entrepreneurship in modern Turkey demonstrate considerable regional variation. According to entrepreneurship theory, GDP per capita informs entrepreneurship by regulating the availability of capital. But it can also work the other way. Places with higher ‘entrepreneurship capital’, defined as the social networks and cultural attitudes sustaining entrepreneurial activity, may be those more likely to generate prosperity.

Certain parts of Anatolia have historically been associated with high levels of commercialism, something which provides a starting point for this analysis. Ottoman Anatolia was largely rural, punctuated by dynamic market towns with historic ties to the Silk Route trade. Much of the Empire’s commercial and industrial activity concentrated in these and on its cosmopolitan port cities. The Late Ottoman Empire witnessed the apogee of the ‘Levantine’ port city. These ports formed a vital commercial bridge between Europe, Africa, central Asia, and the subcontinent. Constantinople (Istanbul), Smyrna (Izmir), and Trebizond (Trabzon) are names that carry a heady oriental lustre, redolent of a strident first age of globalisation, and of largely unfettered capitalism.

What differentiated both the Silk Route market towns and the Levantine ports from most of inland Anatolia was their large non-Muslim populations. Indeed, it was these which formed the engine of commercial activity, with Muslims traditionally prevented by their faith from conducting business. Throughout the last century of the Empire, wealth and prosperity flooded such centres, pumped in via international networks of diaspora Greeks, Armenians, and Jews. Despite the Empire’s Islamic core, Muslims were ‘second class’ in the economic sphere. This reality contributed to a sense of persecution, a feeling among Muslim Turks that the system was rigged against them.

Post-imperial trauma and Turkification

Early Republican economic thinking drew strongly from these sentiments, animated by a sense of ‘post-imperial trauma’. This provided the impulse for a lightning process of economic Turkification. Here, Republican cadres, such as the Unionists, pursued a ‘politics of reckoning’ with the past, though not necessarily a direct break. They deplored and sought to eradicate all foreign, non-Turkish elements, something achieved by deportations and extermination campaigns throughout 1914-1923.

Meanwhile, the state-builders envisaged transferring the activities of departing non-Muslims into Turkish hands, allowing daily economic life to continue and a national economy to emerge. Muslims were required to appropriate seamlessly the levers of economic power. The mechanism for this involved the mass transfer to Muslims of property, including many businesses, abandoned by outgoing Greeks and Armenians.

This process was neither easy nor automatic. That Muslims had represented only a thin under crust of the Ottoman commercial elite, often with little commercial background of their own, was a problem state builders would need to overcome. Republican policies thus sought to promote commerce and entrepreneurship among urban Muslims.

By engaging in commerce and enterprise, Turks would be serving the state and contributing to its national mission. The Turkish economy, they were told, could henceforth dance proudly to the clanging beat of the dockyards and factories of the industrial west. Meanwhile, Muslims were told they must inherit the objects, places, and identities which had hitherto been the preserve of non-Muslims. Such elements, they were taught, had always been ‘theirs’.

Varying local effects

This narrative was propagated across the country, though it concocted meanings depending on the local contexts it encountered. In the large cities of western Turkey and in the capital, Muslims were encouraged to adopt the trading and industrial activities previously held by Greeks, Armenians and Jews.

In Istanbul, epicentre of much nationalist enthusiasm, this involved seizing the engine room of the Anatolian and Black Sea economy with its heavily industrial character. Where industry continued to be controlled by large Greek and Jewish families, new Turkish entrants saw themselves as industrial ‘warriors of the nation’, hustling to put their predecessors out of business.

In Izmir, it meant assuming the identity of a place historically steeped in commerce and an economy based on exports. Nowhere else was there so large a redistribution of non-Muslim merchant property. Some 20,000 properties and land plots were re-assigned between 1923-1935. The occupation of places, such as the Kordon and the former Frank district, so redolent of Belle Époque Smyrna in its commercial heyday must surely have imbued in the newcomers a sense of themselves as the new merchant elite. Today ‘Izmirlis’, whether consciously or otherwise, see themselves as inheritors of a proud commercial tradition in the city. In both Istanbul and Izmir, such processes acted as lubricant for the continuation of earlier economic patterns and activities in the city, against a background of otherwise wholesale change.

A different process is evident in the rural Pontus. The Pontus was also home to large numbers of non-Muslims, mainly Greeks. Yet unlike in Istanbul and Izmir, these Greeks were poorer and engaged mainly in agriculture and fishing. There being no established tradition of trade and entrepreneurship, the incoming Muslims had no legacy to build on. Instead, they replaced the outgoing Greeks as farmers and fishermen.

Indeed, in much of the Anatolian interior, where historical populations of Jews and Muslims were smaller, the Kemalist doctrine of liberating places, activities, and identities held by foreigners had blunter teeth: in such places previously characterised by semi-feudal and barter-based economic systems, the absorption of western principles such as private enterprise has been slower and more superficial. In Malatya, for instance, where the non-Muslim population was small and where the economy for centuries relied on subsistence agriculture and carpet weaving, entrepreneurship remains low. Across much of Anatolia, this pattern repeats itself.

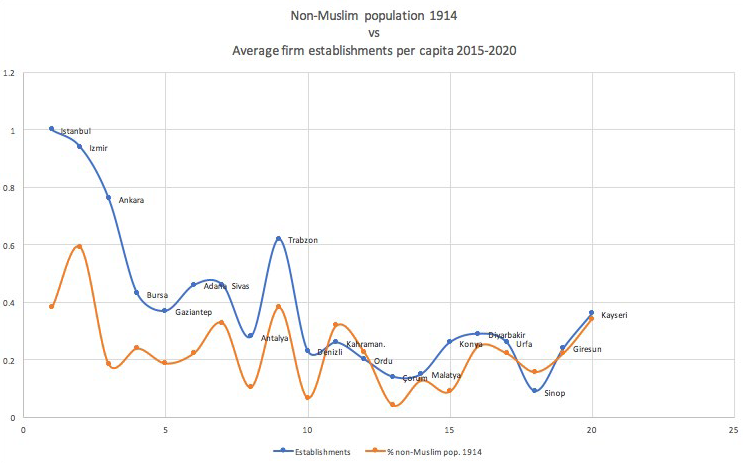

Figure: Start-up rates per region in 2015-20 versus non-Muslim populations in 1914

Note: Compiled by the authors.

It can thus be hypothesised that the local presence of significant non-Muslim commercial elites during the late Ottoman Empire is one, though by no means the only, useful predictor of regional entrepreneurship rates in Turkey today. The figure above demonstrates a strong correlation (0.73) between concentrations of non-Muslims in 1914 and present rates of entrepreneurship in major urban centres across Turkey.

Turkish entrepreneurship

Modern Turkey is a nation-state formed from the ashes of a multicultural empire. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire was violent and painful, while attempts to forge a national economy required the shedding of unwanted elements whilst assuming, and continuing, the economic functions these groups previously held.

These objectives were underpinned by a post-imperial ideology that assumed the victimhood of a Turkish people long subject to a ‘foreign’, ‘un-Turkish’ economic regime. Victimhood proved a powerful weapon for the legitimisation of several morally dubious acts. It is likely that forced deportations, followed by the appropriation and redistribution of property, permitted, in certain places, the relatively seamless continuation into the early Republic of activities and identities that were previously the preserve of non-Muslims.

Entrepreneurship, something earlier regarded with suspicion, was repurposed as a resolutely Turkish pursuit. Under the guise of a national economic doctrine, it became possible for new Turkish commercial elites to assume the culture and identity of the old in specific locales in which they operated. Places performing highly across indicators of entrepreneurship today appear to be associated with prosperous non-Muslim commercial elites in the late Ottoman period.

This finding tempts the academic lens back in time to address changing Muslim attitudes towards entrepreneurship and how these were affected both by Turkey’s post-imperial ideology and by the proximity to prosperous Christian and Jewish merchant elites. Indeed, it encourages a rethink of conventional approaches to modern Turkish economic development, which typically treats the years 1923 as an economic ‘ground zero’, downplaying the role of late Ottoman, and thus mainly non-Muslim patterns of economic activity, in informing the dynamics of the modern Turkish economy.

Pursuing this research avenue further should involve consideration of the micro-economic and social history of the period, considering individual stories of the early protagonists of the Turkish economy to enrich the broad narrative presented here.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: abdurahman iseini on Unsplash

Good basic review. The important element associated with Turkifying its economy, was financial and commercial links to Europe, Americas and Middle East that was missing. It has taken a hundred years to learn and establish such channels.